One simple well‑lit white cube gallery space within the public library premises of Byron Bay, in range of a favourite coffee shop, is Lone Goat Gallery. It’s the setting for exhibitions by local artists or groups managed by a dedicated curator and a committee of volunteers, which was catapulted into another sphere during April 2024. The artist is indeed local, but the project was no less than a history of Australian First Nations dispossession and some of the ragged whitefella attempts to ameliorate the devastating effects of colonisation on an ancient culture. In play are high‑end professional skills in photography, graphics, Photoshop and exhibition design all in the skilful and inspired hands of an artist who is also an historian, communicator and writer—with a lifetime of observation and action behind him. David Morgan is this polymath. Here the tools of photographic imagery plus historical documents have been stretched, pulled apart and recombined to reveal threads and ligaments of human minds and bodies that become the fabric of connections between two cultures: one ancient, one modern, and each very differently constructed.

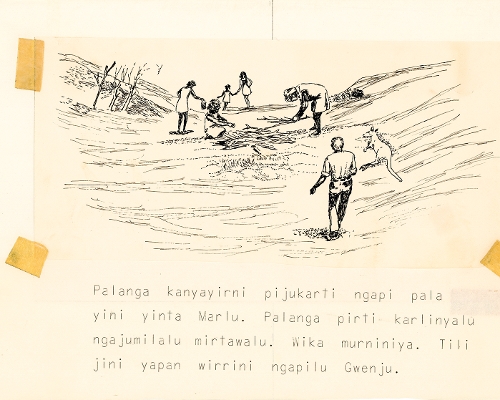

The life of Morgan is one of the pivots around which Unfinished Business spins. Morgan was born to the daughter of an early 20th century British settler farmer in dry western NSW. Educated in Melbourne in the 1960s, he developed a thirst to understand how such radically different cultures might co‑exist. Fine art and graphic design studies at Caulfield and a five‑year stint at the National Museum of Victoria gave way to hitching to the Northern Territory where he got work in the early bilingual literacy programs in Milingimbi/ Yurruwi, a small island community off the northern coast of Arnhem Land. As one of the resilient and talented whitefellas first employed in the Top End and the Pilbara in Western Australia, he witnessed first‑hand and across the decades the devastating impact of various church and government policies. Having always been a photographer he decided to explore other media after he settled in Bundjalung country, northern NSW in 2000.

Traversing the eleven different and distinct but linked zones of pictorial/ narrative devices in the gallery keeps the viewer alert, beginning with the orientation of place: first we see large luscious full‑colour aerial views of the Bundjalung coast beautifully photoshopped over with original ‘big scrub’ vegetation and the cultural objects of its traditional Indigenous owners. Adjacent to this is a detailed patchworked historical map, overlaid with images of a curious chain‑with‑ handle item which turns out to be the tool used by early surveyors. In seeking the logic or meaning of this complex work, the visitor looks long and hard, and looks again and again.

The artist’s stated impetus for Unfinished Business was the urgent need, personally and deeply felt, for truth telling in the wake of the defeat of the Voice to Parliament in the 2023 referendum. The story told in this collection of works is of one white family, and their lives across more than 150 years. It begins when Morgan’s grandfather arrived on a ship, and it is visually punctuated by the racist markers of ethnographic theories and government interventions as the decades ricochet up to today. An image of the artist’s father digitally inserted walking alongside the execrable Chief Protector of Aborigines, AO Neville; the spectral image of A.P Elkin, Anglican clergyman, anthropologist and doyen of the assimilation policy also manifests. And now, with the Voice silenced by politicians and an ill‑informed voting population, it seems that nothing much has changed.

