Once we looked to the stars to imagine ourselves within infinity. Using our mind’s paltry processing power, we invented a transcendental intelligence: art and religion followed as enduring signs of our vivid imaginations. Now data forms our heavens and algorithms our Gods. Miraculous. Ubiquitous. Omnipotent. No, AI didn’t write that. But it wrote this in partial response to my question ‘should art writers be worried about AI?’:

Art writing often involves conveying the emotional, intellectual, and cultural significance of artworks. The human element of interpretation, personal experiences, and subjective responses are valuable aspects that AI may not fully capture. Art writers can continue to foster human connection through their unique perspectives, narratives, and the ability to evoke meaningful experiences for readers.

Patronising? Clichéd? Anodyne? As After AI goes to print, Artlink does not have a policy on AI, despite its ramifications for art publishing and the creative industries. We are not alone. In January this year the Australian Government released their much anticipated Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place, a National Cultural Policy scoping ‘the next five years’. It makes one brief mention of AI in its 116 pages: ‘Creativity and design thinking have been shown to be increasingly valuable to a range of different disciplines such as advanced manufacturing, scientific research and artificial intelligence’. I’m assuming AI didn’t write that, although it sounds sufficiently generic. Meanwhile governments worldwide are racing to regulate humanity’s genie. The EU has just launched the world’s first AI Act, and the UK is planning a global summit on AI safety later this year. Like the early days of the global pandemic, AI is proving to be a borderless state, but there’s no vaccine in sight.

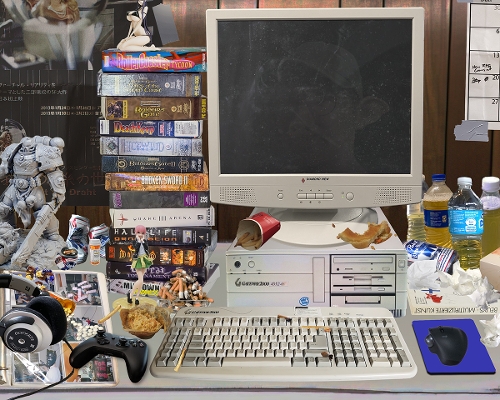

But is AI really so sudden? The gateway drugs of FAANG (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) have been rampant for long enough to induct us into ‘algorithmic citizenship’, to borrow from James Bridle. And is this ‘new’ really so new? The advent of photography, the established genre of science fiction and the disruptions of Surrealism and Pop are some cultural touchpoints. On a technological timeline, it was 1950 when British logician Alan Turing published Computing machinery and intelligence and American computer and cognitive scientist John McCarthy coined the term ‘artificial intelligence’.

For most of us, the ‘AI movement’ arrived in 2021 when the US private company OpenAI’s text‑to‑image model DALL·E landed. Like its rival siblings (Midjourney and Stable Diffusion among others), the models are becoming more powerful—and more carbon-intensive—with each release. By late 2022, OpenAI’s ‘plug and play’ ChatGPT was game on. In February 2023 the paid subscription model ChatGPT-Plus followed, after the free version had attracted ‘hundreds of millions’ of active users over the summer/winter months (pick your hemisphere). As of July 2023, it is not officially available in China.

After AI’s writers are alert to these historical intersections and to a panorama of imaginary futures. What begins to emerge is a nascent discourse on AI, identifying its leading thinkers. Whether writers lean to cautious optimism or critical alert, they canvass AI, as ChatGPT informed me,

… in specialized areas, such as in‑depth analysis, contextualization, or engaging storytelling… developing the unique perspectives, critical analysis, and creative interpretations that AI may struggle to emulate.

Riding the zeitgeist in the anachronistic magazine vehicle, material dates quickly. We become an archive. A data source. A scrape asset. Julianne Pierce, a founding member of the VNS Matrix, has turned her attention to Artlink’s earlier scrapes with cutting-edge media art, and we are never immune to the temporal or cultural cringe.

At first, the AI turn seems a photographic problem, and Daniel Palmer and Katrina Sluis give an overview of photography’s central role in AI’s development. They introduce key terms, cite recent image-driven debates and speculate on the implications for photo media artists working with and against the grain of AI. Sluis’ students at the ANU x PhotoAccess R&D Lab in Canberra take the critique a step further with their parody on the death of photography.

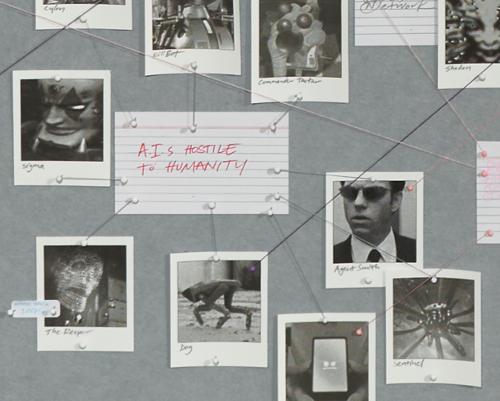

Long-range dystopia and techno-pessimism informs Sophie Knezic’s piece on AI and sci-fi, using Jon Rafman’s post-apocalyptic films as a portal, while for Wes Hill, the hyperbole surrounding AI has been around before in the name of Pop; in Hill’s theoretical analysis of the moment, Andy Warhol’s ghost leads the therapy session, and as users/consumers and producers, we must be careful what we wish for. Would André Breton be as bold today as he was 99 years ago penning his first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924): ‘Beloved imagination, what I most like in you is your unsparing quality.’

