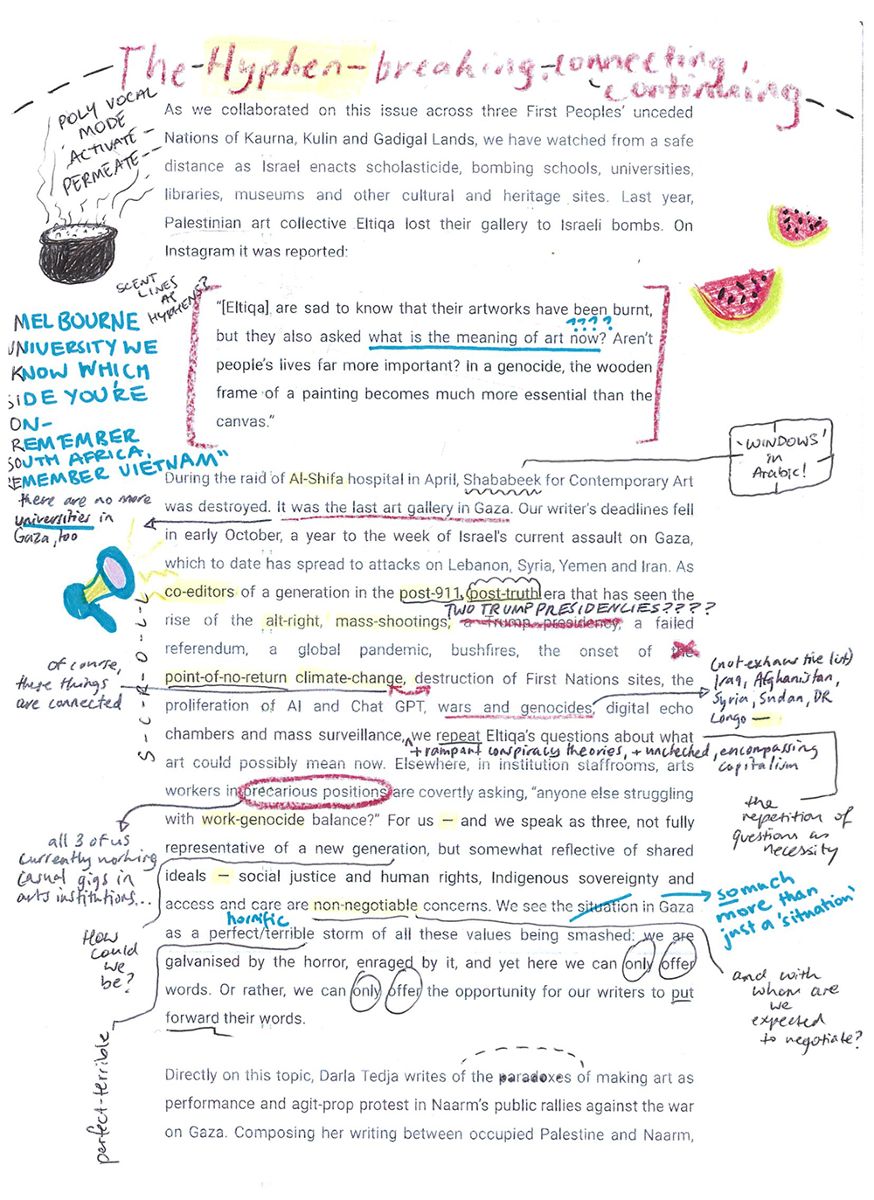

As we collaborated on this issue across three First Peoples’ unceded Nations of Kaurna, Kulin and Gadigal Lands, we watched from a safe distance as Israel enacted scholasticide, bombing schools, universities, libraries, museums and other cultural and heritage sites. Last year, Palestinian youth art collective Eltiqa lost their gallery to Israeli bombs. On Instagram, it was reported:

[Eltiqa] are sad to know that their artworks have been burnt, but they also asked what is the meaning of art now? Aren’t people’s lives far more important? In a genocide, the wooden frame of a painting becomes much more essential than the canvas.[1]

During the siege of Al-Shifa Hospital in March, Shababeek for Contemporary Art was destroyed. It was the last visual arts centre in Gaza.[2] Our writer’s deadlines fell in early October, a year to the week of the Hamas attack on Israel and Israel's current assault on Gaza, which to date has spread to attacks on Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and Iran. As co-editors of a generation living in a post-911, post-truth era—that has seen the rise of the alt-right, mass-shootings, two Trump presidencies, a failed Australian referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament, a global pandemic, bushfires and floods, the onset of the point-of-no-return climate-change, destruction of First Nations sacred sites, the proliferation of AI and ChatGPT, wars and genocides, digital echo chambers and mass surveillance—we repeat Eltiqa’s question on what art could possibly mean now.