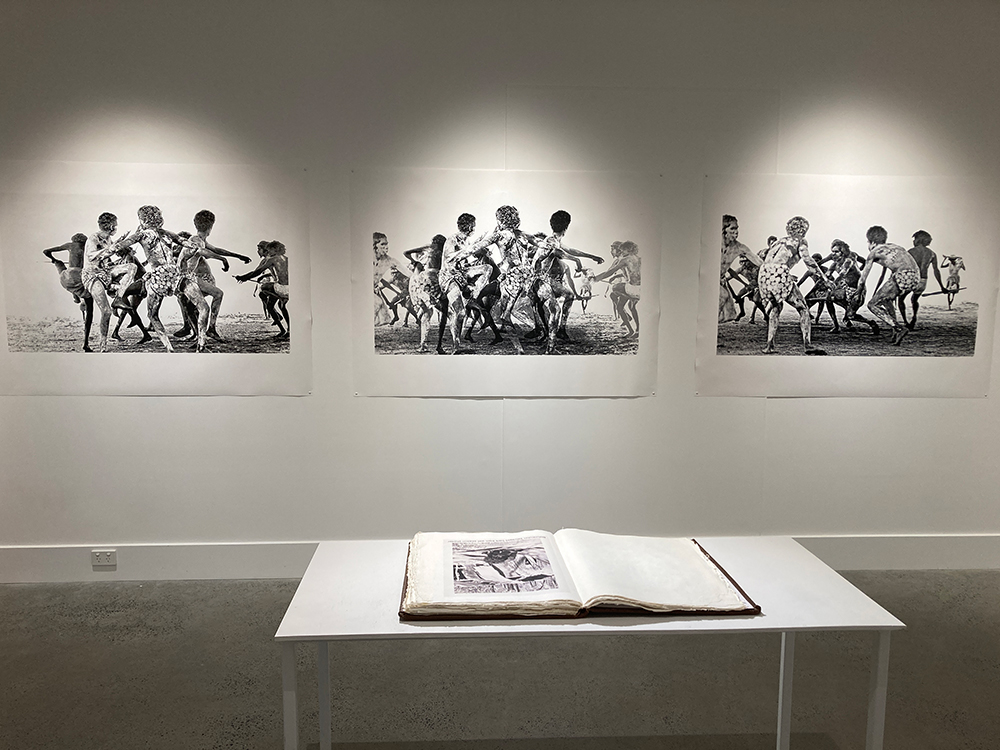

Some of this fifty‑year panoply of witnessing emerges within vintage op‑shop items. The title on the first page of a weighty, heavily tooled wood‑bound Engagement Album is Statement from a Wounded Heart (2024), a series of low‑resolution images taken from the media, showing players during the chaos of the Voice campaign in murky, indistinct registers. A large old wooden pencil box/case, as used in 1950s primary schools, is a frame for a landscape with one surviving tree; an elegant drawing room curiosity houses a horizontal scroll that the user can wind back and forth using two little brass handles, but instead of the Swiss Alps we see an extensive series of sepia‑toned historical images from the region and its maps, always the maps.

