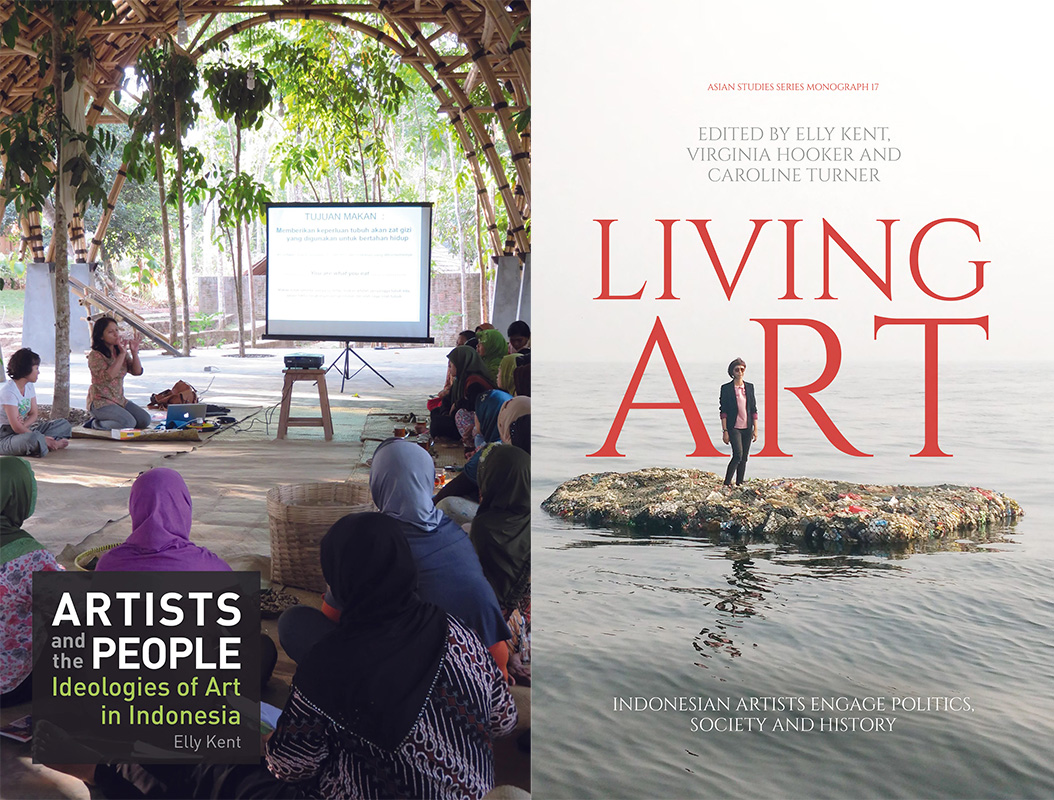

Right: Living Art: Indonesian Artists Engage Politics, Society and History edited by Elly Kent, Virginia Hooker and Caroline Turner (ANU Press, 2023)

Artists and the people: Ideologies of Art in Indonesia (2022) and Living Art: Indonesian Artists Engage Politics, Society and History (2023) take their material from over the past fifty years of developments in Indonesian art up until the global pandemic. Two very different books, they both examine and discuss selected Indonesian artists who incorporate new approaches to art practice and discourse. These include but are not limited to localised participatory practices and art made by a number of young artists as a means to remember Indonesia’s recent past.

Both publications are authoritative representatives of a ‘product of art discourse’ accessible to global academic audiences, proving that Australian scholarship is a leader in the field (though the US, Netherlands, Singapore and Japan have also shown interest in the Indonesian cultural arena). Significantly, both books appear to conclude the National Gallery of Australia’s Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia as ‘the first major survey of post-1998 Indonesian art seen in Australia and a significant number of the works were acquired for the national collection.’[1]

Elly Kent’s Artist and the People reflects her time spent with local socially engaged artists gives the writing an immediacy and a strong narrative. Kent focuses on how participatory art has applicability in the Indonesian context, not only due to the specific social setting but also because it has been researched in relation to the development of art discourse by Indonesian art and social scholars. In this, it deviates from the global discourse of participatory art which remains Eurocentric:

Participatory, relational, dialogical, socially engaged and community-oriented art practices have garnered increased academic and curatorial attention since the late 20th century, as Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics (1992) triggered interest in the aesthetic, ethical, and evaluative implications of art practised in the social realm. Yet, with a few exceptions, little academic or discursive attention (particularly in English language) has been directed towards these kinds of practices outside of the USA and Europe.[2]

In contrast to Kent's solo project, Living Art's contributing editors collect writings from a number of leading scholars, curators and artists, showing how Indonesian art has a vital role in addressing social issues and inspiring cultural and political change. A well-illustrated anthology with ten chapters, it includes a re-reading of selected Indonesian artists in the 1990s by Caroline Turner, recent perspectives on Islamic art by Virginia Hooker and the paradigm shift in historically informed art practice in Wulan Dirgantoro’s analysis of pre- and post-Reformasi artists.