For us—we speak as three, not fully representative of a new generation, but somewhat reflective of shared ideals—social justice and human rights, Indigenous sovereignty, access and care are non-negotiable concerns. We see the “situation” in Gaza as a perfect/terrible storm of these values being smashed: we are galvanised by the horror, enraged by it, and yet here we can only offer words. Or rather, we can only offer the opportunity for our writers to put forward their words.

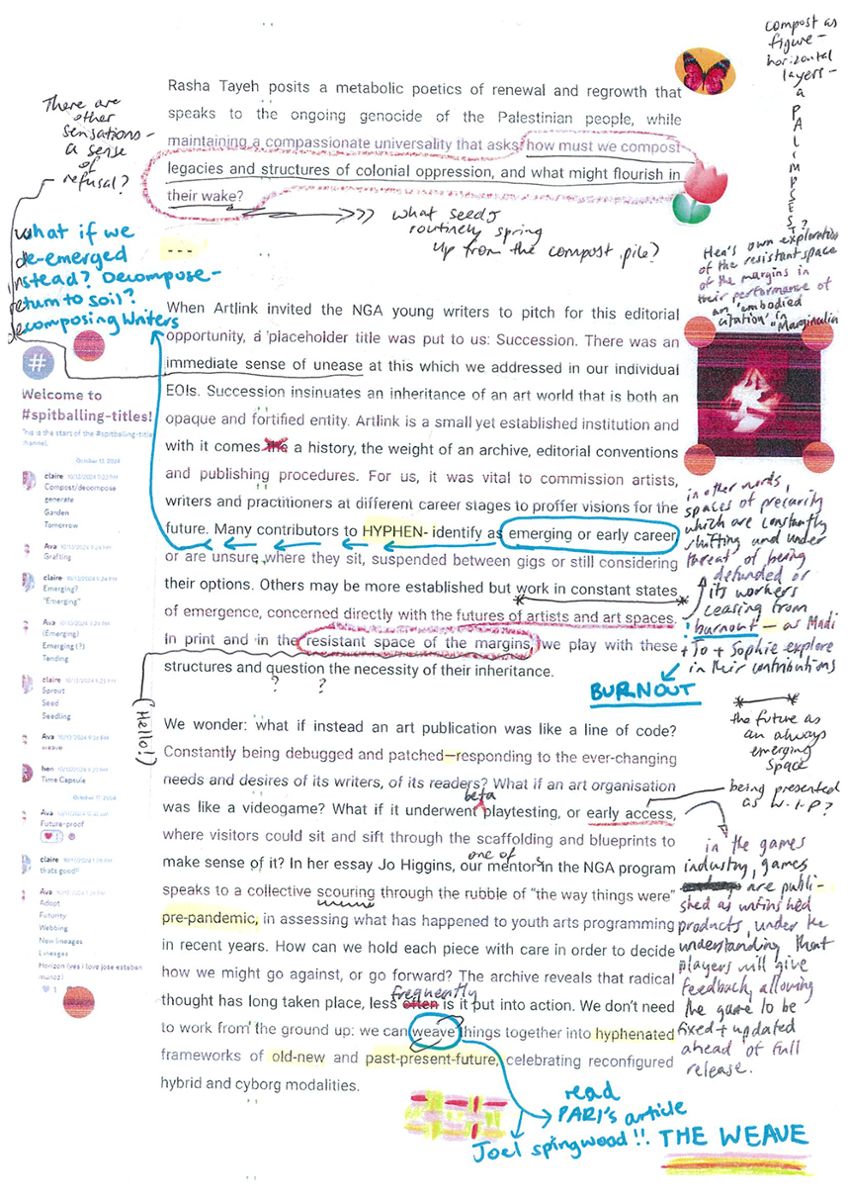

Directly on this topic, Darla Tejada writes about the paradoxes of art as performance and agit-prop protest in Naarm’s public rallies against the war on Gaza. Composing her writing between occupied Palestine and Naarm, Rasha Tayeh posits a metabolic poetics of renewal and regrowth that speaks to the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people, while maintaining a compassionate universality that asks: how must we compost legacies and structures of colonial oppression, and what might flourish in their wake?

