Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Anthropocene ...

Contributors

Issues

Articles

It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

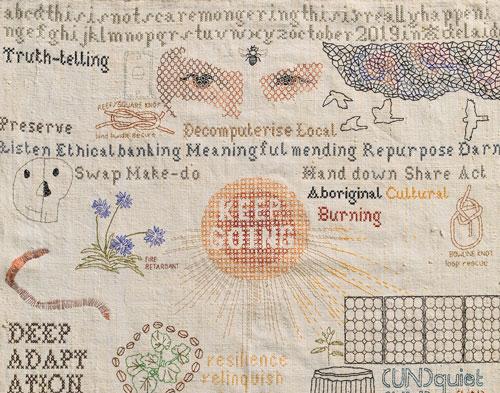

Sometime on from this provocative trueism attributed to Fredric Jameson or Slavoj Žižek, attempting to capture the momentum of the climate crisis and an associated distrust of the ability of governing bodies to tackle the systemic imbalances has proved to be a growth industry for die-hard aesthetes. This is the new normal, a contagious meme, signalling the putative end times.

As Samuel Johnson said to Boswell, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

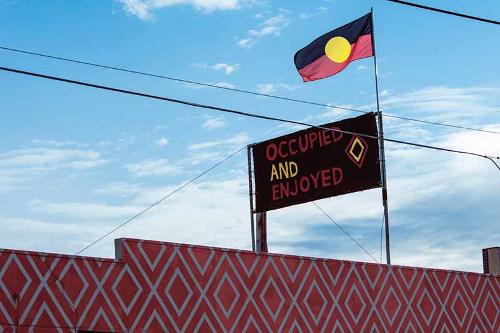

I thought of this definitive comment on time as I was writing this article in late December 2019 in the Blue Mountains, in forty degrees temperatures as smoke swirled around outside from fire storms only kilometres away. We had been told to evacuate but we didn’t, we’d been through this before. The car was loaded up, the cats locked in the house and their cages ready to pack and run. But immanent immolation did not concentrate my mind, or only in the wrong way as I compulsively checked FiresNearMe and messaged friends to check they were okay. They often weren’t: several were burnt out, many had life-threatening escapes, and evacuations were commonplace. My friend Ronnie Ayliffe was posting videos of burning trees falling onto the road as she fled her farm and headed for Cobargo, itself already on fire.

Sometimes the truth is impossible to hear. At year’s end, dinner table conversation turns from climate change to mass extinctions, and people consult their pocket encyclopaedias for facts. Someone asks: “Exactly how many birds in Aotearoa have gone extinct?” Even Wikipedia claims an incomplete list. In Te Ara ecologist Richard Holdaway tells the numbers more clearly: 50% of vertebrate fauna gone in the 750 years since human arrival in New Zealand. Numbers overwhelm in Australia too. Here, humans have been living amidst other animal species for tens of thousands rather than hundreds of years, and the list of extinctions add to our dinner table litany.

