In their 2022 book Turning Archival: The Life of the Historical in Queer Studies, editors Daniel Marshall and Zeb Tortorici draw attention to the ways in which archives have categorically failed to capture queer historical experience, while also insisting on the critical significance of queer archival practice as the basis for new ways to recognise the past and revivify queer histories. Queer archiving originally gained traction, they argue, from ‘liberation-era struggles to turn away from histories of omission’, with early practitioners seeking to make ‘a stand on the grounds of evidence—that gender and sexual difference had left historical traces’, and that attending to those traces might lead to a ‘renegade preservation of … dissident historical knowledge’.[1] As Lennard Davis cautions, however, ‘there are limits to our abilities to recover the past, particularly when we are dealing with marginalised groups

. . . it may even be that those remaining documents are so imbricated in an ideology of concealment and repression that a notion that a clear reality can be recovered has to be rethought and re-theorized’.[2]

Redressing the systematic and violent exclusion of queer lives and bodies from the archive is complex and challenging work. The approach cannot be limited to recovery and revision; it must also incorporate preservation and futurity. When Walter Benjamin wrote in 1935 that ‘to live is to leave traces’, he was keenly aware that the visibility of such traces is deeply enmeshed with social and political inequalities that propagate structural oppression and invisibility of marginalised groups within specific milieus.[3] For queer archival practice, this means that, as Marshall and Tortorici acknowledge, ‘appealing in any straightforward way to the merits of evidence risks incorporation with within those historical and often juridical structures of power that have policed and regulated queer life in both the past and the present.’[4]

The KINK collective (from which we write, collectively), was borne out of a desire to create a platform dedicated to the rich history of queer Australian art in all its varied forms. One method of combatting the issues outlined here—and it is perhaps one of the most common in the diverse field of queer theory—is to pay attention to gaps: attending not to what is in the archive, but to what has been left out. There is no archive without an outside, without an exteriority, as the work of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida (notably in his canonical text Archive Fever), reveal. Any attempt to capture the vast terrain of queer experience that has been regulated, modified, silenced or repressed from the archival imaginary is, in Marshall and Tortorici’s words, ‘a struggle against reading evidence straight, not least because the very idioms and institutions for the production of archival knowledge continue to be so deeply enmeshed in colonial matrices of value, authority, access, and power’.[5] And we would add, not just colonial matrices, but also the patriarchal, sexist, homophobic, heteronormative, racist, misogynist matrices that continue to make up the core of institutional memories. The issue, then, is not with the reparative location and restoration of “evidence”. It is with acknowledging that evidence around the visibility and interpretation of queer experience is always in question, always needing to be read against the grain of the framing devices that seek to regulate and disguise its productions, meaning, and reception. What counts as history, and for who does it count?

After KINK’s initial community consultation and an exploration of how a queer representation of queer history might be born, we began the slow work of developing a free, publicly accessible online archive/history of queer Australian art. One of the guiding principles is that queeraustralianart.com will be dedicated exclusively to the representation of LGBTIQ+ artists: we are not interested in queering works by straight artists. The long-term goal is to publish a book that speaks to this transient and often fugitive history in which materials are so dispersed. KINK is emphatically collaborative and purposefully multidisciplinary, consisting of a group of art historians, curators and artists who each have a personal desire to redress this absence, and to produce a resource that we all wished had been available to us in our work as queer practitioners across various fields.

Bringing together Australia’s vast, fractured and diverse queer art history is no small task. Traces are missing, artworks lost, careers lose momentum, people have passed away (and their memories with them), and the ebb-and-flow of the public’s interest in LGBTIQ+ art more broadly are just some of the challenges of this project. One of the main goals is to work both with the recognised and the unrecognised. This means relying on a network of cultural materials including holdings of institutions, commercial galleries, state collections with oral history, ephemeral material, and individual donations. We think of flyers and pamphlets for exhibitions, drag shows, experimental arts events, dance parties, boxes in people’s garages, cupboards, attics, the reviews of queer art initiatives in street papers, zines and newspapers from the 1990s that will likely never be preserved in digital—or any form—at all.