When Artlink invited the alumni of the NGA’s National Young Writers Program to pitch for this guest editorial opportunity, a placeholder title was put to us: Succession. Our cohort rejected this premise, which we addressed in our individual expressions of interest. As a term, succession insinuates an art world that has been naturalised as an opaque and fortified entity, which we simply inherit — for better and worse. Artlink is a small yet established institution and with it comes a history, the weight of an archive, editorial conventions and publishing procedures. As guest editors, it was vital we commission artists, writers and practitioners at different career stages to proffer visions for the future. Many contributors to Hyphen identify as emerging or early career, or are unsure where they sit, suspended between gigs or still considering their options. Others are more established but work in constant states of emergence, concerned directly with the futures of artists and art spaces. In print and in the resistant space of the margins, we play with these structures and question the necessity of their inheritance.

In her essay, Jo Higgins—coordinator of the NGA program and one of our mentors—speaks to the same intergenerational concerns. She scours the rubble of ‘the way things were’ pre-pandemic, in assessing what has happened to youth arts programming in recent years. We similarly propose alternative models: what if an art publication was like a line of code? Constantly being debugged and patched. What if it responded to the ever-changing needs and desires of its writers, of its readers? What if an art organisation was like a videogame? What if it underwent playtesting, or early access, where visitors could sit and sift through the scaffolding and blueprints, or peek behind the code— the “crawlspace”—as Sophie Penkethman-Young describes in her piece on online Australian ARIs.

As guest editors, how can we hold the words of our writers with care, to decide how we might go against the past or go forward into the future? The Artlink archive reveals that radical thought has long taken place, less often is it put into action. We don’t need to work from the ground up: we can weave things together into hyphenated frameworks of old-new and past-present-future, celebrating reconfigured hybrid and cyborg modalities.

