%202018_watercolour%20and%20gouach%20on%20tracing%20paper.jpg)

Tucked inside the left wing of Queensland University of Technology Art Museum, Pat Hoffie’s This Mess We’re In seems to speak to our immediate historical moment: the failed Indigenous Voice to Parliament Referendum, warnings of an impending El Niño and another blazing summer, and new waves of media footage showing atrocities committed by Israeli forces against civilians in occupied Palestine. The irony is, Hoffie’s ‘mess’ (in a nod to Samuel Beckett)[1] is a much longer documentation, across four series and a decade (2009–2020) of the artist’s prolific and sustained practice. Each provides a unique response to the white noise of disaster, chaos, and suffering characterising the world of our times.

The exhibition begins in a museological vein. Upon entry, a collection of small works on paper—seemingly ripped from the artist’s sketchbook—rest in a glass vitrine like souvenirs from a mysterious or metaphysical pilgrimage. In these pictures, human legs protrude from the mouth of a giant green fish while elsewhere two figures carry the body of a third, wrapped in a white cloth. White substances rain down from fighter jets, smoke billows from a small barbeque, explorers stand on a craggy outcrop, and a naked man urinates on a strange reptile. These images of more-than-sentient beings in real and unreal landscapes are neither complete nor preparatory, but rather seem possessed of a strategically provisional quality.

Adjacent to the vitrine is Ready to Assemble (2009), a series of carefully selected juxtapositions rendered in muted shades of white and grey on coloured paper. Diagrams from IKEA furniture construction manuals and grids of pegboard polka dots float among images of military tanks, toy aeroplanes, astronauts, and surgeons. Here and there, lovely animals, children, and creatures in various states of reciprocity offer reprieve, but pools and clouds and spills of ink signal an ever-present threat: the loss of control. For the artist, this aesthetically restrained series is like a compendium of achievements and setbacks: they are partial glimpses and speculative observations in which the boundaries between real and imagined, humour and horror, cooperation and conflict are seemingly dissolved and an almost faith-like reverence for the spirit and process of adaptivity is established. For the viewer, this antechamber functions like an amuse-bouche for the epic frieze-like compositions awaiting in the gallery’s main spaces.