The important work of organisations like the Australian Queer Archives (AQuA) in Naarm / Melbourne provides an essential foundation. First established in 1978 and now with a 200,000 strong collection of archival, library and gallery material relating to the history of LGBTIQ+ life in Australia, AQuA contains an abundance of material relevant to the development of a queer Australian art history, although sifting through the vast holdings collected from individuals, organisations and activists to locate the ‘art’ in the archive across the years is not a straightforward task.

Histories of queer exhibitions are also often tied up in the archives of individuals and galleries or arts organisations whose holdings have yet to be digitised, or even fully catalogued. We think of the boxes of physical materials held by Artspace, for example, or Performance Space, both based in Sydney on the lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, or Gertrude in Naarm / Melbourne, or the sadly defunct Australian Experimental Art Foundation on Kaurna land in Tarntanya / Adelaide, merged with the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia (CACSA) and now Adelaide Contemporary Experimental (ACE). The Australian Centre for Contemporary Art’s digital archive is one positive model for how this kind of content might have a second life in the online realm. We are aware that Artspace is in the process of digitising their archival materials, as are Gertrude. But it is time-consuming work, requiring commitment and budgeting often beyond the resources of many smaller institutions and collectives.

Because queer art is also inseparable from queer community, capturing the diversity of practice cannot be achieved by looking either to the archives of Australia’s leading contemporary art spaces or to the collections of large, state-based institutions. It is not currently possible to key-word search for LGBTIQ+ artists in most of the largest catalogues of public art collections in Australia (a functionality that we hope may be redressed in the future). But even if all the works by queer artists from state and national galleries, museums and libraries were successfully catalogued and collated, the results would not amount to a complete history of queer art in Australia.

This is partly because the kinds of work collected by state institutions are often the most sanitised and palatable in terms of queer aesthetics, and are not fully representative of the diversity of queer practice. This was evident in QUEER: Stories from the NGV Collection (2022) the sprawling and, at times, unfocused exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria where explicit depictions of sex and sexuality were missing. Unsurprisingly, the majority of queer (gay) works collected by institutions, especially from the second half of the twentieth century, are by white male artists. Recently we have seen and welcomed policy announcements from the NGV and National Gallery of Australia committing to diversifying their collections through works by queer, non-binary and transgender artists, the latter no doubt shaken up by discovering its own paucity of representing women artists which their revisionist feminist project, Know My Name, revealed. We will be watching closely, and we are prepared to hold these institutions to account.

Remnants and traces of queer lived experience are scattered in archives and collections across the country, from the activist badges, posters and t-shirts held in the collection of the State Library of Queensland, Meanjin / Brisbane for example, to the extraordinary outfits worn at Mardi Gras parades now in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, to the papers and newspaper clippings held by the previously named Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (whose holdings are now folded into the collection of the AQuA). But queer history is also heavily reliant on the lived experiences of individuals, something that can never be captured by institutions. It lives in queer bodies, words, stories, memories, circulating amongst friends, lovers, collaborators and accomplices. How to capture something as amorphous as a rumour, a secret, a desire? A dedicated oral history component to queeraustralianart.com is one possibility for vocalising previously unheard histories.

One benefit of not having a rich and complete archive of queer history to draw from is that we have had the opportunity to dream together, imagining what form an archive of queer Australian art might take. Fluid, responsive, and evolving, as all queer methods should be, this project has morphed into much more than we initially imagined. Our project is deeply rooted in ongoing community consultation, which will continue for the life of the project, and hopefully beyond. While we don't imagine this project will please everybody (because how could it!), it does acknowledge that queer history is multifaceted and queer methodologies are rich and varied. But equally, we don't claim to have all the answers. We are not experts in the field of queer Australian art. We are a group who came together with the goal of working with our community to pull this history together because it has been absent for too long.

As such, the form and content of KINK’s online archive of queer art has been shaped by a number of conversations between KINK and the wider community about how a platform such as this might make queer art history more visible. These took place through ‘town-hall’ style community consultation sessions, which included discussion of what a queer Australian art history should and could look like. Attended by artists, writers and stakeholders, this was the beginning of a series of conversations which we intended to hold across the country, with more forthcoming. Initial responses were wide-ranging and provocative: what is the difference between ‘queer’ art and LGBTIQ+; how to approach the work of artists who are not comfortable with the term ‘queer’ or who identify elsewise; how to engage with deceased estates of artists whose families may be reluctant for their relatives to be presented as lesbian, or gay, or bi, or trans? It is important to KINK that all living artists in queeraustralianart.com are able to give permission for their inclusion in the archive, including permission for images of their works to be reproduced under the broad frame of ‘queer art’. And yet, a question remains about how to manage estates and families who re-closet deceased artists—perhaps due to the stubbornly conservative nature of the Australian commercial market—whose practices are queer and historically important. Is the answer really erasure from a context in which their legacy is vital? For example, it is disappointing to the KINK team that some of the most historically significant queer artists have had estates refuse inclusion in this resource, such as that of the late artists James Gleeson and Jeffrey Smart.

