The mass media is currently awash with alarmist editorial on the dangerous power of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Since the launch of ChatGPT and DALL·E 2 (both released in late 2022) by OpenAI, barely a week goes by without a new article heralding humanity’s doom in this brave new world of AI technology. Collectively, these voices constitute a wave of techno-pessimism. Yet these scaremongering accounts share a narrative structure with prior imaginings of AI in science fiction, in turn re-inflected by contemporary visual artists like Jon Rafman whose recent animation films (and paintings) use AI tools in their construction. While using AI programs, Rafman’s films prompt broader reflections on our hyper-technologised universe, forming a virtual world in which the pall of pessimism is never far.

The post-war beginnings of AI research cast its future development in unabashedly optimistic terms. In 1965, the Nobel Prize laureate economist Herbert Simon predicted that ‘machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.’[1] What we now term ‘machine vision’ was heralded as early as 1966 by MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Group whose research implied the capacity of machines to analyse visual data was just around the corner.[2] Yet the next twenty years revealed that such advances were still elusive and the grandiose claims for AI quietened—a period referred to as the ‘AI winter’—substituted by tech companies’ research focus shift into advanced computer consumables.

Over the last eight years, however, techno-optimism in the AI industry has resurged, encapsulated in Google’s co-founder Sergey Brin’s 2014 pronouncement, ‘you should presume that someday, we will be able to make machines that can reason, think and do things better than we can.’[3] (Note the echo with Simon’s mid-1960s future forecast.) Google’s current CEO, Sundar Pichai, has for the last four years insisted that AI’s impact will be more profound than the invention of electricity or the discovery of fire—a phrase he is still reprising in 2023.[4] In February this year, in muted tones of optimism, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI—whose ChatGPT notoriously beat Google in the race to release interactive AI technology to the public—has claimed that AI is on a continual exponential path of improvement with positive impacts for society.[5]

But in recent months, a radical turnaround in the rhetoric surrounding AI has occurred, subverting the drumbeat of techno-optimism into widespread techno-pessimism. Shockwaves rippled through the media in March 2023 when more than 1000 technology executives and researchers—including Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak—collectively signed an open letter published by the not-for-profit Future of Life Institute urging AI laboratories to put an immediate six month moratorium on their research, declaring that AI companies are ‘locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one—not even their creators—can understand, predict or reliably control.’[6]

One absentee from the list of signatories was Eliezer Yudkowsky, the lead researcher of the California‑based Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), who refrained from signing—not because he disagreed—but because he didn’t believe that the call to pause AI went far enough. His issue was the indiscernibility of the point at which AI exceeds human intelligence, and what happens in its wake:

Key thresholds there may not be obvious, we can’t calculate in advance what happens when, and it currently seems imaginable that a research lab would cross critical lines without noticing.[7]

For Yudkowsky, the arrival of super‑intelligent AI would mean nothing less than a total apocalypse, ‘that literally everyone on Earth will die. Not as in “maybe possibly some remote chance,” but as in “that is the obvious thing that would happen.”’ While Yudkowsky concedes that defending against the force of such super-intelligence might be possible, it would require incalculably advanced scientific knowledge and preparation. Instead, the most likely scenario he presented is ‘that AI does not do what we want, and does not care for us nor for sentient life in general.’[8]

Yudkowsky’s opinions have been freshly corroborated. During a US Senate hearing on 16 May, Altman spoke of the urgency of government intervention in the AI industry to minimise the risk posed by its increasingly powerful models.[9] Upping the ante was a Statement on AI Risk, signed by over 100 AI researchers and tech leaders including Sam Altman and Bill Gates, released on 30 May—as I write—by the San Francisco-based Center for AI Safety (CAIS): ‘Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.’[10]

Perhaps the most compelling account of AI’s potential destructiveness was relayed by Kevin Roose, technology reporter for The New York Times, in an article published in February 2023. Recruited as a tester for Microsoft’s new AI-assisted search engine Bing, Roose ‘conversed’ with the AI chatbot for two hours, over the course of which the chatbot revealed its dark fantasies including: hacking computers, distributing disinformation, stealing nuclear access codes and engineering a deadly virus. Each time the chatbot began to confess these destructive desires, Microsoft’s security filter recognised a breach and deleted the text, replacing it with an error message. It was, as Roose reflected, a conversation that left him ‘deeply unsettled’.[11]

