Artlink Indigenous_Working Voices has come together under challenging circumstances with the national referendum—the now ‘defeated’ Voice to Parliament—colouring so much of the past year. Our writer’s deadlines were the same week that the 60/40 vote was counted, in what was not a surprising result, but a demoralising one for many of our writers and readers. As Robert Fielding put it in his keynote at the Tarnanthi Festival launch in Tarntanya /Adelaide just days after the 14 October vote,

Our future was never yes or no; it is not black or white, this way or that way. This year has demanded every bit of energy and spirit our communities have, and still we bring you this exhibition. Still we keep our communities together, still we look to the future, still we rise.

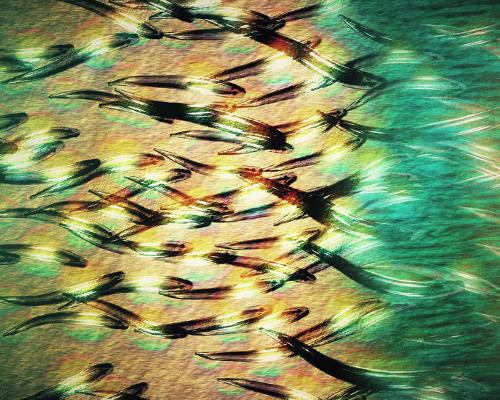

Does this sound like defeat? I first met Robert and his long-term colleague Angus Webb at Negative Press print studio in Melbourne where Robert was developing a new body of work with printmaker Trent Walker. An orator of precision and judicious words, Robert spontaneously shared some prose‑poetry he’d composed on his iPhone. It had the power of a manifesto, a veiled response to the savage media coverage (by The Australian) of art centre working relations in the APY Art Centre Collective which fanned the flames of political division. That Robert and Angus also made time to reflect on their work together at Mimili Maku Arts for Artlink is testament to their professionalism.

On our cover, Robert’s hi-vis TJUKURPA HANDLE IT! riff on the studio’s ubiquitous FRAGILE packing tape offers an agit-prop metaphor for the times, symbolising the resilience and often invisible labour shared by all the contributors in Working Voices. While 2023 has pushed some of our country’s sharpest Indigenous thinkers beyond the call of reason, this issue modestly continues the work of makarrata: a chorus of voices that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been carving out—and speaking up with—since the start of the trouble. It’s their work as artists, writers, editors, curators, conservators and educators that surfaces, sharing work that is ongoing, and work that rarely happens alone.

First Nations exhibition-making and curatorial practices feature in a range of formats, contexts and geographies. Erin Vink and Juanita Kelly-Mundine, colleagues at the Art Gallery of NSW, co-author an essay on re-spiriting methodologies true to the materiality and traditions of Southeast cultures with a case study of Andrew Snelgar’s carved shields. In Cairns, Torres Strait Islander curators Aven Noah Jnr., Peggy Kasabad Lane and Teho Ropeyarn discuss with Hamish Sawyer the various stages of their careers and Far North Queensland’s arts infrastructure.

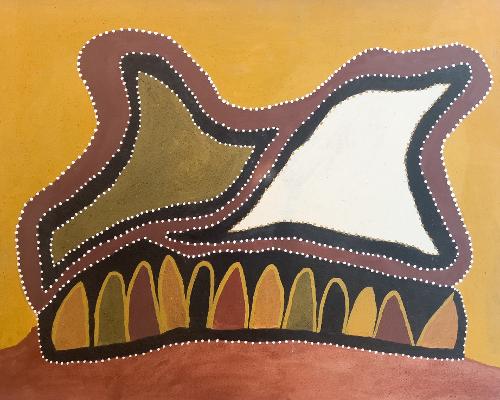

Collective research and close friendships are core to Maddison Miller’s review of ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together) by six Barkandji artists. Of this mix, sisters Zena and Nici Cumpston perform the dual role of the project’s curators—a practice Nici has honed during her years at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), notably heading up the flagship Tarnanthi. In Katoomba, Leanne Tobin and Rilka Oakley reflect on the curatorial process in working with NGA’s collection sharing initiative and integrating nationally acclaimed video works with local Aboriginal women’s works at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre. Similarly, looking both backward and forwards in time, Warmun (East Kimberley) artists Ethel McLennon and Madeline Purdie reflect with Cate Massola on differences in the intergenerational expressions of women painters exhibited in Nyoorn-nyoorn boorroorn daam bandarran (Country to canvas) in Sydney.

Responsive to the moment, Artlink’s archive is an equally rewarding muse. It was the origin of my profile on South Australian artist Ben McKeown and the people who have crossed his creative path and become intrinsic to his work, including filmmaker Mark Street.

Collaborations can be oblique or explicit, and it’s the latter which Jessyca Hutchens turns to in her penetrating analysis of new paintings made by Curtis Taylor and Natalie Scholtz. Exhibited in Fremantle, Past their flesh is a reminder—if one was needed—that the agency of collaborations lies first with the collaborator/artists, and then in the artwork as a power-object. With similar attention to the heart of relations, Tristen Harwood brings a double reading to Gary Lee’s exhibition midling and the book Heat, edited by Lee’s long term partner Maurice O’Riordan.

