Tasmanian Gothic is an enduring trope used most visibly, in recent decades, as a tourism device. It sells the troubled island back to its mainland counterpart and works on the gourmands and intrepid Patagonia-clad campers among us, often one and the same. Certainly, to this outsider–it having been more than a decade between drinks–Tasmania does feel shrouded, ill at ease. The unmentionable hangs in the air. Coincidentally, the tourism slogan ‘Come Down for Air’ is as preternatural a figuration of Tasmania–island as tabula rasa–as a brooding, gothic landscape that threatens to swallow you whole (see the man-eating waterways of last year’s ‘feminist noir’ hit television series Deadloch). The ahistorical conditions of Tasmania are sold to us against a backdrop of real, unsettled histories; as Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough describes it, the whole place is a ‘crime scene.’[1]

Although an unlikely lens for reviewing the 2023/24 summer shows at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), particularly given all three exhibitions feature international rather than Australian artists or works, the feeling is hard to shake. At the time of viewing, the country was on a precipice, just two weeks out from the Voice to Parliament referendum vote. Driving into Hobart, crossing the River Derwent, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price came over the radio–an ad for the No campaign. That evening at a local pub, Rachel Perkins and Paul Kelly sat just a few tables over, on tour as part of the Yes campaign. We now know how that story goes.

The particulars of time and place are fundamental to reading French artist Jean-Luc Moulène’s self-titled solo exhibition. Namely because, of the three shows that opened in September 2023, his was most troubling in its claims for universality and the underexamined role of the peripatetic international artist, particularly amid such a charged political atmosphere in Australia and the more generalised post-pandemic push towards business as usual.

Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams is a sparse exhibition featuring four elemental sculptures–boulder-like forms in wax, sandstone, zinc and wood–alongside a cow bone propped between ceiling and floor, and two earlier works reprised from Moulène’s archive. All Moulène’s objects are deeply entangled, not just in the physical processes and Teams engaged to produce them, but also in the pedigree of the materials. The lithe cow bone for example, Axe (Axis) (2016), is described to have been ‘boiled clean of its meat, buried for a time, and exhumed at Bushy Park’, a rural township between Hobart and Queenstown.[2] Tasmanian Gothic rears its head; the earth claims and rebirths us all. While the significance of Bushy Park is left up to us (no further information across MONA’s mobile app ‘art wank’ elucidates why Bushy Park in particular), it’s not such a stretch for an exhumed bone to conjure long standing repatriation battles over Aboriginal ancestral remains or recall the controversies of Mike Parr’s 2018 subterranean performance Underneath the Bitumen the Artist. Tasmanian ground is loaded.

Material pedigree continues with Moulène’s four boulders. Travelling further northwest, Hydrowood Knot (2021) tells the tale of a new industry in Tasmanian forestry where timber is dredged from the man-made depths of Lake Pieman. Until recently, rare species of wood, primarily salvaged for boutique architectural finishes (and now artworks), had been ‘lost’ to Tasmanian time.[3] The Triassic rock of Sandstone Abstract (2021) similarly conjures the protohistoric while Fixed Zinc (2021), smelted at Bell Bay in northern Tasmania, was inspired by the zinc refinery situated on the River Derwent. During his artistic reconnaissance in 2018, Moulène was surprised to encounter such industry on the banks of an otherwise pristine river.[4]

Moulène’s focus is material transfiguration. Water shapes molten metal; a rock, taken from Beqaa Valley in Lebanon, is scaled up in Gosford sandstone; forms shift from positive to negative to positive (Wax Larva [2021], a great hunk of robotically carved wax, is ghosted by the lost wax casting techniques of Fixed Zinc). The artist is attempting to manipulate the laws of physics via a globalised team of 3D specialists, curators and manufacturers.

Moulène's quest for the universal seems sincere. To produce art beyond the trappings of nations, politics, identity, time, remains a holy grail for many artists, especially those working trans-geographically or chasing a formalist ideal.