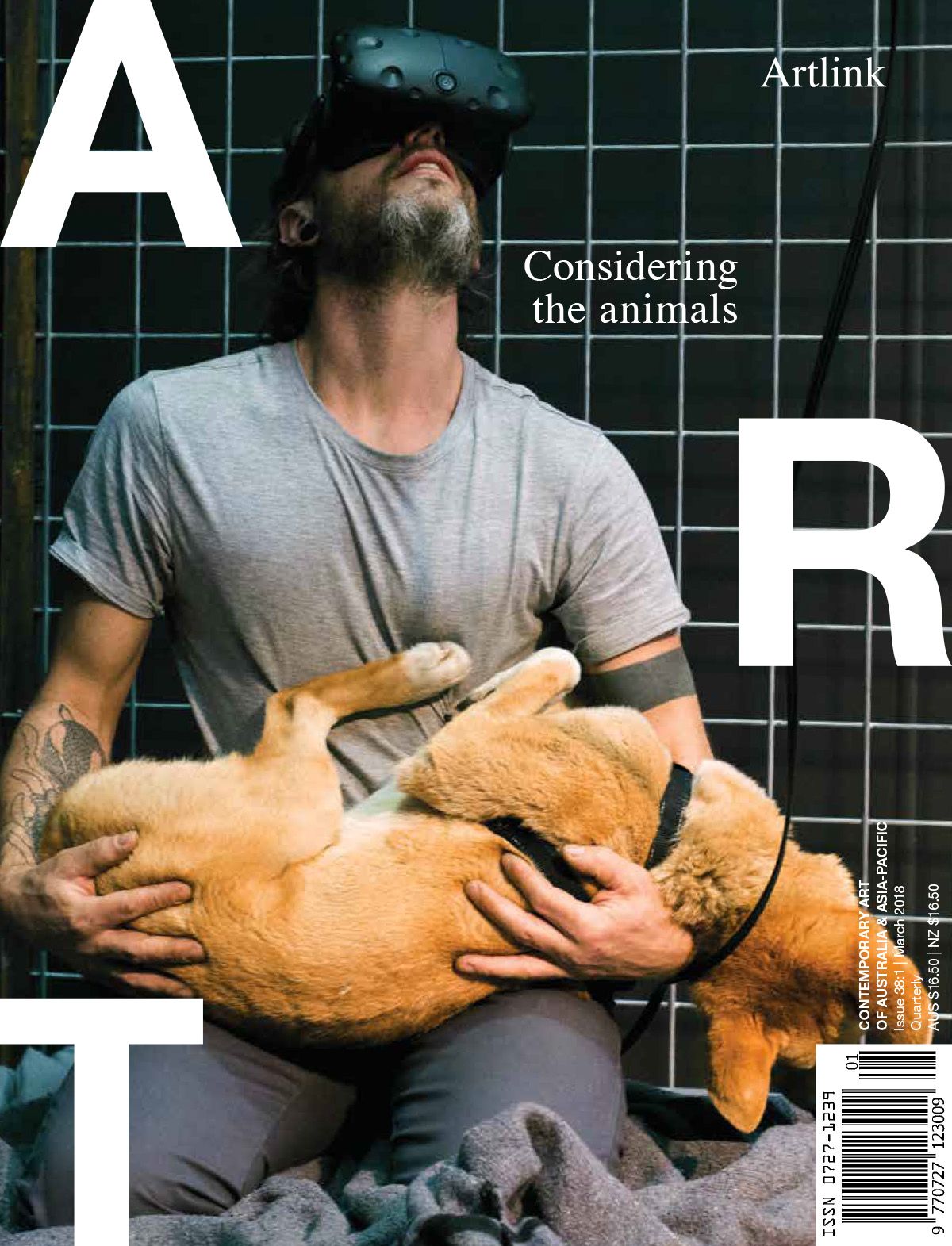

Four humanimals creep, crawl, sniff and moan their way through a seated audience, towards an empty performance area which awaits their presence. Snorting and snuffling is audible as the liminal creatures rub themselves against giggling audience members, rolling across laps and crawling under chairs. Their faces are painted with dark bands across the eyes—like a species of bird, bandit, or warrior. When they reach the performance area, they crouch in a circle, continuing their muffled cries as one of them stands.

From the early 1970s, driven by drought and degradation of interior wetlands, the Australian White Ibis (Threskiornis moluccus) began migrating to the nation’s coastal cities, towns and inland centres from north Queensland through to Perth. Ibis have flourished in urban spaces, where there is a ready food supply guaranteed by our endemic over‑consumption. Their robust colonisation and presence has garnered the bird a reputation as unwelcome pests and interlopers, reflected in the quotidian idiom: dumpster diver, flying rat, tip turkey, pest of the sky, trash vulture, dump chook, bin chicken, bin chook.