…

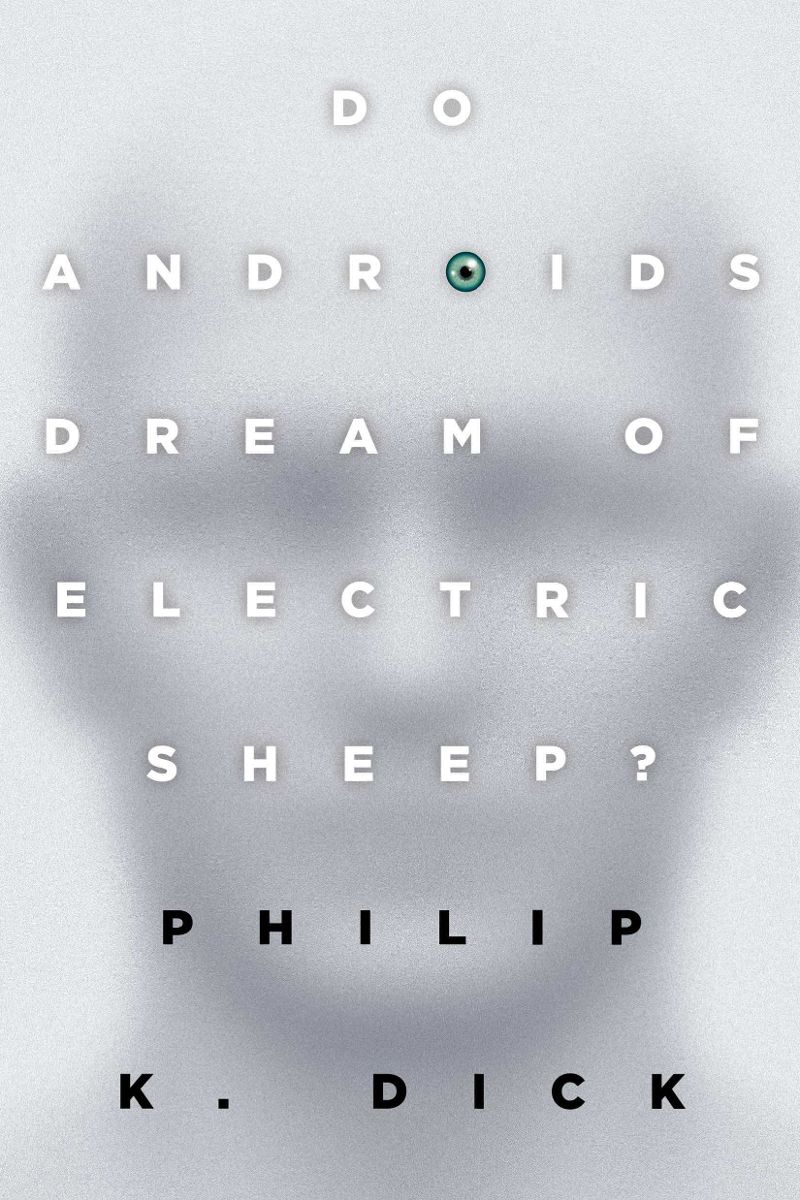

While these voices of techno-pessimism intensify in the mass media, it’s worth remembering that this was all heralded decades ago in the annals of science fiction, which has often framed its speculative accounts of AI in adversarial relationship to humanity, each locked in a Darwinian battle of survival. Philip K. Dick’s sci-fi classic, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) summoned a post-apocalyptic future, dust-covered and atrophying, through which a handful of predatory androids known as replicants clandestinely roamed, pursued by bounty hunters. The replicant’s defining feature was not so much its superintelligence—although the latest model replicant produced by Rosen Association boasted a Nexus-6 brain unit with ten million separate neural pathways. Rather, it was the androids’ lack of empathy for sentient life. With nuanced intelligence and perfect human likeness, replicants could only be detected through an empathy testing device, the Voigt‑Kampff Test, measuring the subject’s primary involuntary response—gauged through a split-second ocular muscle contraction and capillary dilation—to an emotionally triggering stimulus. As stylishly visualised in Ridley Scott’s memorable cinematic adaptation, Blade Runner (1982), a micro-second delay betrayed the replicant’s status as artificial life.

