Search

You searched for articles ...

Some things won’t change, a woman told me in a small room on Bundjalung Country, filled with other women weaving; the smell of raffia and pillows. It was raining so we couldn’t sit outside. I began to weave a circle.

We thought we trusted the bush to be there, but then fire comes, Ruth said. We thought we could turn to the river, but then it overflows. The places we take refuge don’t feel so safe. But we can count on galaxies and bacteria and stones to be around long after we are gone.

Driving my carbon-belching hatchback from one colonial settlement to another, I listened to a book about microbes under a slivered moon. Fires flanked me at one point on the road. They weren’t close enough to scare, contained, but there: the contents of my gut, and the flames.

To continue reading…

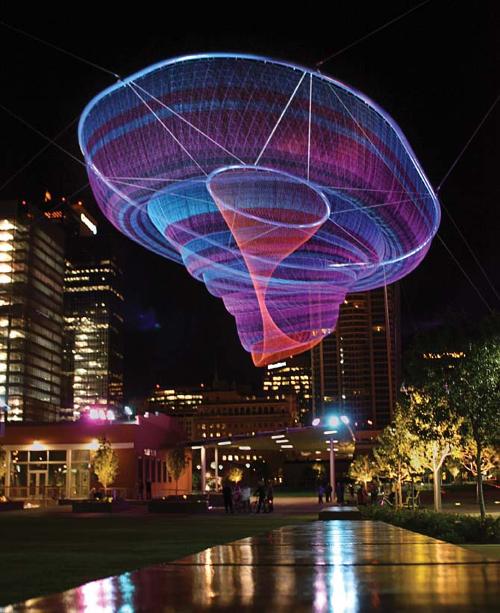

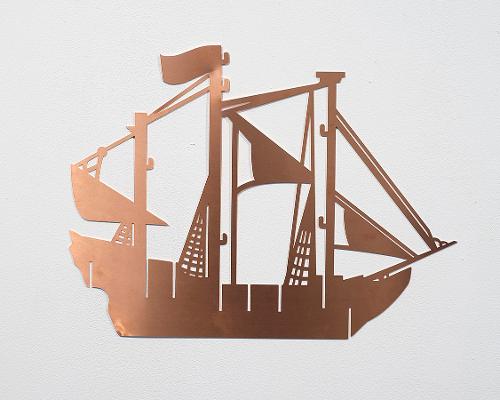

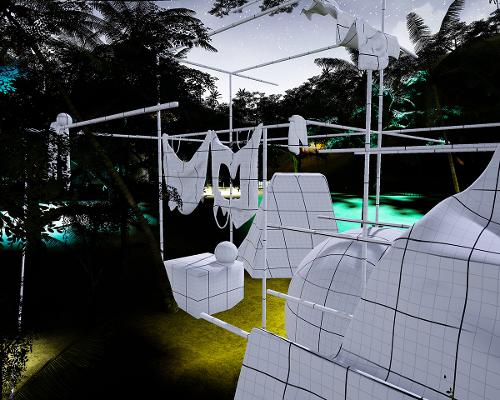

The art-raft project is, in Hakim Bey / Peter Lamborn Wilson’s words, a materialised ‘temporary autonomous zone’, where collaborators and activists have space to playfully propose questions, be involved in a common cause, generate connection and envision more positive future narratives.

The project began as a response to the needs of the People’s Blockade, a peaceful ‘flotilla’ protest organised by Rising Tide, held annually in the harbour and river mouth of the Coquun/ Hunter River, at Muloobinba/Newcastle. United on Awabakal and Worimi land and waters, the November 2023 protest saw 3,000 people occupying the world’s largest coal port for 34 hours.

To continue reading…

South Australian creative duo Laura Wills and Will Cheesman are the artists we need for the future. Partners in life and work, the pair have collaborated informally for nearly two decades, since the mid-2000s. Working across public art, relational and participatory practices, the duo—formalised as Wills Projects in 2020—invite many hands to co-create and deliver their projects, promoting non‑hierarchical structures of engagement that cater to the capacity and diversity of their participants. Based in Tarntanya / Adelaide, on Kaurna Yarta, Wills Projects is an exploration of the artists’ action-oriented yet reflective way of responding to the world. Prior to meeting, the pair lived parallel lives, riding bikes around Australia, living in squats in Europe, volunteering and WWOOFing, all while creating art. These experiences brought them together in what Wills refers to as ‘a shared culture’.