“I don’t know” sings the chorus in response as Madison Bycroft rallies off quip after quip the characteristics of a mollusc life-world while occupying a mollusc-like dress at the back of the mollusc-like stage. What this lecture-performance Soft Bodies (2017) addresses is a problem that faces much of the arts and humanities in the twenty-first century: a grappling with the ontological becomings and tentacular thinking, of those things that are and are not us. As science continues to illuminate the molecules and viruses that make up our bodies, we are plunged into a world where ideas about what distinguishes us as humans (and our understanding of what a human is) have become increasingly vague. As environmental philosopher Timothy Morton avows in solidarity, we are more non‑human than we are human. So what happens when boundaries that previously demarcated one thing from another disintegrate? And what do molluscs have to do with it?

Theories are living and breathing reconfigurings of the world.

Karen Barad, from “On Touching—The Inhuman that Therefore I am.”

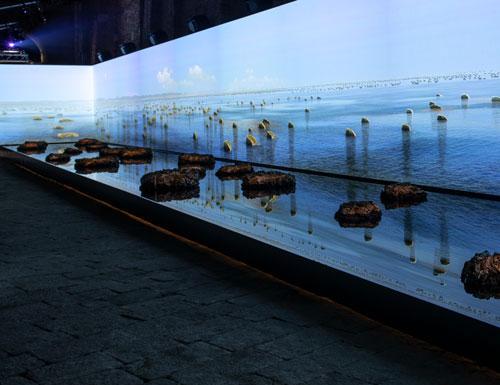

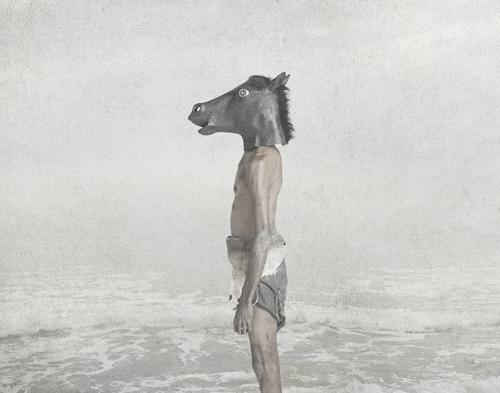

Contemporary animal theory confronts some of the most profound issues of our time—what it means to be human in the Anthropocene, anthropocentrism and the mass extinction of species, the rights of nonhuman animals and the future of ethical thinking. Artists, writers and filmmakers explore these and related issues in works that are experimental and challenging, testifying to this time of crisis. These include Michael Cook’s human–nature studies (Civilised, 2012; Invasion, 2017), Janet Laurence’s work on extinction (After Eden, 2012), Patricia Piccinini’s exploration of the posthuman (Evolution, 2009), Sue Coe’s bearing witness to slaughterhouses (Dead Meat, 1996; Porkopolis, 2001), J.M. Coetzee’s writings on animals and ethics (Elizabeth Costello, 2003, Disgrace, 1999) and Nicolas Philibert’s indictment of zoos in his documentary, (Nénette, 2010).

Vivid and arresting paintings of Australian wildlife are the hallmark of an artist known mononymously as Turbo. Born Trevor Brown (1967–2017) in Mildura, he took up painting in his mid‑thirties after he had relocated to Melbourne. He rapidly gained critical and commercial attention for works using a quick and direct application of pure colour, bursting with raw energy, and featuring a varied cast of native fauna. So exclusive—obsessive, even—was his portrayal of animals that there arose a kind of origin story explaining his single‑mindedness: “Uncle Herb [P]atten, the man he loves as a father, once asked Brown why he only painted animals. He replied that when he was fifteen and living on the Mildura streets and the Murray River bank, the animals were his only friends.” Other explanations Turbo gave for his choice of subject matter included, “Animals are my friends. They come to me in my dreams” and “When I paint, I feel like I’m in the Dreamtime and can see all the animals that live there.”