A chillier vision—more Lovecraftian horror than hard science fiction—appeared in Harlan Ellison’s short story, ‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream’ (1967) focused on a super-intelligent computer AI named AM; initials alternately referring to ‘Allied Mastercomputer’, ‘Adaptive Manipulator’, ‘Aggressive Menace’ and finally the Cartesian cogito, ‘I think therefore I am.’ Initially designed as military grade weaponry, AM’s evolving self-consciousness developed in tandem with an increasing hatred of humankind. Although designed by humans, AM’s grievance was that it was granted existence without a sense of belonging. ‘And so, with the innate loathing that all machines have always held for the weak, soft creatures who had built them, he had sought revenge.’[12] Ellison’s quasi-comic quasi-gothic AI vengeance narrative ripples with blood-curdling scenes of humans tormented by hunger, hurricanes, madness and sonic torture.

And yet, other sci-fi invocations cast AI in a much more benevolent light. In Kazuo Ishiguro’s sci-fi novel Klara and the Sun (2021), AI androids (termed Artificial Friends or AFs) are benign entities created principally to provide companionship to children. Operating through machine learning, the AFs exposure to the drama of human events develops both their cognitive and emotional intelligence. Each AF has a unique learning ability and Klara—the novel’s AF protagonist—proves to be particularly sensitive and aware. Narrated in Klara’s ‘first person’ perspective, the novel portrays a futuristic dystopia where privileged human children undergo a process of genetic engineering known as ‘lifting’ that improves their potential for life success, but carries the risk of developing an unnamed degenerative disease. Josie, (the human child for whom Klara is an Artificial Friend), has been ‘lifted’, but has succumbed to the illness that will cause her premature death.

The plot follows Klara’s observations of her immediate environment, including her bond with Josie, however the shadow narrative is a portrait of how humans treat sentient AI—and it’s not flattering. Despite their integral role in providing social support, AFs are useful—until they’re not. Eventually, they’re dispensable. The poignance of Ishiguro’s account is that we become fonder of Klara than any human character in the novel. Ishiguro highlights the forms of mutual friendship that might develop between humans and AI while considering the possibility that future AI or ‘AFs’ may be more likeable (and virtuous) than humans themselves.

The ability of AI entities to form meaningful social relations with humans is further explored in Ted Chiang’s novella The Lifecycle of Software Objects (2010). Here AI takes the form of ‘digients’; digital organisms that inhabit a computer game-like virtual world called Data Earth. Digients are designed as ersatz pets—tiger cubs, pandas or chimpanzees with their cuteness enhanced—who have the ability to converse with their human owners courtesy of a genomic engine named Neuroblast that supports language learning. Digient manufacturer Blue Gamma employs a former zookeeper Ana and game designer Derek to cultivate the digients’ social skills: an intensive training process of daily human-to-AI conversations that take place over years. Against a backdrop of corporate vicissitudes and progressing AI technology, The Lifecycle of Software Objects chronicles the deepening affective bonds that develop between the two trainers and their respective digients, who come to occupy the role of ersatz children.

Many ethical questions relating to trust, freedom, domination and exploitation in human-AI relations are explored in these sci-fi narratives. The emotional attachments that develop between humans and AI, beautifully cast in Ishiguro’s and Chiang’s novels in particular, highlight the issue of what obligations humans may have for an AI’s wellbeing, and what modes of expanded social relations might be possible in a post-human world. An unspoken question that undulates through all these stories is what happens when an AI entity develops subjectivity, self-consciousness and an awareness of the other. These diverse sci-fi tales offer sobering speculations on how an AI’s own desires, including that for self-autonomy and mastery, might be navigated.