We went for two days to Freycinet. For me, it was part of the south of France, part of Morocco, part of Mexico. We always interpret. I try not to be, we say, ‘stupidly local’, it means with clichés. The sky is everywhere.[5]

There is truth to the insight. We could all do with some relief from the institutional formulas that trap and categorise contemporary artists (and curators and writers). Perhaps the air is fresher down here after all. But Moulène’s proposition is hard to reconcile considering his materials are deeply of place and marketed as such. Moreover, his objects are resolutely objects. They are great hulking sculptures you imagine being craned into the gallery, physical matter extracted from somewhere–in this instance, Tasmania and New South Wales.

The work that best captures this hypocriticism is Errata, (2002–2013). Within slingshot of the four boulders, Errata constitutes nine palettes of stacked Jumex cans–Mexico’s most popular juice and nectar producer–in a towering Judd-like arrangement of hyper-coloured cubes. Moulène intercepted the manufacturing process, stripping the cans of their trademark branding (a reverse Warhol, if you like), and re-presented the objects as pure minimalist form. We are given the etymology of the title–erratum, meaning mistake in printing or writing–as a clue to Moulène’s hand in an otherwise seemingly straightforward Pop readymade.

In geological terms, an ‘erratic’ is the phenomenon of a rock out of place, from the Latin errare meaning wanderer, or error, to wander from the truth.[6] These travelling rocks, transported by natural forces and through human endeavour, are marked equally by place and displacement. Looking at Errata it’s hard not to think about origins (and divergence from the truth). It’s hard not to imagine Jumex’s industrial plant outside Mexico City, long hot days, the monotony of factory work, the conditions and lives of factory workers. Even freighting the work to Tasmania would normally–with branding–count as some serious food miles, but is rarefied here. Errata is made all the more complicit knowing Eugenio López Alonso, the heir of the Jumex fortune, is a world-class contemporary art collector.

Just as the cans are erratics, so too are the boulders. Moulène’s carefully chosen single-origin materials speak less to their beginnings, less to the real politics, time or place that entangle their meaning, than they do the contemporary phenomenon of optimisation. These objects are tourists on a global circuit, following millions of other everyday objects on the same pilgrimage.