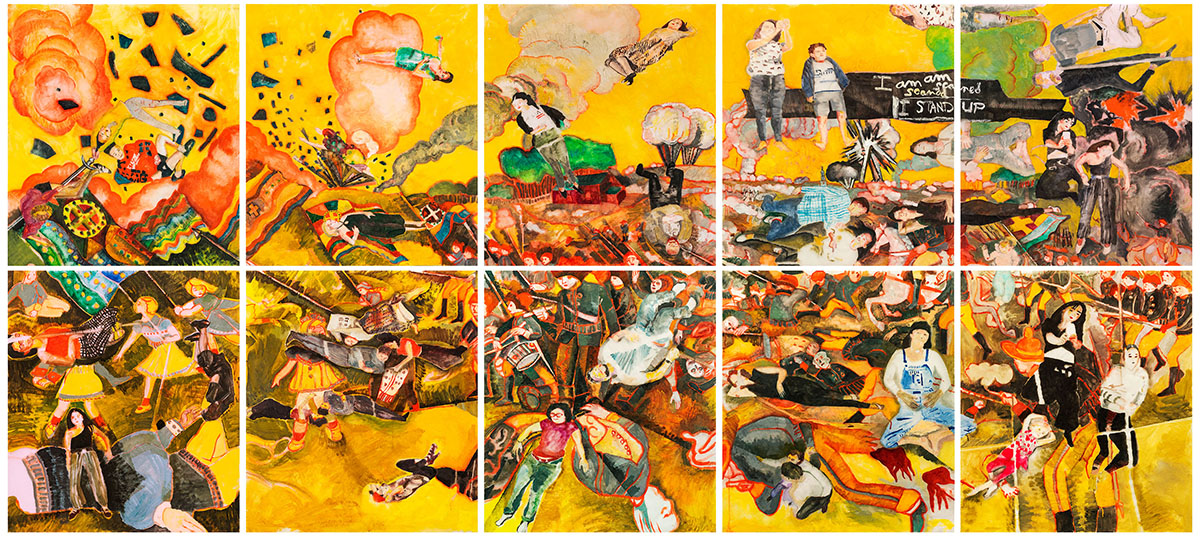

The central series Clusterfkkk, (2018–2020) approximates the colloquial term for a complete failure, or an utterly disordered mess, the artist’s neologism alluding to the American white-supremacist terrorist organisation, the Klu Klux Klan. Like Ready to Assemble and the provisional sketches, Clusterfkkk brings together an awesome array of disparate references, mashed together across ten large-scale watercolour and gouache paintings on architects’ paper (tracing paper). In Reconstitution (2018), Henry Darger’s ‘Vivian Girls’[2] (and the figures of more contemporary young’uns) can be seen running across the lawns of Parliament House which flies a tiny Aboriginal flag. In Civil War (Constructivist Combat Drones) (2018), a swarm of soldiers wielding guns, swords, and batons fill the centre of the composition. Winged three-dimensional shapes in Russian Constructivist red, black, and white float overhead through lightning and laser beams while others of their kind lie in rubble among dead bodies underneath. From a nearby tree, the Vivian Girls watch on, now wearing the African masks appropriated by Picasso in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907).

Hoffie borrows from literature, pop culture, and art history in this way not for stylistic effect nor as an ode to Australian art’s tendency toward revisionism. Rather her appropriations reflect the breathless flow, the endless circulation of ideas, images, and objects within networks, their ‘transitivity’[3] as David Joselit puts it. By situating these appropriations amongst references to people, places, and things from her own life (a trademark of her work since at least the 1990s), Hoffie reveals a porous membrane between private and public worlds, between official and unauthorised testimonies.

The material qualities of the Clusterfkkk paintings defy reproduction with their fragile surfaces of floating pigment and chalky luminescence. The large sheets of tracing paper, pieced together to resemble a unified field of vision, are held to the wall with small magnets, yet no attempt has been made to disguise the pieced together, almost modular, nature of these compositions. The gaps are visible between the sheets, some corners curling away from the wall. This internal rupturing seems a critical part of the series. They feature compositional devices and iconography typical of historical paintings by Bruegel, Goya, Picasso, and Diego Rivera, while simultaneously conjuring the spectre of contemporary war photographs which, as Judith Butler suggests, work as instruments in the solicitation, recruitment, waging, and storying of war.[4] Hoffie coaxes these erstwhile antithetical modes of representation into her picture planes, fracturing them as a means through which to question not just the nature of images and the realities they represent and produce, but also the politics of looking at images of conflict.[5]

The final dimly lit room hosts Smoke and Mirrors (2016), a collection of charcoal and ink works on paper of barely visible boats navigating—or succumbing to—terrifying expanses of spilled black ink. This tragic series inspires a profound sorrow in me, which I sit with for a time, before turning away, turning back to I am Scared/I Stand Up (2018). Here, the distinctive figure of the artist in elegant black garb can be seen taking photos on her iPhone around a central battle scene replete with flags, explosions, plumes of smoke, shards of obliterated things, and more Vivian Girls. In the top right-hand corner, white text on a black background reads ‘I am scared, I stand up’ (a reference to the painting Scared (1976) by the New Zealand modernist Colin McCahon).[6] The quote goes to the heart of This Mess We’re In which attempts to process and give form to the fallout of late-stage capitalism, climate chaos, racially and religiously motivated violence, global disaster and disease. The exhibition showcases Hoffie’s lifelong compulsion to respond to the world around her through creative action. It also reveals the slow and deliberate witnessing that art, in particular painting, is unique in facilitating.

Footnotes

- ^ Samuel Beckett cited in Tom Driver, “Beckett by the Madeleine,” Columbia University Forum, no. 4 (Summer 1961): 23

- ^ The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion by Henry Darger, is an illustrated fantasy novel manuscript discovered after Darger’s death. Imagery ranges from idyllic fantasy to horrific torture and carnage.

- ^ David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130 (Fall) 2009: 125

- ^ Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (London: Verso, 2009), xii

- ^ A topic covered at great length by Susan Sontag in her 2003 text Regarding the Pain of Others.

- ^ Brisbane/Meanjin artist Gordon Bennett (1955–2014), once a student of Hoffie’s, also appropriated McCahon’s Scared (1976) in his painting, Angry (1993).