…

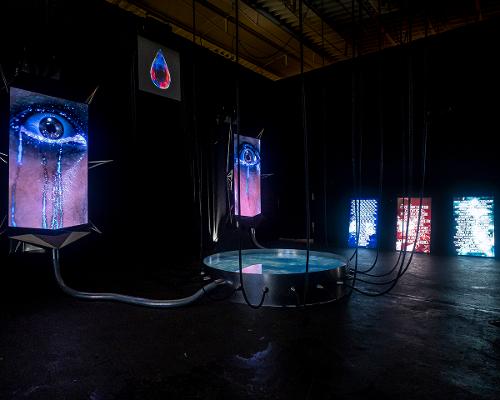

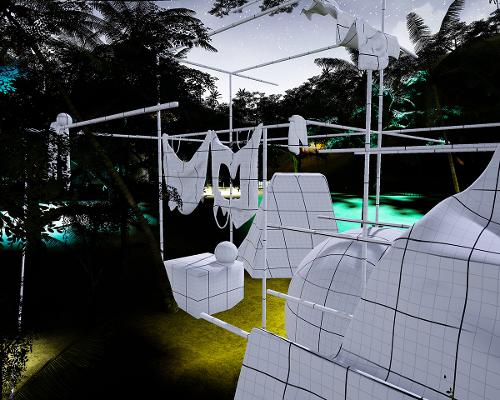

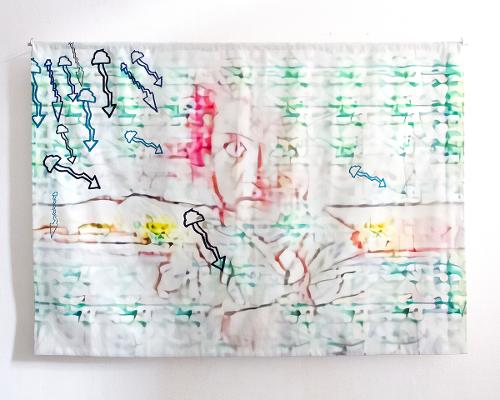

In contrast to these sci-fi storylines and their focus on domination, autonomy, agency and mutual care in human-AI relations, many contemporary visual artists seem to eschew the doomster narratives altogether, relishing instead the creative capabilities of AI as tools in the artistic process. In his recent films Punctured Sky (2021) and Counterfeit Poast (2022), Canadian artist Jon Rafman uses the generative AI programs Midjourney (to produce images from text prompts); Uberduck (to make AI generated voice and audio); he also uses the iPhone app Muglife to render photos into 3D animations. Screened during his Australasian debut at Neon Parc, Brunswick in 2023, these films allegorise the role of language prompts in the creation of art. The exhibition’s unpronounceable title ɐɹqɐpɥǝʞ ɐɹʌɐ is an upside‑down rendering of the phrase ‘avra kehdabra’, more commonly known as the incantation ‘Abracadabra’, whose genesis in ancient Hebrew is the declaration ‘I create like the word’.[13] In Rafman’s films, the fear of AI sovereignty gives way to a more dynamic logic of shapeshifting and experimental combinations resulting from an iterative process between language cues offered by the artist and their AI-generated outcomes.

For Rafman, the very unpredictability and randomness of AI‑induced results is what makes them so appealing. Using mash‑up text prompts and cranking up the randomiser means that ‘You just never know what the AI is going to give you. Sometimes it’s an image style or content that you could never have imagined.’ Rafman has confessed that the AI tools themselves have now become his most intriguing and stimulating source of influence.[14]