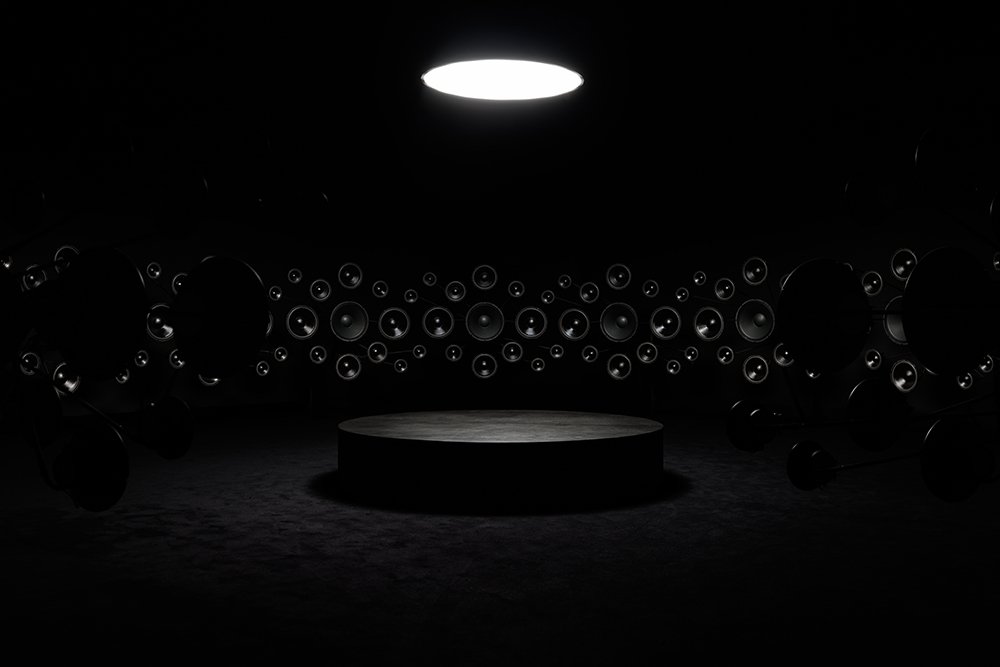

Deep within the subterranean architecture of MONA another erratic materialises, this time hailing from Iceland. Hrafntinna (Obsidian) (2021), a single room installation by Jón Þór “Jónsi” Birgisson–best known as the lead vocalist of experimental rock band Sigur Rós–is a sensory ode to Fagradalsfjall, the Icelandic volcano that erupted to international attention in March, 2021. At the centre of a rotunda of speakers, in near darkness, the immersive soundscape builds in topological layers. Deep rumblings of a volcanic interior vibrate from below; Jónsi's voice, cracking and soaring in his iconic mournful falsetto, sweeps around the room in a spatial sleight of hand; the warming scent of fossilised amber and birch tar fills the nostrils. Produced while watching his native Iceland erupt from a distant Los Angeles studio, Jónsi unable to return home due to the closed borders of the pandemic, Hrafntinna (Obsidian) is a devotional work, a lament for landscape.

Previously staged in New York and Canada, Hrafntinna (Obsidian) takes on a new dimension in the Australian context. Iceland, geologically speaking, has some of the youngest bedrock in the world; new ground is actively birthed by way of volcanoes like Fagradalsfjall. There is poetic asymmetry to experiencing the work on one of the most stable tectonic plates, one of the oldest, flattest landmasses on Earth. Hrafntinna (Obsidian), Jónsi's volcano, is an erratic–it offers us contrast material. It offers the pleasure of encounter with a rock out of place.

After navigating the architectural expansions and contractions of MONA’s labyrinthine building, Hrafntinna (Obsidian) and Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World–the last of the three summer exhibitions–provide sensory reprieve. They aim as close as possible to the secular religiosity that contemporary art galleries often strive for (particularly MONA), the former through its transcendental takeover of one's faculties, the latter by way of the spirit.

Heavenly Beings is a scholarly, dense exhibition of more than 140 devotional icons, amongst maps, artefacts and objects, spanning the 14th to 19th centuries, cloistered into darkened thematic rooms. From a central vestibule–a purgatory in the clouds–you can choose your pilgrimage: Holy Guardians: Angels, Saints & Martyrs; Holy Journeys, Holy Land; Feast Icons; Mother of God; Faces of Christ and Holy Thresholds.

Heavenly Beings was first staged in 2022 at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, curated by Dr Sophie Matthieson. For it's second iteration, Matthieson worked closely with MONA’s Senior Research Curator Jane Clark to bring the exhibition to Tasmania–a feat of national significance given Australians, typically, need to cross the globe to witness such a wealth of works. The two curators generously frame the exhibition for religious and atheist audiences alike, and in spite of (or perhaps due to) their historical specificity, the images strike as perennial. The hagiography, scenes of suffering, violence, salvation and rebirth, painted in painfully intricate egg tempura and gold leaf, are as Australian abstractionist and painter of Byzantine icons Leonard Brown describes, like ‘praying with your eyes open’.[7]

Hrafntinna (Obsidian) and Heavenly Beings offers audiences the best of David Walsh’s coffers. Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams is closer to late-stage decadence. In the age of global contemporary art, of course the visiting international artist needn’t address the locals, lest we summon the spectre of Australian parochialism. Nor should artworks be produced only by way of consultation (an institutional template that can, oftentimes, feel pitched to exonerate earlier crimes). Moralising Moulène’s objects may well be a symptom of our times, and as soon as the critic dictates the rules of engagement, we have failed artistic liberté. But the trio of exhibitions are a timely reminder that, no matter our faith in the church of contemporary art, artistic divination is never neutral.

Footnotes

- ^ Julie Gough, Tarnanthi 2021, Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 2021, p60.

- ^ ‘Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams’, MONA website, accessed 30 September 2023.

- ^ 'Our Story’, Hydrowood website, accessed 30 September 2023.

- ^ This information is drawn from the Jean-Luc Moulène and Teams exhibition text on 'The O’, MONA’s mobile app, accessed 29 September 2023.

- ^ Jean-Luc Moulène, interview with the artist, Hobart, 29 September 2023.

- ^ Tim Creswell, “Nowehereisland: A Project by Alex Hartley”, Art Review, 56 (Jan-Feb 2012): 93.

- ^ Leonard Brown, “Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World”, Artist Profile, 65, accessed online, 13 January 2023.