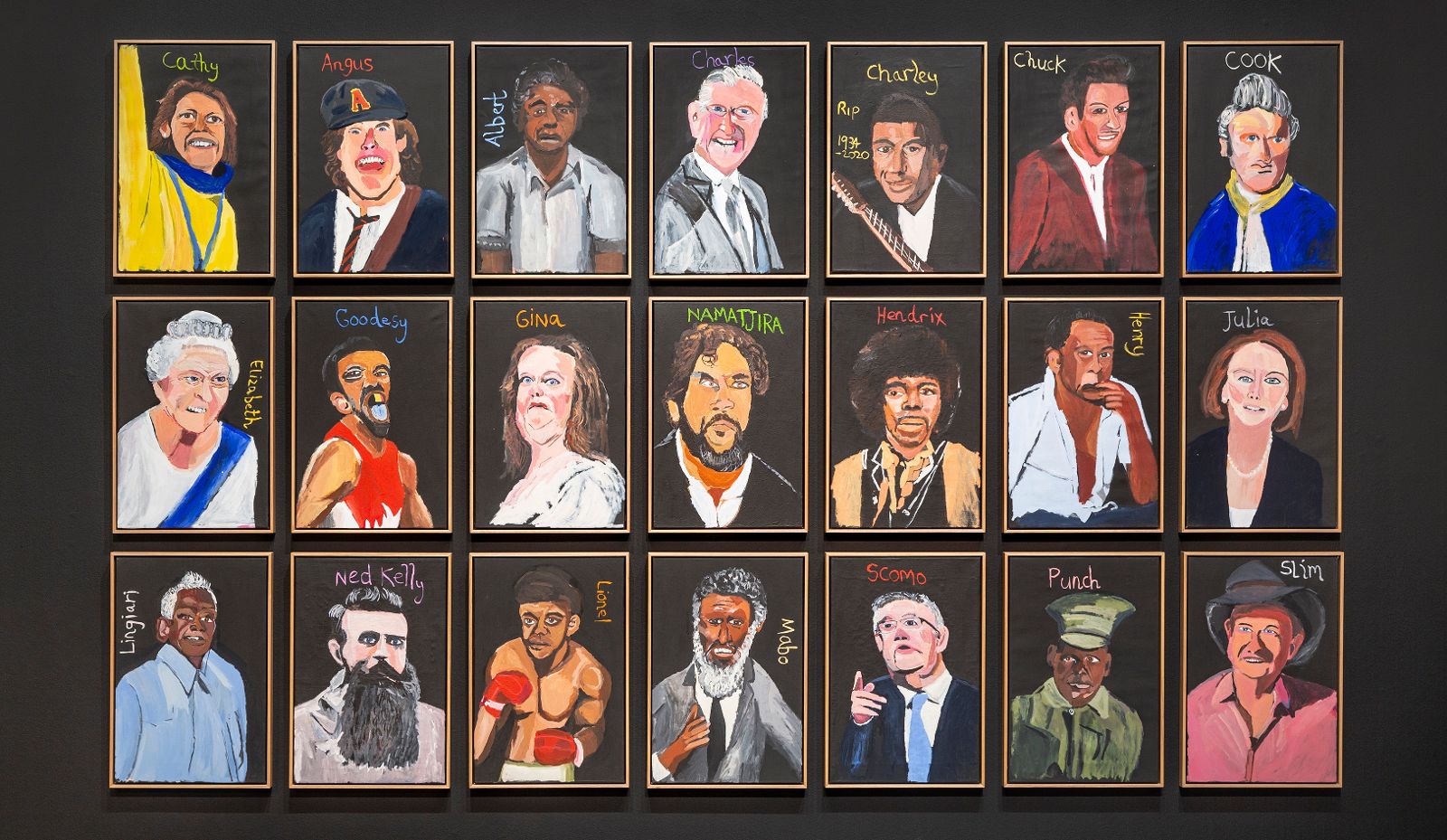

Another publication of interest is Iwantja, and we are grateful to writer Lisa Slade, Iwantja Arts and Thames & Hudson for the opportunity to publish an excerpt profiling the work of one of South Australia’s premier art centres. Vincent Namatjira is Iwantja’s indisputable king of the moment, with his survey show opening at AGSA in the post-referendum week to wide applause—when a call to silence, to Sorry Business, was ordained by the exhausted architects of The Voice’s Yes campaign. With his great-grandfather Albert Namatjira’s status as a cultural leader sacrificed to the ignorance of our nation, Namatjira has ancestral reckoning to channel, but his iconic portraits and narratives of power offer no simple reading. Namatjira’s voice is paint, which he brushes across the divide. He paints the sixty percent, cheek to cheek with the rest.