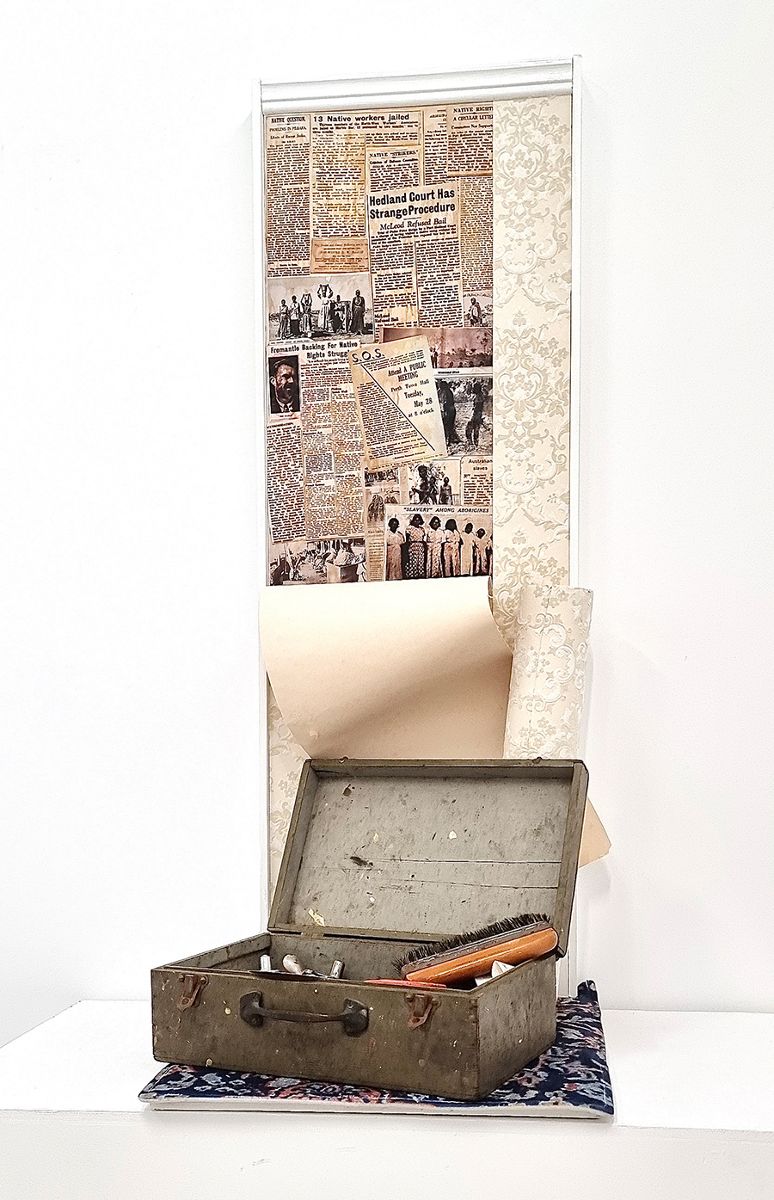

Next we find a framed box assemblage caught in the act of wallpapering over troublesome newspaper stories, old glue‑brush in a box ready to cover up the inconvenient truths. Nearby is an intense photograph of a white man standing in the wind in tattered shorts, an asbestos miner born in 1908 who became a key player in the historic 1946 Indigenous walk‑off from what was effectively serfdom in the Pilbara—two decades before the more famous Gurindji/Wave Hill walk off. Who was Don McLeod? He may or may not be in school textbooks but a university research centre in the USA has created a blow‑by‑blow study of the whole event including McLeod’s conviction and imprisonment for his role in the Aboriginal self‑determination struggle and his membership of the Australian Communist Party.

Already the viewer is reeling with the complexity. We are accustomed to moving around a gallery at a steady pace, stopping from time to time, reading the labels, taking a few photos, and moving on to other pursuits. So what is this? Is it an archival museum exhibit? If so, where are the white gloves, the dim lighting and the chairs? How is it we can touch and interact with what at first sight appear to be precious original historical items? I went back three times, and each time the layering and complexity revealed more… and more of our interwoven history.

Who would have thought that a digitised concertina book could hold such powerful content? The form emerges as a mode to portably encapsulate a huge wealth of detail, imagery and ideas, in three highly readable ‘chapters’ as in three symphony movements, mounted on three shelves. At the top is A Matter of Policy (2022), showing politicians and officials in plain greys and white; in the middle is the artist’s own extensive family history, predominantly sepia or black, with intimate detail from many viewpoints about issues of the time (c. 1900‑1950).

The third concertina hints at a visual conversation between Morgan and Kim Mahood, another artist and desert dweller, more widely known as a groundbreaking writer on the cross‑cultural interface between Aboriginal and white Australia. It shows Morgan’s exquisite Google earth photo‑work responses to country, interspersed with art works by Mahood in which she attempts to create her own visual language of the desert that acknowledges the existence of preexisting Indigenous world views. In the centre, a dramatic white clay face portrait of Mahood by the late photographer Pamela Lofts who, like Mahood, was raised in the territory, leaps off the wall.

The genius of this multi‑focused exhibition, with its carefully established cultural permissions and conversations, is its breathtaking ambition: to speak at multiple levels to visitors to a small regional gallery, whether long time locals or tourists. Its humble intention is to stretch the viewers’ minds and emotions, and to grapple with the country and nation and world we inhabit here and now.

Unfinished Business needs to be acquired by a public institution and toured throughout Australia. It all fits into a couple of cardboard boxes, for now repacked and stored in the artist’s rural home.

_Card.jpg)