%20-%20Alick%20Tipoti(2).jpg)

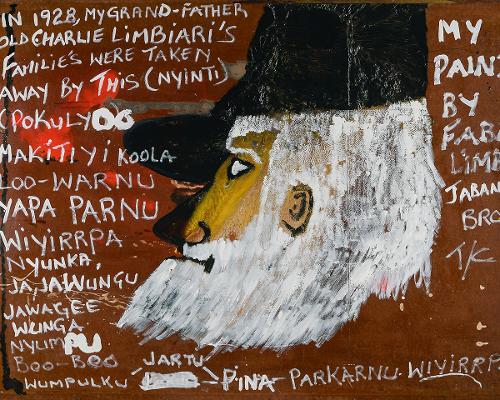

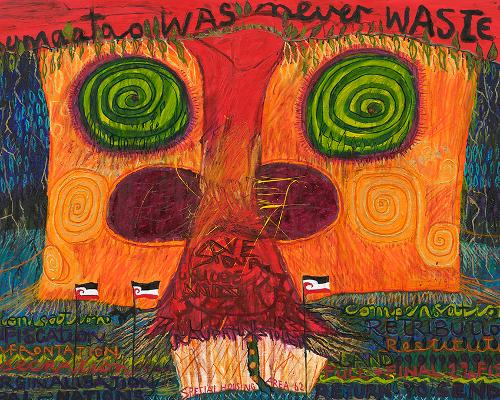

Taking over three galleries of the City Hall Wing of National Gallery Singapore (NGS), Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia is being billed as ‘the largest’ and ‘the biggest’ exhibition of its kind to travel to Asia, but it is not the first.[1] Curated by Tina Baum, it presents material familiar to contemporary Australian audiences which prompt reflection upon the centuries-long mistreatment of Australia’s Indigenous peoples: the colonial occupation of unceded land, broken promises, nonextant treaties and continuing inequities. But the collection in the context of NGS introduces a dialogic framework which integrates the museum’s historical former Supreme Court and City Hall Buildings, both landmarks of Singapore’s colonial past and its journey to independence. A collaboration with NGS, Ever Present serves to connect Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art with Southeast Asia in a form of cultural and political diplomacy—albeit carefully sanctioned—in which each country has their own distinct histories and master narratives, with parallel but different degrees of marginalising individuals and communities based on ethnic, political, gendered, sexual or otherwise divergent identities.

What radical potential for changing attitudes does the modern art museum still hold? The NGS, intended to champion Southeast Asia’s and Singapore’s art, may find Ever Present an opportunity given the urgent need to challenge the complex condition of contemporaneity in the face of political upheaval in many Southeast Asian countries in recent times. Unfortunately, the humane concerns and radical potential of the exhibition is partially overshadowed by the immersive power of the NGS architecture. The wide brutalist corridors, staircases, terraces, doorways and columns make little allowance for joy, spirituality or human emotions. The most jarring occurrence of the formula comes when one enters the former courtroom of the Chief Justice, which is overlooked by state portraits of royalty, and which is the venue for the gallery’s permanent display of Southeast Asian art, subtitled Between Declarations and Dreams. It’s an ambition of the NGS to engage with Indigenous Australian artists in this context too, where Mervyn Bishop’s Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into hand of traditional landowner Vincent Lingiari, Northern Territory (1975), is subordinated to the surrounding walls of protocol, and the crushing weight of the nation state and its politics. Nearby is Minang/Wardandi/Bibbulmun artist Christopher Pease’s Wrong side of the Hay (A deserted Indian village) (2005) which depicts the violent dispossession of the Nyoongar people from their lands during the colonial settlement of Australia. This work is juxtaposed, somewhat incongruously, with Raden Saleh’s monumental history paintings of lions and tigers, Juan Luna’s large, romantic-style oil paintings of ‘beautiful solidarity’ between the Philippines and Spain, and other idealised rural landscapes in Southeast Asia. Even Richard Bell’s well-travelled Embassy, (2013—), an installation which re-enacts a key part of the Indigenous political struggle in Australia since the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was first installed in the national capital in 1972, seems consumed by its surrounds.