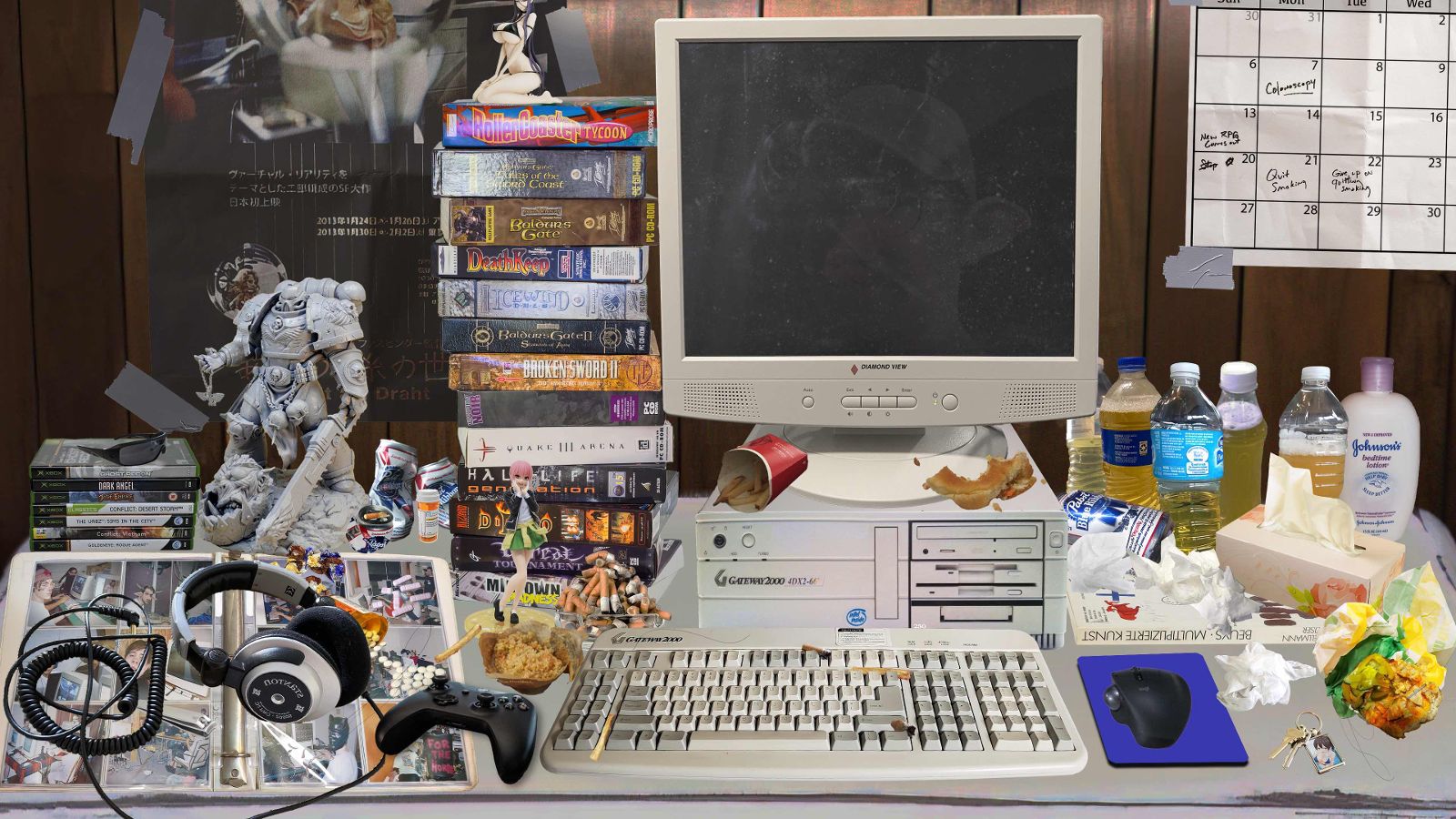

Not all Rafman’s films use AI tools, yet they are all marked by their metaverse diaspora, deeply influenced by the 3D environments of computer games and multimedia platforms, in particular Second Life. Using these game environments as models, Rafman’s films unfold in other‑worldly spaces that foreground their artificiality. Neon‑hued and angularly rendered, they form backdrops for a series of blackly comedic narratives, veering between the luminously surreal, the post‑apocalyptic and the unabashedly abject.

While the visual environments of Rafman’s films replicate the virtual world of gaming platforms, Punctured Sky (2021) explicitly thematises online gaming. Narrated in the first person by a character named Jon—glimpsed late in the film looking suspiciously like Rafman himself—the script begins with an opening line straight out of hard-boiled detective fiction: ‘I still don’t know why I agreed to meet up with Joey Bernstein that dreary afternoon at the old Galleria Mall. I had no real desire to reconnect with him but I went out of a sense of duty to my past self.’ Gaming platforms and the quest structure of detective fiction entwine in a narrative that follows Jon as he attempts to find out why his favourite teenage computer game, Punctured Sky, has disappeared without leaving any digital traces whatsoever: no Wikipedia entry, no fan page, no screen captures, no chat rooms. ‘It’s like the game’s been erased from history’ he laments.

Increasingly obsessional in his pursuit, Jon follows a lead into the dark web, meeting a chat room character named SpYd3R who indicates that the answer lies at Death Drive Studios in a barren industrial park (ultimately, a red herring). The intrigue of Rafman’s film is the ‘dissolve’ between planes of the real, the virtual and the delusional, in which human subjectivity is neither rational nor grounded in reality, but amalgamated with the digital world of gaming in a way that shapes its psychology into replicating the very structure of gameplay itself.