To continue reading...

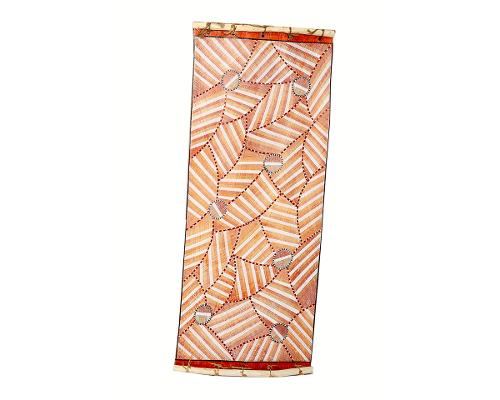

decolonial poetics (avant gubba) (2017), by Bundjalung poet Evelyn Araluen, captures a poignant facet of Katie West’s practice: ‘there are no metaphors here’ [poet’s spacing]. Amid the turbulent aestheticisation of changing climates, biodiversity, colonial legacies and land management, Araluen cautions us to ‘…not touch the de’ [poet’s emphasis]. The rapid adoption of “eco-critical” and “post”-colonial curation, making, staging and writing, in recent times, manifests in work that leaves us with an ecological feeling, a subtle gesture or zephyr. The process of decolonisation, however, cannot simply linger in the air, resting in the conceptual world. Nor can the “eco‑critical”. There is little room for the metaphorical rendering of these material challenges. The relationship between anticolonial projects and environmental consciousness is pervasive, and the health of Country mirrors the health of peoples. The theft and degradation of land always follows in colonialism’s footsteps: Violence inscribed upon the land is inscribed in both minds and bodies.

To continue reading...

In addition to the well-known effects of climate change—melting ice caps and rising sea levels, the increasing frequency of natural disasters, drought and dangerous heat—there are more subtle, psychological affects: feelings of anxiety or dread while thinking about the future, exhaustion and fatigue when reading news stories about the climate emergency, or a churning stomach when trying to come to terms with our limited agency in the face of this capitalism-induced climate crisis.

To continue reading...

Leading up to the first sculpture exhibition held in the grounds of Hans Heysen’s 132-acre property, The Cedars, in March 2000, the area around the shady pool, the site of one of Heysen’s iconic paintings, had slowly been cleared of the head-high broom that covered much of the estate. The back-breaking working of cutting and swabbing the weeds was undertaken by a group of volunteers headed by environmentalists Trevor Curnow and his partner Helen Lyons as the group Trees Please! (an offshoot of Trees for Life), established in 1998 to support the preservation and regeneration of the remnant bush at The Cedars. The late Helen Lyons was a local Hahndorf artist, and her connection with The Cedars landscape inspired her idea of holding an exhibition of installation-based artworks in the vicinity of the shady pool. She had previously founded The Artist’s Voice collective in 1997 and had artists ready and willing to be involved in the venture. The Artist’s Voice members exhibited regularly at the Hahndorf Academy’s upstairs gallery, but some members were open to Lyons’ vision for a non-commercial, experimental exhibition at The Cedars focused on environmental principles. The Cedars’ long-term curator, Allan Campbell was also supportive, and Lyons invited the twelve participating artists to make works in direct response to the landscape, making use of materials found on the property. This inaugural exhibition, A Homage to Nature was the first of many, now known collectively as the Heysen Sculpture Biennial, a series which can be considered a visceral response to the environmental art movement that emerged globally in the 1960s.

To continue reading...