Beyond the critical importance of drawing on less formal, personal or non-institutional collections, KINK’s work recognises the importance of centralising histories and memories in an accessible way that avoids the traps of “straight” historiography. As such, the platform eschews typical chronological structures of narrativising history—partly in recognition that queer time is necessarily in opposition to dominant “heterochronormative” temporality— but also because of a belief that users should be able to control their own temporal parameters: shifting the resource to become what is important to their research, interests, or simply, their specific outlook. Instead of linear narratives, the database operates rhizomatically, attempting to illustrate the contemporaries of particular artists, artworks, or exhibitions at any specific time.

No event or work happens in isolation and by linking specific works with related shows or curators of the same moment, a deeper picture of each succeeding present is illustrated. Queer artistic ecologies are revealed and recorded. For example, for those whose focus is on exhibitions or curatorial methods, the database can be tailored to specific kinds of queer artistic outputs. In this fashion, histories that are both specific and broad can emerge in tandem. This methodical work will take years, but the result will be a repository in which those who have fallen out of the frame are now reinstated, those who never were in it now are, and those who wish to define their own structure of representation within history can do so. More than simply a repository of data, KINK’s platform in the future will also be a site of making and writing history: a space for publishing new scholarship to add to the existing resources that the database offers.

One of the other benefits of grounding this project in digital space, at least initially, is the flexibility that the online platform allows for amendment, expansion, correction and adaptation as the work continues. Right from the start, we knew that in addition to providing an accessible platform for the dissemination of an archive, the potential for ongoing community consultation for the work needs to remain alive. Live and immediate feedback and responsiveness of the queer archive is essential. Embracing the digital form, allowing the continued development of the archive to be made public—never complete, never finite—means the project continues to evolve through a more horizontal engagement with diverse communities. Unlike a published book, this approach allows for the contestation of knowledge to be shared; correcting mistakes if they are found, expanding areas where required. Our diverse communities can actively contribute to its growth and once the framework is set, can expand the project into directions not yet imagined. To realise the potential of the project, many more voices need to contribute and represent the full scope of queer Australian art practice. As Jack Halberstam has asserted,

[the] archive is not simply a repository; it is also a theory of cultural relevance, a construction of collective memory, and a complex record of queer activity. In order for the archive to function it requires users, interpreters, and cultural historians to wade through the material and piece together the jigsaw puzzle of queer history in the making.[6]

This reflexive approach to activating stories often hidden away in drawers or on shelves is one element of the project we are most excited by. Yes, we want a book on queer Australian art, because why isn't there one? And we will make one. But in working towards this long-term goal, we will also seek to push the potential of a centralised space that holds onto the complex and unstable formation of queer culture whilst directing and connecting to the wealth of resources that already exist. We envision that queeraustralianart.com might become a marshal of sorts, centralising the art and artists, as well as writing and exhibition projects, both historical and in the present.

Communities that live in the margins of society have long been ignored by mainstream collecting practices, and therefore archives. In his article Orders of Value: Probing the Theoretical Terms of Archival Practice, Brien Brothman states that ‘the order that archives create out of all the information they process is an order that embodies society's values.’ He uses the metaphor of “weeds” as a way to address the elements of society that disrupt the normative/accepted parts of this “garden” of values.[7] How might this metaphor be applied to specific archives such as, for example, Artlink’s own publication history? How has queer practice been represented within the pages of this magazine over the decades, and what gaps or trends does the coverage of queer art reveal? Artlink was established in 1981, and was originally published as a bi-monthly, stapled edition in black and white. Between 1988 and 2020 it was released as a quarterly magazine (droppint to three annual issues in 2021). Since 1989, these have been thematic issues, often with specialist guest editors. Over the years it has published hundreds of texts dedicated to exploring aspects of Australian contemporary art, socio-political, and art historical content. In the 1990s, Artlink published articles on lesbian desire and the impact of the AIDS crisis, however, despite the increased visibility for queer theory and queer discourse in that decade, dedicated discussions of queer exhibitions and works are still thin on the ground. As Sasha Grbich notes in surveying the early Artlink issues from 1981 to 1989, the only mention of anything queer (a term Davila notably resists) was Chilean-Australian artist Juan Davila’s “homosexual erotics”.[8]