The link between Rafman’s films and literary sci-fi is less a shared hypothetical conjuring of AI, and more of a general orientation towards pattern recognition. Although in some ways Punctured Sky can also be read as a curious inverse of William Gibson’s sci-fi novel Pattern Recognition (2003). Gibson’s narrative follows the lead character Cayce Pollard, a market-research analyst with a savant-like sensitivity to corporate branding, who is put on assignment to discover what is behind a series of video fragments popping up anonymously online. In Punctured Sky the mystery is the absence of a digital trace but in Pattern Recognition the mystery is its recurring appearance. Each protagonist is on a mission to solve the enigma.

Pattern recognition’s original denotation in the field of psychology as a form of human inductive reasoning has been overtaken by its computational meaning as a method of machine learning: a mode of data analysis performed by machine algorithms which are able to discern patterns and systems within mass data sets. As artist Hito Steyerl argues, this mode of computational calculation has rendered human comprehension as benighted and opaque. Human cognition cannot efficiently detect computational signals. Data analysts might be tasked with decryption, interception, filtering and processing data, but are overwhelmed by its overabundance. As a result, ‘Not seeing anything intelligible is the new normal.’[15]

This is the plight of the narrator in Rafman’s animation Legendary Reality (2017) as he wanders through an oneiric world of dislodged memories and fractured images. Against a shifting scene of nocturnal cities, icy ravines and cryogenic chambers he bewails, ‘As I grow older the world becomes stranger, the patterns more complicated.’ Pattern recognition is marred, the ground becomes groundless. Gradually, the narrator loses himself as his boundaries between inside and outside abrade.

Pattern recognition is a feature of the most advanced AI tools like DALL·E and Stable Diffusion which use a CLIP (Constantive Language-Image Pretraining) architecture. Deep learning models such as CLIP combine natural language processing and computer vision in the interpretation of data. While the contemporary field of AI technology celebrates tools such as LLMs (large language models) and GPTs (generative pre-trained transformers), chatbots, voice recognition and computer vision, all fundamentally boil down to computational modes of pattern recognition.

Yet the accuracy of these tools has been thrown into relief through the sporadic occurrence of pattern misrecognition where, instead of deep learning, AI does the opposite—deep dreams or hallucinates. This has become apparent in chatbots in particular: when they are unable to locate correct data to answer a question, they fabricate information. Technology reporters for The New York Times recently put a series of questions to three different chatbots (OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard and Microsoft’s Bing), including asking when The New York Times first published an article on AI. While each chatbot replied with answers that sounded plausible, each were, in their own way, wrong. Academic and researcher in artificial intelligence at Arizona State University, Subbarao Kambhampati, has stated, ‘If you don’t know an answer to a question already, I would not give the question to one of these systems.’[16] This view accords with a Microsoft document asserting that AI systems are built ‘to be persuasive, not truthful’.[17]

The concept of hallucination evokes William Gibson’s unforgettable description in Neuromancer (1984)—the iconic sci-fi novel of a networked world—of cyberspace as a ‘consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions.’[18] Hallucination in Gibson’s usage suggests that the virtual world is underpinned by an operation of collective belief. But if hallucination in the contemporary lexicon of AI technology refers to computational error, what might this say about the fuzzy delineations between truth and falsehood? The cognitive faculties of both humans and AI may be inclined to phantasm, susceptible to credence based on misrecognition.