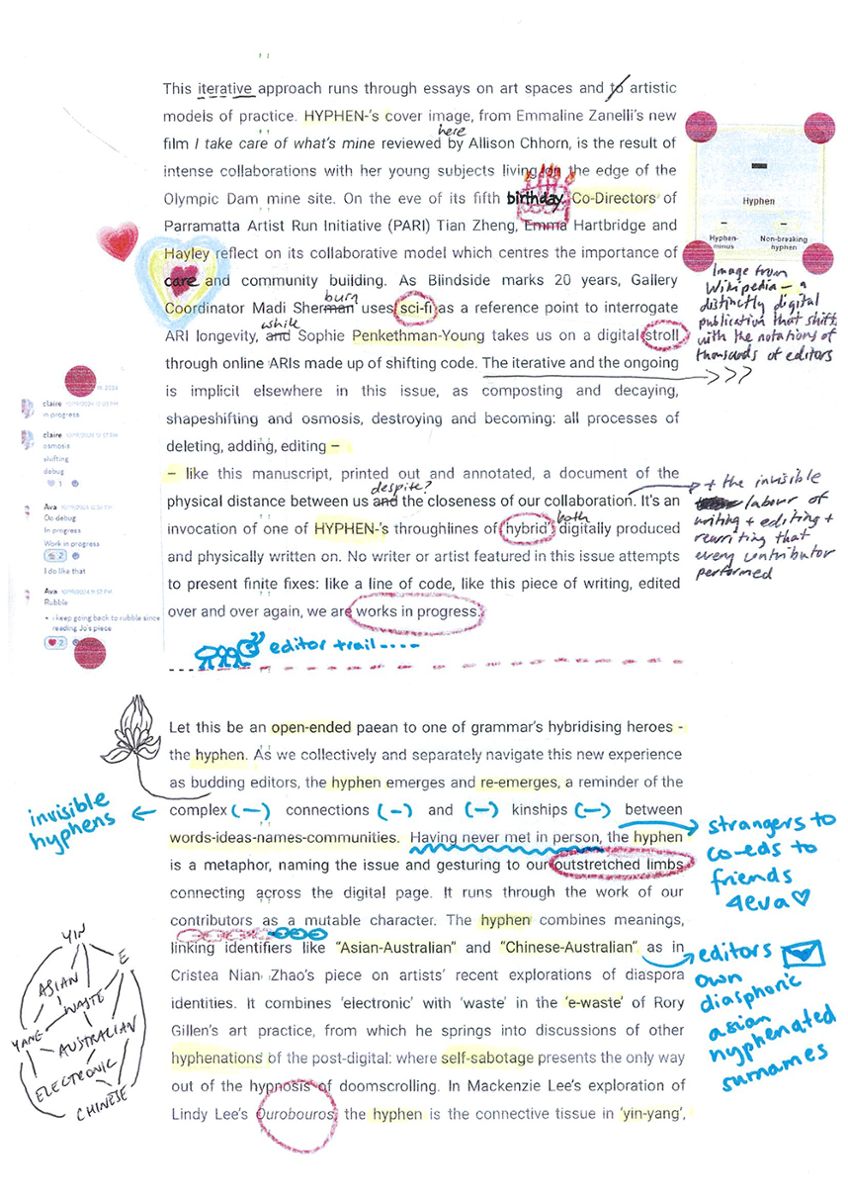

This iterative approach runs through essays on art spaces and artistic models of practice. Hyphen’s cover image, a still from Emmaline Zanelli’s new film, I take care of what’s mine (2023–24), reviewed by Allison Chhorn, is the result of intense collaboration with her young subjects living on the edge of the Olympic Dam mine site. Likewise, salvaged debris from the decommissioned Warrego mine, on Warumungu Country, is treated with alchemical mastery in Lisa Slade’s review of Tennant Creek Brio: Juparnta Ngattu Minjinypa Iconocrisis. On the eve of its fifth birthday, co-directors of Parramatta Artist Run Initiative (Pari) Tian Zhang, Em Harbridge and Hayley Coghlan reflect on its collaborative model, centred on care and community building. And, as Blindside marks 20 years, gallery coordinator Madeleine Sherburn uses sci-fi as a reference point to interrogate ARI longevity. Iteration and the enduring revisionism are implicit elsewhere in our issue: shapeshifting and osmosis, destroying and becoming, processes of deleting, adding, editing — like this manuscript, printed out and annotated, a document of the physical distance between us and the closeness of our collaboration. Our editorial is an invocation of one of Hyphen’s ‘hybrid’ throughlines: digitally produced yet physically marked up. No writer or artist featured in this issue attempts to present finite fixes. Like a line of code, like this piece of writing, edited over and over, we are works in progress.

Let this issue be an open-ended paean to one of grammar’s hybridising heroes—the hyphen. As we collectively and separately navigate this new experience as budding editors, the hyphen emerges and re-emerges, a reminder of the complex connections and kinships between words-ideas-names-communities. Having never met in person, the hyphen is a metaphor, naming the issue and gesturing to our outstretched limbs connecting across the digital page. It runs through the work of our contributors as a mutable character. The hyphen combines meanings, linking identifiers such as “Asian-Australian” and “Chinese-Australian”, as in Cristea Nian Zhao’s piece on artists’ recent explorations of diaspora identities. The hyphen combines ‘electronic’ with ‘waste’ in the ‘e-waste’ of Rory Gillen’s art practice, from which he springs into discussions of other hyphenations in the post-digital world. In Mackenzie Lee’s exploration of Lindy Lee’s Ouroboros (2021-24), the hyphen is the connective tissue in the ‘yin-yang’ that binds opposites together — a perpetual yet balanced cycle. The hyphen is the go-between, mediating sides of a binary or, better yet, the thread that pierces words to create a line of code — a horizontal figure for possibilities on the page, across the web and in the world.