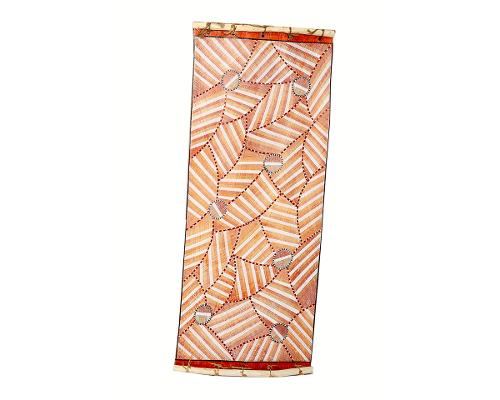

Drawn from the collections of the National Gallery of Australia and The Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, the works in Ever Present share many similarities with the developments of contemporary art from Southeast Asia. For example, the artists’ desires to embrace the vernacular and the approach placed on both ‘the People’ and their suffering as primary sites for resistance against colonialism, nationhood, national identity and modernity. Furthermore, Southeast Asia as a region has countless dimensions of cultural diversity and myriad forms of art and ideology. These differences straddle native traditions, widespread animist myths and Indigenous beliefs and knowledge as well as the religious and philosophical practices of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islamic and Christian teachings. In its syncretism and material variety, Southeast Asian art mirrors the diversity of the First Peoples Art of Australia.

While Alick Tipoti’s Koedal Baydham Adhaz Parw (Crocodile Shark) Mask (2010) is an important component of ceremonies in the Zenadth Kes/Torres Strait Islands, FX Harsono’s use of the mask is representative of Javanese culture, symbolically questioning power relations in Indonesia. While the Pitjantjatjara Ken sisters’ Yaritji Young, Maringka Tunkin, Sandra Ken, Freda Brady and Tjungkara Ken wow audiences with their delightful folksy depiction of Kungkarangkalpa tjukurpa (Seven Sisters dreaming) fleeing heavenward to escape the advances of an old sexually predatory man, Thawan Duchanee cleverly invokes a re-examination of ethnicity in Buddhism by highlighting the traditional art of the Indigenous peoples of Thailand. In video work, Waanyi artist Judy Watson chronicles the names of sites across Australia where massacres of Aboriginal people have occurred since European colonisation. On a different scale, Le Huy Tiep’s figurative expressionism deals with the traumatic event of the Vietnam War and its aftermath. Redza Piyadasa questions the basis of modern art and the mentality of the nation itself in Malaysia, while Lee Wen’s performance as Yellow Man explores yellow skin as a signifier of racial and ethnic difference.

As elsewhere in the world, art has served as a catalyst for nationalist struggle in much of Southeast Asia, and has simultaneously been deployed by the state as part of a nation-building strategy. Singapore ceased to be a colony of Britain and moved to become part of Malaya in the 1950s, only to separate from Malaysia to become a sovereign and independent nation in 1965. In his book Singapore: its Past, Present and Future, Alex Josey commented that ‘What Dr Goh and other Singapore leaders forgot to say, when speaking of the opening up of Singapore as a trading centre, is that the colonialists were the Chinese and the Indians, not the Europeans. The Europeans were the imperialists.’[2] A provocative statement, it argued the importance of the Chinese and the Indian populations during the nation-building years. It draws parallels with Bidjara artist Michael Cook’s Undiscovered series (2010) in which an Aboriginal man in colonial navy uniform standing on the shore, poses the question: Who really discovered Australia? Like the Chinese and the Indians, seen as Indigenous populations in early Singapore, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are foundational to Australia’s heritage, its development and its postcolonial history.