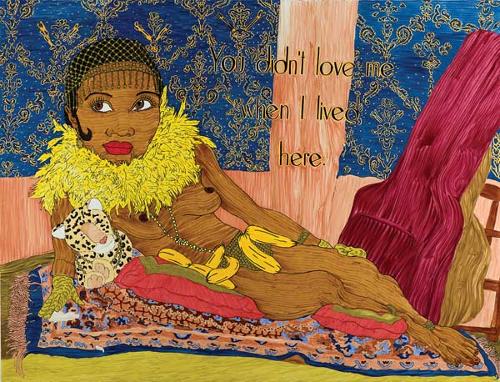

In our own preliminary survey of Artlink’s archival content over the years, there are 27 texts published between 1988 and 2022 that have a primary focus on queer art, as listed chronologically at the end of this essay.[9] The first of these was by Elizabeth Grosz in 1988, a thinker well known for her work in feminist scholarship and gender theory. Scrolling through the line-up of writers and artists over the years reveals many familiar names: Ted Gott, Russell Storer, Barbara Creed, Pat Hoffie, Barbara Bolt. The artists, too, are predominantly well-known, with feature pieces on Davila, David McDiarmid, Luke Roberts, TextaQueen, Deborah Kelly. There is limited engagement with non-binary artists or trans practice, although it appears that both male and female queer artists are given roughly equal coverage in the pages.

While the Artlink archive is not a queer archive, elements of its publishing history do partially reflect the peaks and troughs of mainstream institutional engagement with queer, lesbian and gay art over the last five decades. There is no doubt that the writers in the queer bibliography of the Artlink archive below are all scholars, curators and thinkers who have been essential in raising the visibility of queer practice in Australia. However, much more needs to be done in the field of Australian art history to stretch these aims: bringing together bibliographies of queer writings on queer artists (not by state, or by publication, or by collection, or by institution but across the whole country), while also uniting the disparate publications about queer art that are spread across multiple formats and forums and which currently occupy no shared or communal space of access. Queer Australian art's records are still limited, and correspond to waves and perhaps whims of fashion. As queer artists and scholars, we long to be surprised in these spaces, for the engagement to be sustained and not slotted into neat and predictable cultural themes or limited to discussion of only those artists whose works have already been accepted into recognisable institutional frames.