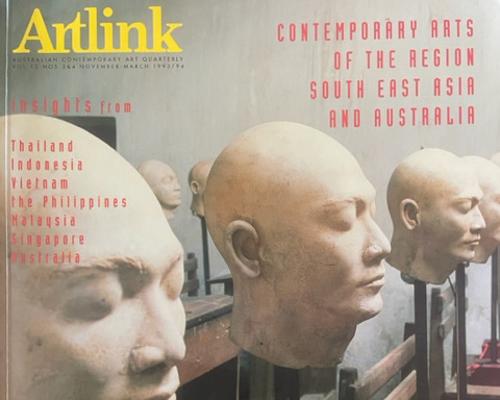

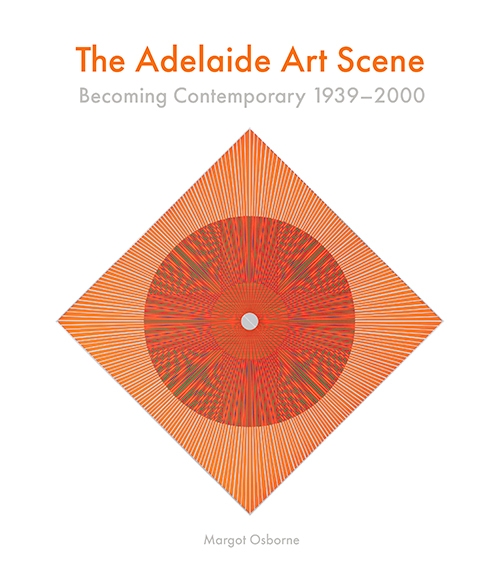

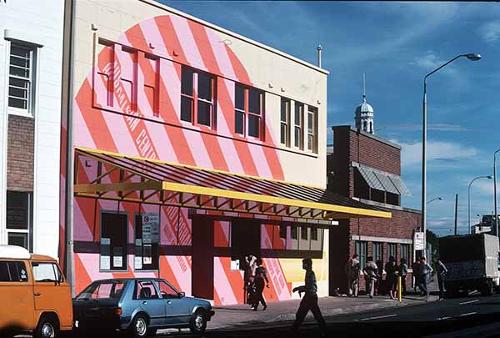

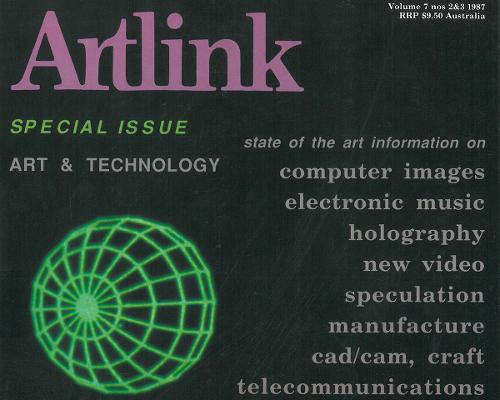

Bernard Smith's assertion in 1943, that it is "truly absurd nowadays to talk of 'modern art' as a single entity," encapsulates a sentiment that has persisted through the decades and finds resonance in Margot Osborne's exploration of Adelaide's art scene. Osborne's work, a solidly researched and expansive history, with re-printed archival material and an extensive index forming a doorstop omnibus which chronicles the critical historical events and figures who have shaped Adelaide and South Australian art.

Through a series of overview chapters by Osborne and commissioned essays by a range of experts and veterans of the local scene, (alongside anecdotes from cultural commentators including poet and publisher Max Harris, critic Robert Hughes and Stephanie Britton, founding Editor of Artlink), Osborne's encyclopedic compilation of essays illuminate what she argues is the uniqueness of Adelaide's artistic landscape between 1939 and 2000, while situating it within broader cultural and socio-political contexts of Australian and international art.

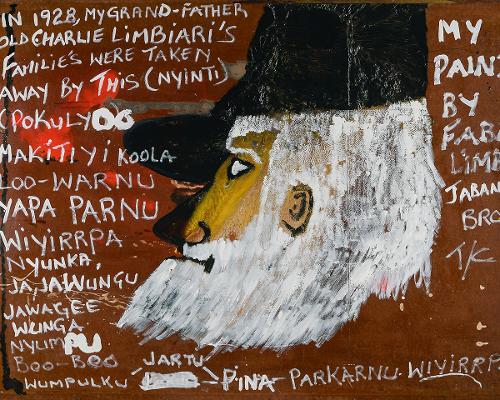

Tjukurpa – handle it. These are the words stencilled above the door into the Wati (Men’s) Studio at Mimili Maku Arts Centre in the remote community of Mimili on the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. One of Robert Fielding’s early geopolitical interventions, these aerosol words mark a threshold into the space where Fielding makes art. Placed high on the lintel, the letters herald the power of the studio and acknowledge past grandmasters, as Fielding calls them, and those to come of the Mimili art movement...

In recent years, Cairns has blossomed as a centre for First Nations artists and curators, many of whom have migrated from Cape York and the Torres Strait Islands. Along with the growing success of the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, there are increasing opportunities to show work from Far North Queensland. Artlink invited members of an emerging curatorial collective to share their insights and experiences with Hamish Sawyer, Artistic Director of NorthSite Contemporary Arts...