During the mid-twentieth century nation-building years of Singapore, local artists reflected on their involvement in the decolonisation struggles and searched for innovative ways to depict its new nation status and their own identities and subjectivities. The artists were also beginning to take in the variety of experiences made possible by modernity, and many held sceptical views of modernising in the 1960s. The various ideas came through in works currently on display at the NGS by Chua Mia Tee whose Epic Poem of Malaya (1955) and National Language Class (1959) are iconic examples. Yeh Chi Wei whose commitment to primitivism and the Indigenous peoples of the region such as the Dayaks are equally bound up in the idea of an inclusive model of nation-building. Other themes include Goh Beng Kwan’s work whose art extolled the virtues of ‘Asian’ traditions and Singaporean culture, while Anthony Poon heralded the modern in cityscapes and urban living. These Singaporean works also spoke to the centrality of nationalist culture in Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art during the decades of political upheaval.

Ever Present contains a rich cross-section of works by more than 150 artists, from the past 100 years or so. Its six sections ‘Ancestors + Creators’, ‘Country + Constellations’, Community + Family’, ‘Culture + Ceremony’, ‘Trade + Influence’ and ‘Resistance + Colonisation’ attempt to represent Orientalism as a contemporary problem, and a reality that promotes the difference between the familiar and the strange. It reveals the psychology of the Indigenous people who were essentialised as irrational, depraved, gullible, while white Australians were rational, virtuous, mature. One will find the theme of torture in the work by Yhonnie Scarce, of Kokatha/Nukunu/Mirning peoples, her depiction of blown glass bush fruit being grasped by metal forceps drives home the facts of pain and abuse. To the imagined Singaporean viewer, the initial response may be mild shock, quickly replaced by distance and passivity. Could it be that Singapore is too perfect, too protected by the state or too comfortable—at least for a typecast and typical museum-visiting, middle-class audience? Meticulously governed, the city-state is also clean, green, orderly, efficient, and almost perfectly safe. A prominent disclaimer is displayed in none-too-small print on the NGS’s Ever Present landing page:

The National Gallery Singapore respects the diverse points of view of all artists and speakers in this exhibition. The views and perspectives expressed by them are their own and may not reflect the position of National Gallery Singapore.[3]

The difficulty of arousing a Singaporean audience is to some extent induced by the nation state in its pursuit of excellence. Furthermore, tensions between the state which prioritise business and economics against human rights issues (such as homosexuality and censorship), are ongoing realities. Artists such as Tang Da Wu, Lee Wen, Amanda Heng, Suzanne Victor, Vincent Leow, and others engage in ‘alternative’ strategies such as performances and installation art that can be characterised as critical of conservative Singapore society. For example, Josef Ng’s Brother Cane (1994) performance exposing his buttocks and cutting his pubic hair protested the arrests of twelve men for homosexual solicitation and the perceived imbalances in the news coverage of the arrests.

.jpg)

The juxtapositions of the histories and art of Southeast Asia and the First Peoples of Australia highlight difficult issues while including a strident individualism, a penchant for change, and an engagement with criticism. Even though Europeans violently invaded Australia and Southeast Asia, even though the currents of social conflict and cruel injustice persisted, the recovery of the self and of autonomous dignity prevail, despite the ongoing legacies and continual variations of global colonisation.

Footnotes

- ^ Between 1974 and the early 1980s, The Aboriginal Art Board (as part of the Australia Council) toured 19 exhibitions of Indigenous art to over 40 countries, including African and Asian nations, Papua New Guinea and New Zealand. See Nina Berrell, Inroads offshore: The international exhibition program of the Aboriginal Arts Board, 1973–1980 https://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_4_no1/papers/inroads_offshore#Endnotes%2026-50

- ^ Alex Josey, Singapore Its Past, Present and Future (London: Andre Deutsch Limited, 1980), 21.

- ^ See https://www.nationalgallery.sg/everpresent