Maumau tangata, maumau whenua: Waste the land and you waste the man: On the work of Emily Karaka

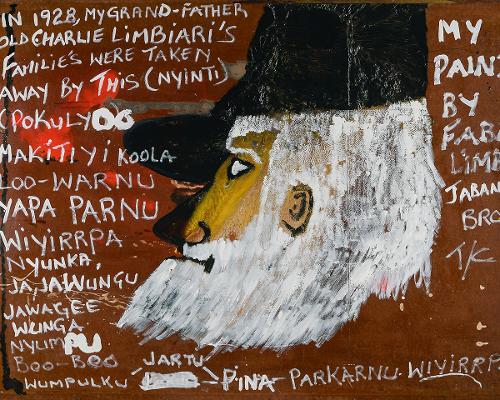

Three large wood panels depict a body splayed across the pictorial plane. These bodies appear Christ-like, each laid across a crucifix. The panels form a triptych and echo early mediaeval religious painting traditions, but the paint is smeared and gestural. Each panel represents a different deed: the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi (New Zealand’s founding agreement between the Crown and Māori); the 1952 ANZUS Treaty, a defence pact between Australia, New Zealand, and the US; and the 1977 Gleneagles Agreement opposing sporting contacts with apartheid‑era South Africa. These three documents are indicated at the top of each panel and were designed to ‘protect’, but are depicted as torn, smudged, and signed in blood. On a separate painting on hessian, a ‘nuclear mother’ confronts us in the far left of the panel. Around each cross is painted the famous 1864 battle cry of Māori leader Rewi Maniapoto (Ngāti Maniapoto), declared during the New Zealand land wars: ‘Ka whawhai tonu matou, ake, ake ake’, which roughly translates to: ‘We will fight against you forever’.