Like genealogies, archives hold and hide information. They ask as many questions as they answer. In 2011 in Artlink’s Beauty + Terror issue, Daniel Browning profiled Ben McKeown’s practice when, as an emerging artist, he was awarded the Victorian Indigenous Art Award. The work in question Untitled (2011) presents a strong young man in a singlet wielding two hardwood fighting boomerangs. His Aboriginality is inferred, but his personal identity is deftly masked by the weapons. There is a sparring session underway, a flirtation, a provocation, a staging in which humour and menace play equal parts. The image entreats interpretation and deflects it. As Browning wrote, its ‘enigmatic, a question mark. But what is it trying to say?’...

The expanding praxes of Indigenous curatorial and conservation roles in Australian art museums is shaped by an active response to, and challenge of, power imbalances, along with the tension between who is writing history, which artists are collected, and how both are talked about and displayed in the present. We write this essay as Aboriginal relations from the Southeast region, from Ngiyampaa territory in the northwest of New South Wales (NSW), to Bundjalung and Yuin Country within the northern and southern coastal areas of NSW. We also write as a Blak curator and conservator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at one of the country’s leading and largest collecting institutions, the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW)...

In August 2023, we (Ethel and Madeline) travelled to Sydney from Gija Country in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, where we met with Cate Massola whom we have worked with at the Warmun Art Centre and known for many years since. Our trip was to introduce and welcome a suite of paintings, by four generations of women in our family, to the John Olsen Gallery. The exhibition Nyoorn-nyoorn boorroorn daam bandarran (Country to canvas), consisted of works from the Estate of Madigan Thomas, made many years ago, alongside more recent paintings by younger members of the family. Through the exhibition, the past and present converged, making us think about the ways we work together...

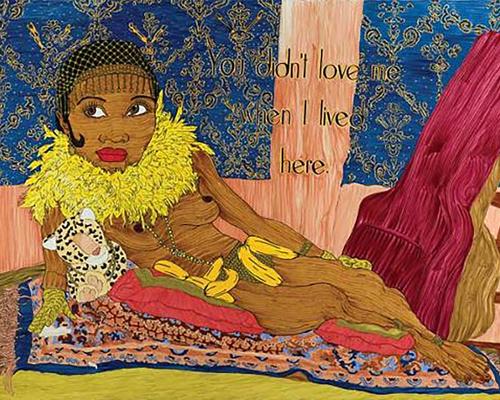

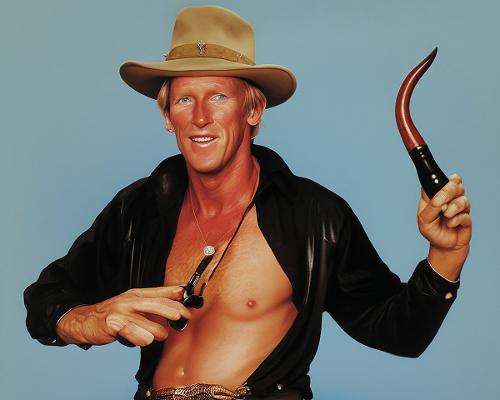

The exhibition Past Their Flesh marked a first-time collaboration between Perth-based artists’ Natalie Scholtz and Curtis Taylor. The gathered works, primarily collaborative mixed media paintings on canvas, presented roving yet condensed post-colonial fever dreams, pulling signifiers from a locus of personal-political histories and the settler-state of Western Australia. Past Their Flesh is an encounter with the ever-morphing contours of race, gender, human and non-human beings, an imaging of the messy, fleshy spaces within shifting complexes of identity. While Scholtz has worked primarily as a painter, and Taylor as a filmmaker, multimedia and installation artist, both artists have a knack for working with potent symbols drawn from Australian imaginaries—the visions, desires, projections and containments therein, and the various escape routes that visual art might plot out. Across these works they appear to doubly-condense the embodied self within wider political and relational schemas. What follows is a close reading of several selected works from the exhibition...