Seeking an image licence to reproduce Warhol’s work when Artlink could have AI-generated our own ‘black and white Rorschach painting’ is not without irony, but given the grey areas of copyright law and machine-generated images, we’ve remained faithful to the capitalist, market-driven system, wrestling with issues of attribution and context. Appropriation? Homage? After [insert prompt]? Leading copyright lawyer and Artlink Board member Ian McDonald brings some sobering observations to this new legal (lawless?) frontier. On the other hand, pilfer demonstrates that, wherever you’re positioned in the AI pipeline, darkness and light are just a hyperlink away. Whether liaising with René Magritte or Stable Diffusion, satire and chance get equal billing.

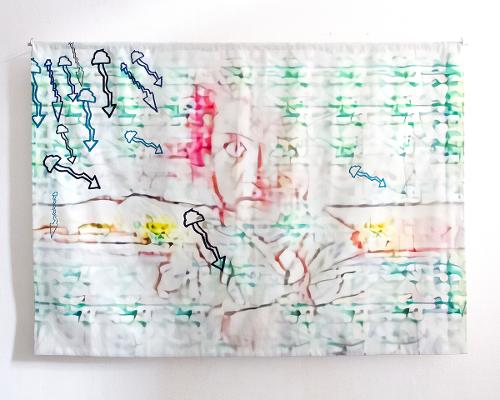

John McCarthy is widely credited as ‘the father of AI’, but as Gretta Louw asks, who is its mother—or more pointedly, who will parent AI? AI’s sentience and our interpersonal relationships with ‘the bots’ are at the heart of Louw’s ethical probe. Inter-species relationality also figures in Cameron Hurst’s appraisal of Georgia Banks and Amalia Lindo’s AI–responsive works in Melbourne Now (2023). They’re among Australian artists ‘embracing AI as a partner in the creative process to access new resources and expand their creative capabilities.’ (Thank‑you ChatGPT—such a techno‑optimist, and so free of irony.) Other Australian artists exploring AI’s limits and potential are profiled by Amy May Fischli, and in Jess Herrington’s essay artists who teach in the age of AI are effectively at the front lines of an education paradigm shift.

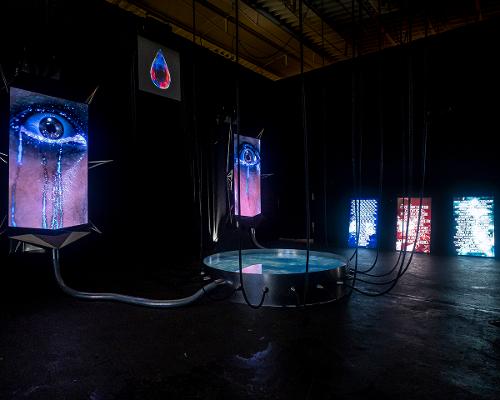

It’s a global phenomenon, but from the underbelly, AI seems like the love-child of Silicon Valley, Hollywood and the Pentagon. Refik Anadol, famous as Google’s first artist-in-residence, has shown down-under, with the sensationalist Quantum Memories (2020) at NGV. Anadol’s website describes his work as ‘sensorial autonomy via cybernetic serendipity’, but numerous critics have been more direct—and more hostile. By right of reply, Melissa Bianca Amore’s conversation with the artist offers an alternative appreciation of his thinking and his influences, while raising broader existential questions about memory and perception.

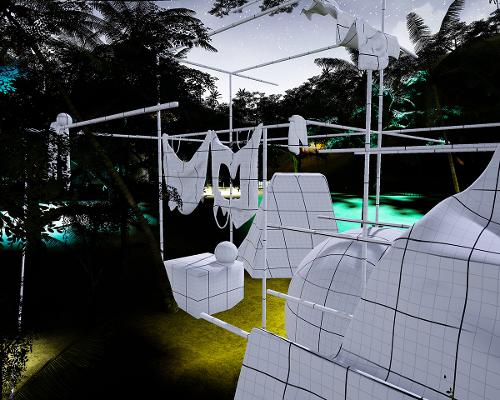

Pioneer of machine learning and AI art Jon Rafman has also attracted polemic responses, but like Anadol he embodies an artist technically invested in AI before the contemporary frenzy. Rafman’s worlds, scraped from our own, are unsettling, but they’re also saturated with allegory and ambivalence. Using customised AI models, his protagonists wade through a web of Reddit-inspired psychodramas, transitional and dystopian, including the fictional characters on our cover. A hard-cropped film still, it captures our time-sensitive tech-moment in all its uncanny, glitchy frisson: are they macabre surreal zombies fleeing some malevolent force, or are they liberated AI figments, victoriously dancing towards us?

If AI was a blind-spot in the National Cultural Policy, AI’s ‘will to power’ has galloped from the allegorical horizon to our screens like horsemen of the apocalypse. ‘Adversarial’ and ‘benevolent’ binaries have become central themes in AI discussions, with the obsolescence regime (where every industry, corporation and government is AI‑dependent) and misaligned AI (where it doesn’t like or care for us) predicted as our next Armageddon. (Move over climate crisis and mass extinctions). But there is techno‑optimism too, and AI has potential as a saviour in many fields. In her essay, Amanda Mwenda turns on the bias and blind-spots within emerging AI discourse and explores design fiction and tech-futures that can be harnessed for ethical ends. Her case study, Exhibit A-i: The Refugee Account, is exemplary of the emerging form of synthetic truth-telling with human rights and social justice as its endgame.

Art critic Hal Foster’s recent collection of essays What comes after farce? poses salient questions for our times. In his chapter on machine images where ‘…in seeing a little we are edged into believing a lot’,[1] he concludes that ‘… “literacy” [of representation, meaning and critique] is a problematic term—it is intrinsically exclusive, and it sets us all up for perpetual retraining—but what counts as the requisite competence in this strange world?’[2] In other words: what comes after AI?

Footnotes