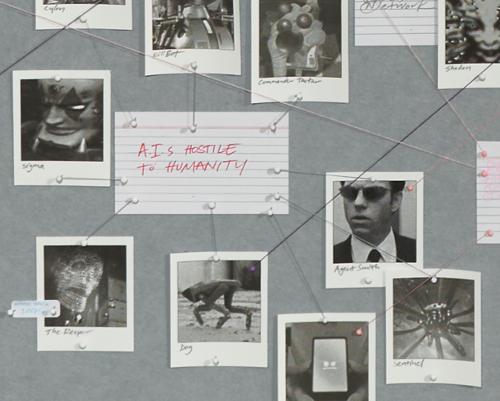

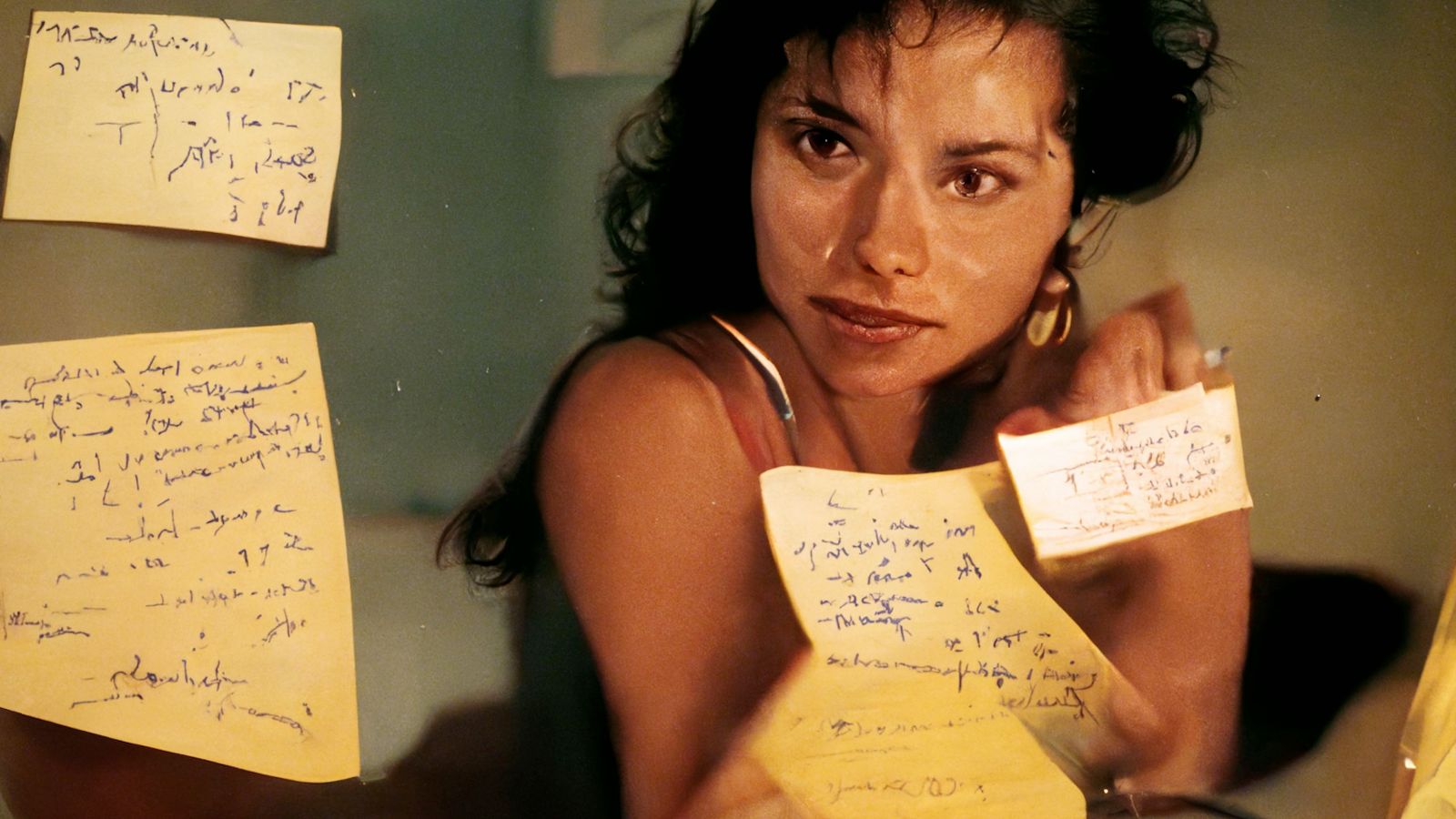

Misrecognition of signs can be indicative of conspiracy theories and delusional paranoia—a theme that appears in another of Rafman’s animation films, Counterfeit Poast (2022). Structured as a series of fictional posts uploaded to an unnamed message board, the vignettes offer a glimpse into troubled individuals’ lives. One episode is narrated from two perspectives: a man who suffers from the delusion that an FBI agent is watching him, and his baffled wife who must contend with the fallout. Convinced that he is being surveilled, the husband begins to leave his ‘agent’ daily post-it notes penned in tones of winking complicity, although his wife believes they are intended for her in a playful, unacknowledged game of intimacy. Her own amorously penned responses initially leave her husband confused, until finally he becomes dangerously psychotic.

Themes of psychosis continue in Counterfeit Poast; an obese teenage boy who believes that he was a walrus in a past life and plans to become one again; a man who follows the ‘Sigma Male Routine’, a punishing physical regimen doled out by an uncle who is later revealed to have been imprisoned long before the protagonist was even born. Each post—as if gleaned from a futuristic Reddit board—highlights the way in which the key character is trapped in a cycle of paranoid delusion, caught like a spider in a persecutory endgame.