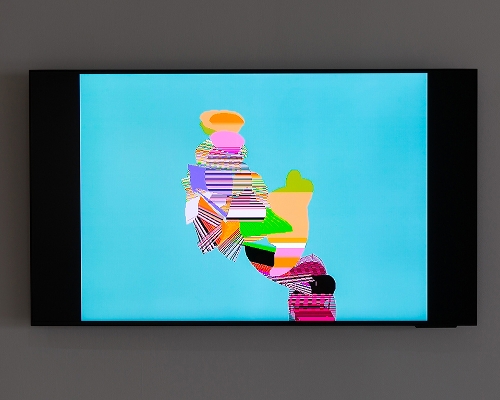

The Blue Mountains Cultural Centre (BMCC) has a long relationship with artist, educator and curator Leanne Tobin. She has been part of the art scene in the Blue Mountains prior to the Cultural Centre opening in 2012, and Rilka Oakley, Artistic Program Leader, and the BMCC team have worked with her on multiple projects as both an artist and curator. When the idea of working with the National Gallery of Australia’s (NGA) Sharing the National Collection initiative was put forward, alongside bringing First Nations video works into the World Heritage Interpretive Centre at BMCC, Tobin was invited to co-curate the project. She knows the Blue Mountains community and its First Nations artists; she understands First Nations practice at a local and national level and has personal connections with the artists selected...

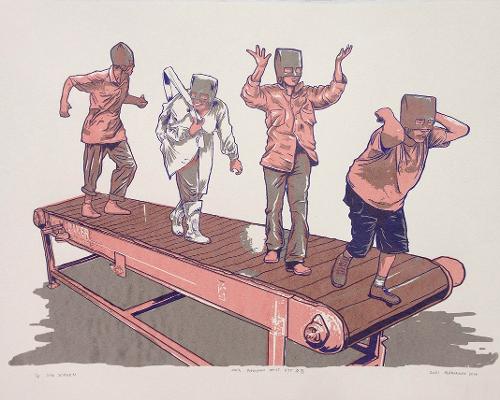

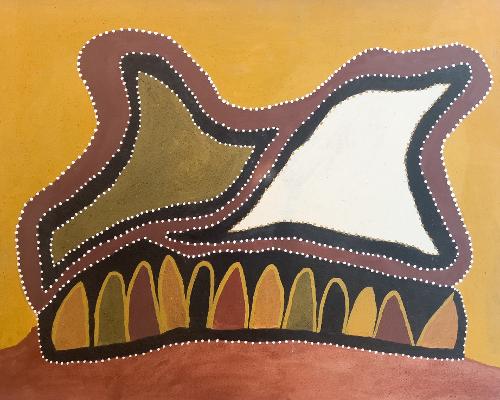

Indulkana, the most eastern community in the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, has a strong history of engagement, experimentation and innovation. The first wave of Iwantja’s senior artists—many of whom were among the first generation to see colonisers— expressed aspects of Aṉangu culture from before, during and after frontier conflict. Now younger generations of artists are rearticulating their culture amid the new frontier of western social influence. And hence, a new western emerges...