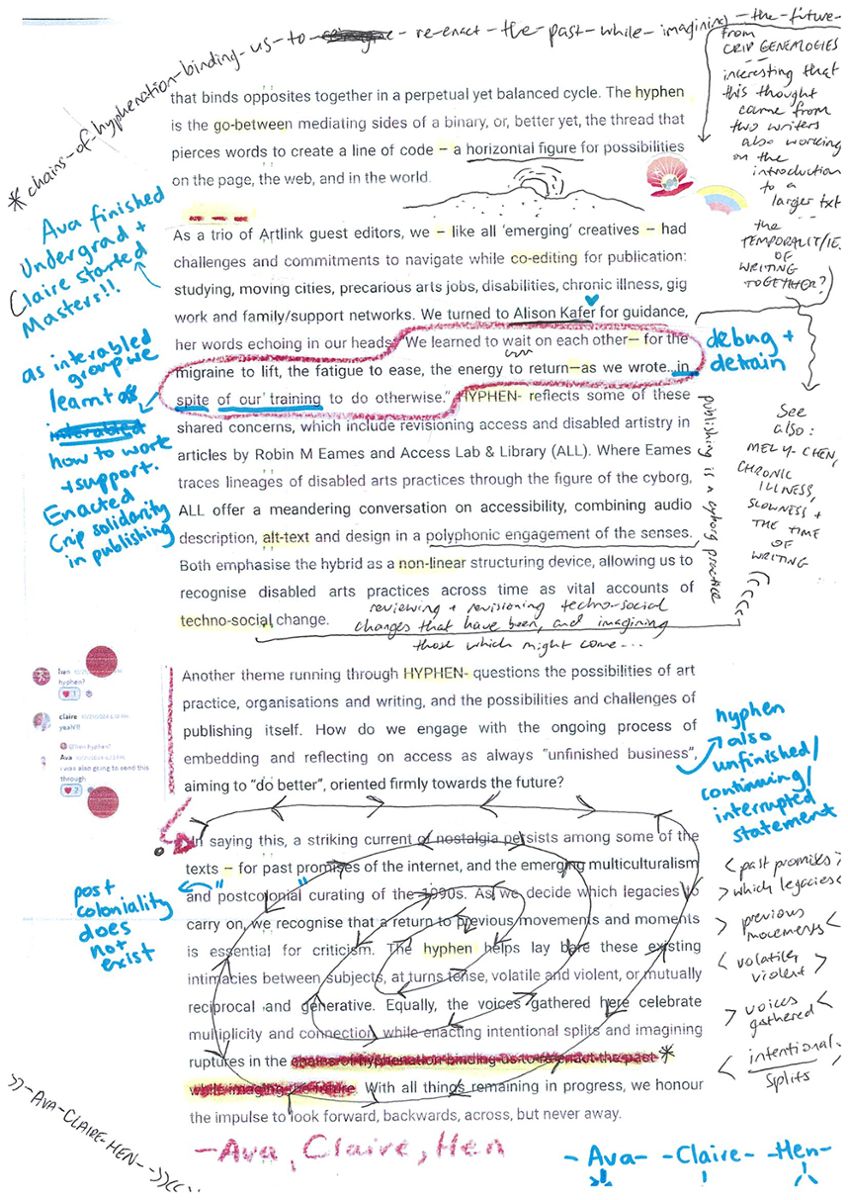

As a trio of first-time Artlink guest editors, we—like all ‘emerging’ creatives—navigated challenges and commitments while co-editing our issue: studying, moving cities, precarious arts jobs, disabilities, chronic illness, gig work and family/support networks. We turned to the words of American academic Alison Kafer for guidance: ‘We learned to wait on each other—for the migraine to lift, the fatigue to ease, the energy to return—as we wrote…in spite of our training to do otherwise.’[3] Hyphen reflects some of these shared concerns, which includes revisioning access and disabled artistry in articles by Robin M Eames and Access Lab & Library (ALL). Where Eames traces lineages of disabled arts practices through the figure of the cyborg, ALL offer a meandering conversation on accessibility, combining audio description, alt-text and design in a polyphonic engagement of the senses. Both emphasise the hybrid as a non-linear structural device, allowing us to recognise disabled arts practices across time as vital accounts of techno-social change.

Another theme running through Hyphen is questioning the possibilities of art practice, organisations and writing, the possibilities and challenges of publishing itself. How do we engage with the ongoing process of embedding and reflecting on access as always “unfinished business”, aiming to “do better”, oriented firmly towards the future?

In saying this, a striking current of nostalgia persists among some of the texts, like the past promises of the internet or a look back on the emerging multiculturalism and postcolonial curating of the 1990s. As we decide which legacies to carry on, we recognise that a return to previous movements and moments is essential to criticism. The hyphen helps lay bare these existing intimacies between subjects, at turns tense, volatile and violent, or mutually reciprocal and generative. Equally, the voices gathered here celebrate multiplicity and connection, while enacting intentional splits and imagining ruptures in the chains-of-hyphenation-binding-us-to-re-enact-the-past-while-imaging-the-future. With all things remaining in progress, we honour the impulse to look forward, backwards, across, but never away.

Footnotes

- ^ Question of Funding, Instagram @the_qof_collective, 21 December 2023. See also: Rhea Nayyar, “Gaza art gallery reportedly destroyed by Israeli airstrike”, Hyperallergic, 21 December 2023

- ^ Sarah Kuta, “Arts Center in Gaza Destroyed in Israeli Hospital Siege,” Smithsonian Magazine, 12 April 2024

- ^ Alison Kafer, “Manifesting Manifestos” in Crip Authorship: Disability as Method, ed. Mara Mills and Rebecca Sanchez (New York: New York University Press, 2023), 186