Some topics rare in Indonesian scholarship are well discussed in Living Art, such as the unresolved issue of the 1965 genocide and the trauma faced by some 1970s artists; the erasure of woman’s art history (specifically, Alia Swastika’s New Order Policies on Art/Culture and Their Impact on Women’s roles in Visual Art, 1970-90s); and the struggle of activist artists in facing state and private collaborations of neoliberal repression and exploitation. A personal story from the perspective of FX Harsono about the depoliticisation of art and the repressive regime of the new order is compelling reading.

It’s fair to say the late prominent art critic Sanento Yuliman runs like an ancestor through both books. Artists and the People holds dialogues with Yuliman’s theories, mainly regarding the uniqueness of Indonesian art’s heteronomy. In Living Art, (which includes Elly Kent’s translation of Yuliman’s foundational 1979 text, New Indonesian Painting), the editors argue that Indonesian art ‘appear[s] amid living art traditions that retained important social functions for ordinary citizens’[3]. The two publication’s spirit seems to achieve beyond explanations of formalist art production and discourse, which typically take a neutral side regarding Indonesian social and political problems. By that I mean the books take a critical stance to argue that Indonesian modern and contemporary art lacks the means to address the subjugated discourse and practice in Indonesia’s post-feudalist, postcolonial setting.

For example, subjugation in the Indonesian context applies to leftist discourses and initiatives. Since the Suharto-led 1965-66 purge against the communists and their affiliations, Indonesian art has seen an absence of real contestation between ideologies. Arguably, the marketisation in higher education or academies and their relationship with the repressive-authoritarian and neoliberal state administration contribute to the situation. This relationship blocks counter or critical dialogue, and gives way to art market domination as critique, issues which are highlighted in both publications. For example in Artists and the People the participatory practices of Tisna Sanjaya, Elia Nurvista and Made Bayak are detailed, and in Living Art Virginia Hooker proposes Tisna Sanjaya and Arahmaiani’s practice as alternative modes of Indonesian Islamic art which promote socio-environmental ethics. However, such artistic practices need more depth of discussion across the nation, as expressive of the minority and subversive practices that exist within the pseudo-democracy of Indonesia—and the neoliberal powers wielded under post-Reformasi regimes.

Importantly, the books refrain from lingering on cliched topics like the debate over the identity of Indonesian art or the myths of the Bandung and Yogyakarta Schools, which previous texts such as Helena Spaanjard's Artists and their Inspiration: A Guide through Indonesian Art History, (1930-2015) (2016) have reproduced. Living Art does however set the stage in the form of a narrative timeline in the editors’ chapter Contextualising Art in Indonesia’s History, Society, and Politics. The framing essay presents the important milestones in Indonesia’s art development since the pre-colonial period to the present by incorporating non-typical materials to situate the development of Indonesian art with Indonesia cultural and social circumstances.

Living Art in particular fills in the gaps of forgotten discourses, while Artists and the People examines important art practices today that have escaped critical readings. In this way, the books are distinguished from previous Indonesian art discussions that do not have a strong contextual ground in Indonesian cultural phenomena. The Indonesian classical texts used in Living Art (in addition to Yuliman) including Jim Supangkat’s A Brief History of Indonesian Art (1993) will provide new scholars interested in Indonesian art with an introductory and historical knowledge of the field. Living Art’s detailed art historical chronology, location maps, colour illustrations and comprehensive bibliography also suggests its positioning for the academic market.

As the lack of local critical scholarship on Indonesian art is worrisome, the publications make a significant contribution, (despite being published solely in English), to Indonesian artists and art students. They also signify how Australia’s international scholarship holds cultural institutional power in the Asia Pacific region, and that Australian researchers have empathy towards Indonesian artists and culture. Collectively, the books invite Indonesian scholars to theorise the overlooked social or humanities thinking of Indonesia’s public intellectuals or art intelligentsia. They could also provide a benchmark for another research project by Indonesian academic communities. However, it would be better if Living Art editors had invited more of the younger generation of writers and scholars to contribute to the book, instead of, or even alongside, its prominent and established names. This would give us a diagnostic paradigm in examining artistic practices within contemporary Indonesian art, and the agency to write more of our own accounts of its development.

Footnotes