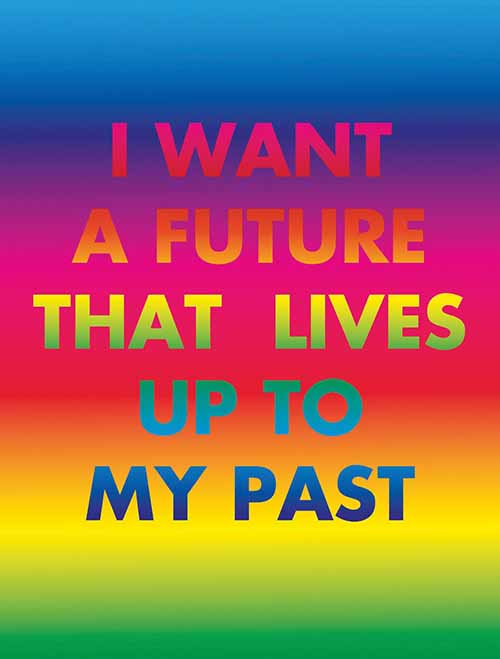

Perhaps this engagement can only exist when the weeds are more fully embraced across a spectrum of different temporal and cultural habitats? Our process for developing queeraustralianart.com has at times been murky, messy, slippery, mirroring queer lived experience. While occasionally frustrating, we acknowledge that developing a queer archive in the 21st century should not be straightforward. In part, KINK’s name originates from the image of a bent road or a kink in a hose: both linear trajectories, like conventional historical narratives, troubled by a point of difference that productively disrupts and challenges simplistic movement. Throughout the bumps, and twists and turns, we have questioned the role of the archive, the importance of both visibility and invisibility, both now and then, and the role that seeing ourselves reflected in the world has on the shaping of identity and community. At the same time, we have recognised our desire to hold identity and lived experience in a space that does not pigeonhole nor frame any individual as one-dimensional, while staying alive to the complex intersections of art, identity and politics that shape LGBTIQ+ practice, in all its diversity. Our work is done with full knowledge that queer bodies have ‘been subjected to unique and complex histories of erasure, regulation, modification, and amplification in the archives. Indeed, an enduring imperative of queer archival work has been to challenge and reconfigure the terms under which bodies and their desires have archival existences.’[10] There is still much work to be done.

Elizabeth Grosz, “Desire, bodies and representation”, Artlink, 8:1, (1988): 34–39.

Barbara Creed, “Lesbian independent cinema and queer theory”, Artlink, 13:1, (1993): 11–12.

Barbara Bolt, “Shedding skins: identity and ‘lesbian’ art practice”, Artlink, 14:1, (1994): 22–24.

Ted Gott, "Grief and the gay community", Artlink, 14:4, (1994): 16-21.

Evelyn Hartogh, “Queer Transgressions”, Artlink, 20:3, (2000): 90.

Josephine Wilson, “Jo Darbyshire: The Gay Museum”, Artlink, 23:2, (2003): 91.

Jo Higgins, “Frank Watters and Watters Gallery 42 years on”, Artlink, 26:4, (2006): 90–91.

Paul Allatson, “Juan Davila: Queering the South”, Artlink, 27:2, (2007): 16–20.

Ilaria Vanni, “Deborah Kelly’s gods, monsters and probable histories”, Artlink, 28:3, (2008): 26–30.

Alison Bechdel, “Dykes to watch out for”, Artlink, 30:2, (2010): 70–73.

Pat Hoffie, “AlphaStation/Alphaville: Luke Roberts”, Artlink, 31:1, (2011): 96.

Naomi Gall, “TextaNudes: Arlene Textaqueen”, Artlink, 31:2, (2011): 154.

Troy-Anthony Baylis, “Troy-Anthony Baylis: Queerly speaking”, Artlink, 32:2, (2012): 100–101.

Angelita Howell, “Colour by number”, Artlink, 32:4, (2012): 92.

Russell Storer, “Deborah Kelly: The miracles”, Artlink, 33:3, (2013): 46–49.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, “Body fluid II (redux)”, Artlink, 33:3, (2013): 96.

Margaret Mayhew, “When this you see, remember me: David McDiarmid”, Artlink, 34:3, (2014): 98.

Jared Davis, “David Rosetzky: Gaps”, Artlink, 35:1, (2015): 78.

Abbra Kotlarczyk, “Queer uses of colour: A tinted hermeneutics”, Artlink, 39:1, (2019): 42–47.

Sasha Grbich, “Tremble thinking: Queer monuments and counter-memory”, Artlink, 41:2, (2021): 26–33.

Callum McGrath, “Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection”, Artlink, 42:2, (2022): 101–107.

Footnotes

- ^ Daniel Marshall and Zeb Tortorici, “(Re)Turning to the Queer Archives”, in Turning Archival: The Life of the Historical in Queer Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 9.

- ^ Lennard Davis, “Criminal Statements: Homosexuality and Textuality in the Account of Jan Svilt:”, Narrating Transgressions: Representations of the Criminal in Early Modern Europe, ed. Rosameria Lortelli and Roberto di Romanis (New York: Peter Lang, 1999), 85.

- ^ Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the 19th Century”, New Left Review, Issue 48 (March 1, 1968): 84.

- ^ Marshall and Tortorici, 9.

- ^ Marshall and Tortorici, 10. Emphasis added.

- ^ Jack Halberstam, In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 292–93.

- ^ Brien Brothman, “Orders of value: Probing the theoretical terms of archival practice”. Archivaria, 32: 81 (1991).

- ^ Sasha Grbich, email to authors, 16 November 2022.

- ^ Artlink is currently upgrading its database and website as it undergoes full digitisation of its archive. We anticipate more comprehensive search results across all our content soon – Editor.

- ^ Marshall and Tortorici, 8.