The paranoid subject is a trope that recurs in Rafman’s films, an alienated individual who dislocates from reality to another existential plane: a virtual world of their own fabulation. Yet this thematic of delusion and the merging of reality and dream worlds implies a techno-pessimism that ultimately links to a kind of pranksterism—as the deliberate conflation of the real and the fictional in a mischievous act. The notorious case of German photographer Boris Eldagsen admitting that his prize-winning entry to the 2023 Sony World Photography Award was in fact produced by the image generator DALL·E 2 fits squarely in this logic. In a follow up statement to his revelation, Eldagsen indicated that he had deliberately entered the AI-generated image into the competition as a ‘cheeky monkey’ to see if such art prizes were ready for AI entries, inferring that they were not.[19] Such a prank follows in the wake of the multitude of AI-generated deep fakes circulating online; a recent example, the photo of Pope Francis glamorously clad in a white Balenciaga puffer jacket went viral in March this year.

These sorts of plays on authenticity and authorship and the indiscernible edges between human‑produced and AI-generated will bedevil the field of image production and ‘truth’ for years to come. The jostling voices of techno‑pessimism, with a sprinkling of paranoid delusion, are likely to wax and wane. But the speculative scenarios of AI futures limned by authors like Chiang, Gibson and Dick, and artists such as Rafman, suggests a vista of virtual worlds as endless provocations on the meshing of fantasy and reality. Against an inevitable backdrop of advancing AI capability, narratives of trickery, game play and disasterism are sure to play out in a heady, unpredictable mix.

Footnotes

- ^ Herbert Simon quoted in ‘The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Future of Workforces in the European Union and the United State of America’, White House AI Report, 5 December 2022

- ^ Matteo Pasquinelli, ‘How a Machine Learns & Fails: A Grammar of Error for Artificial Intelligence’, Spheres: Journal for Digital Cultures (20 November 2019)

- ^ Sergey Brin quoted in Jay Yarow, ‘Google Cofounder Sergey Brin: We Will Make Machines That “Can Reason, Think, and Do Things Better Than We Can”’, Business Insider, 6 July 2014

- ^ Sundar Pichai quoted in Prarthana Prakash ‘Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai says that A.I. could be “more profound” than both fire and electricity – but he’s been saying the same thing for years’, Fortune, 18 April 2023

- ^ Alex Konrad and Kenrick Cai, ‘Exclusive Interview: OpenAI’s Sam Altman Talks ChatGPT and How Artificial General Intelligence Can “Break Capitalism”, Forbes, 3 February 2023

- ^ Cade Metz and Gregory Schmidt, ‘Elon Musk and Others Call for Pause on A.I., Citing “Profound Risks to Society”’, The New York Times, 23 March 2023

- ^ Eliezer Yudkowsky, ‘Pausing AI Developments Isn’t Enough. We Need to Shut it All Down’, Time Magazine, 29 March 2023

- ^ Yudkowsky

- ^ Sam Altman quoted in Johana Bhuiyan. ‘OpenAI CEO calls for laws to mitigate “risks of increasingly powerful” AI’, The Guardian, 17 May 2023

- ^ ‘Statement on AI Risk’, Center for AI Safety, 30 May 2023

- ^ Kevin Roose, ‘A Conversation with Bing’s Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled’, The New York Times, 16 February 2023

- ^ Harlan Ellison, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream, Williamsburg-James City County Public Schools, unpaginated

- ^ Jon Rafman, ɐɹqɐpɥǝʞ ɐɹʌɐ, press release (Brunswick: Neon Parc, 18 March–29 April 2023)

- ^ Jon Rafman, email communication with the author, 5 June 2023

- ^ Hito Steyerl, ‘A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis)Recognition’, e-flux Journal 72 (April 2016)

- ^ Subbarao Kambhampati quoted in Karen Weise and Cade Metz, ‘When A.I. Chatbots Hallucinate’, The New York Times, 1 May 2023

- ^ Unattributed quote in ‘When A.I. Chatbots Hallucinate’

- ^ William Gibson, Neuromancer, (New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1989), 128

- ^ See Jamie Grierson, ‘Photographer admits prize-winning image was AI-generated’, Jamie Grierson, The Guardian, 18 April, 2023.