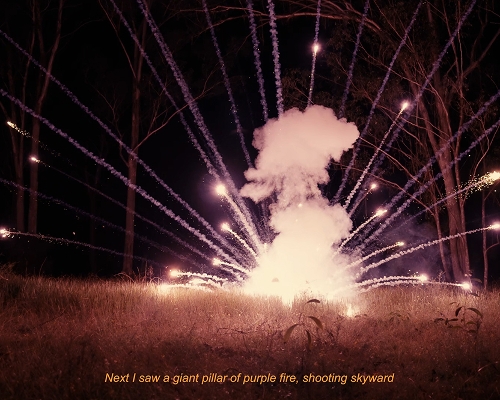

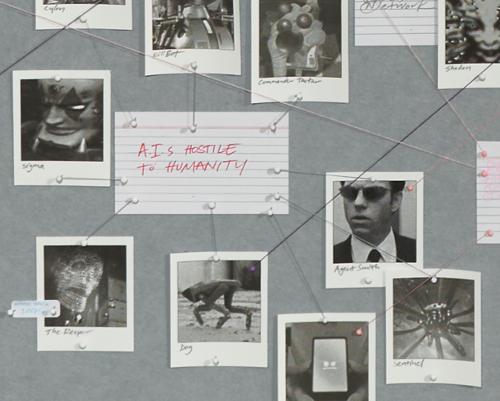

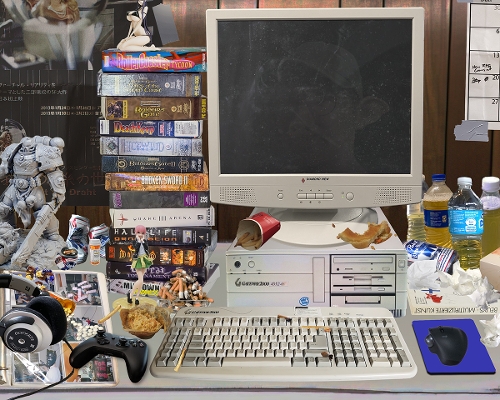

A paradox: ‘the photographic’ is central to visual culture inflected by artificial intelligence (AI), and yet AI is rapidly destabilising photographic practice. A cyclical theme, the notion of what constitutes a photograph and what it means to be a photographer are fundamentally questioned once more, especially since the release last year of novel text-to-image models capable of generating so‑called photorealistic images from text prompts (DALL·E, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, etc.). In a curious reversal of the conventional process of captioning a photograph after it has been taken or printed, professional image makers and publishers are now negotiating the ability to synthesise photographic-looking images from executable texts. In the process, the still-dominant paradigm of photography as a contingent encounter between a camera user and the world is being upended by proprietary AI algorithms trained on datasets of existing photographic images, raising vital ethical questions on authenticity, biases and authorship.

In The Economist recently, historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari claimed that ‘AI has hacked the operating system of human civilization.’ Highlighting the existential risk that artificial intelligence could possibly supersede the human mind and disrupt the order of human history, he proclaims: At first, AI will probably imitate the human prototypes that it was trained on in its infancy, but with each passing year AI culture will boldly go where no human has gone before. For millennia human beings have lived inside the dreams of other humans. In the coming decades we might find ourselves living inside the dreams of an alien intelligence.

Although Harari’s hypothesis reflects the complexity of our future with AI, throughout history technological innovations have raised concerns towards the new ‘other,’ whatever its form. So, in what way is this progression—or rather, regression—with ubiquitous AI different to any other tool humanity has previously crafted?

On the 15th of June, 2023, students from The Australian National University’s School of Arts and Design hosted a funeral and memorial service to celebrate the life (and death) of Photography at PhotoAccess, Canberra.

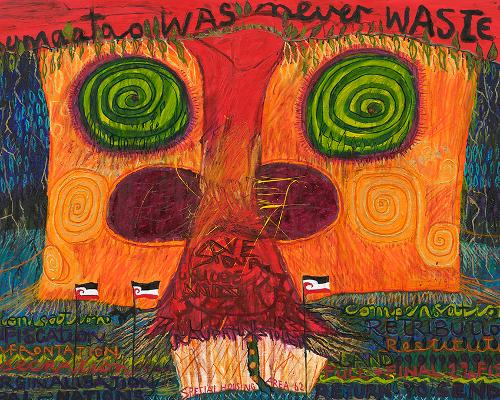

In the rapidly expanding literature on the Tennant Creek Brio, writers have touched upon a decidedly ‘masculine’ quality in the group’s work. John McDonald calls the Brio’s work ‘incredibly aggressive’ and ‘raw’ and ‘wild.’ Erica Izett, the Brio’s regular curator and greatest advocate, refers to their work as a form of insurgent ‘guerrilla theatre.’ These masculinist tendencies should be of little surprise. The Brio started in 2016 as an art therapy group as part of Strong Men, Strong Families through funding from the Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation facilitated by painter Rupert Betheras. It grew to have about twenty men involved before moving to the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in 2017, where it was declared an artist collective.

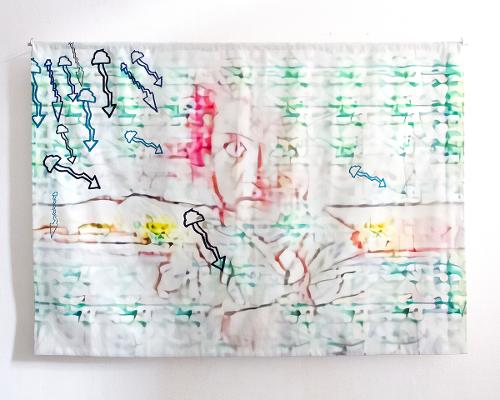

2018_watercolour and gouach on tracing paper.jpg)

_Card.jpg)