Photo: Kate Land

We are greeted by three modest-sized black-and-white photographs on a black wall. They’re all the same scene, a tree in a rough clearing which has a section of portable fencing around it. They present slightly shifting perspectives on the scene. There is no descriptive wall text for these works and the program notes don’t particularise the scene.

This is how we enter Alana Hunt’s Surveilling a Crime Scene, with a sense of repetition and disorientation. The tree-triptych is but one of the exhibition’s nine discrete spaces realised through three film-based works, three large-scale drawings and around 50 mostly black-and-white photographic prints of varying scale arranged in series or individually. Despite the lack of wall text, the show is text-abundant with words playing a central role in the films and works on paper. It's a significant accretion of work.[1]

There are however two paragraphs of wall text about the exhibition so we come to know the “landscapes” depicted are of Gija and Miriwoong Country in and around the township of Kununurra in north Western Australia. Though they’re not all landscapes. Some photographs show interiors or are poised in close-up at the entrance to singular buildings—worksite demountables, the colloquial dongas. As with a crime scene, the image-scapes seem to be mostly off-limits to the contaminating presence of humans. We are left with only ghostly remains to unpick the evidence.

People are not wholly absent. Within a grid of twelve black-and-white photographs we see a group of tourists boarding a ‘river cruise’ power boat. They are generalised, seen from the back and mostly from a distance. It could be any group of tourists on any day in Kununurra, an overt reference to the exhibition’s stated subject in the ongoing colonisation of Miriwoong Country. Here we have the landscape colonised as tourist commodity for the consumption of faceless tour groups. The bus pulls in, the tourists alight, board a boat and take to the water as part of an assembly-line Kimberley “experience”.

Photo: David Hancock

People are also present through voice. In the gallery’s screenroom Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven (2020–21) plays (black text on white), narrated by Sam Walsh, a former CEO of mining giant Rio Tinto. In official-sounding monotone, Walsh reads out the titles (purpose summaries) of 967 Section 18 applications made between 2010 and 2020, each simultaneously appearing onscreen. Section 18 applications are made to override the Western Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act (1972)—in effect, a state-legislated licence to ‘destroy, damage or alter an Aboriginal site.’ (The exhibition notes reveal that only about three of the 3,300 such applications since 1972 have been denied.) The knowledge of Walsh’s participation lends both absurdity and authority to the exercise, a fine line which persists throughout the exhibition. Walsh’s narration is the inspiration for Hunt’s three spirited text-based drawings A Very Clear Picture (2020) in the same room, while an entire Section 18 application informs In Plain Sight (2023), a film-based work in another room. Here each word of the application has been dissected and rearranged alphabetically as hand-debossed text on 67 sheets of paper, each becoming a film still. Unfortunately, on both occasions I visited the exhibition this film was stuck on a single frame. While its idea was apparent the force of the film’s painstaking language conceit was missing.

The most prominent audio voice in the exhibition comes from Hunt as she narrates her centrepiece film from which the exhibition takes its title. Projected cinematic scale, the 22-minute film is shot in Super 8, that quintessential medium of the amateur, the tourist. Like Walsh’s narration, Hunt’s voiceover is superfluous, as the words she speaks appear as text (in a no-nonsense, black-outlined yellow font), yet the audio plays an important humanising level of reinforcement (even with Walsh’s monotone delivery). Hunt by contrast speaks with a gentle, probing pointedness. Her delivery is spacious, pausing for effect, allowing the footage to also speak for itself. This text-narration is a rich blend of facts and commentary chronicling the history of pastoral grabs in the region (namely through the Durack and Forrest dynasties) and the push for development leading to the much lauded and heavily subsidised Ord River Irrigation Scheme of last century. Citing the scheme’s steep imbalance between investment and return, Hunt surmises, ‘The colony is a welfare recipient / always was, always will be.’ Elsewhere she mentions the great dream of a Kimberley food bowl culminating with the inedible sandalwood tree. Her deft economy of words undercuts.

Photo: Maurice O'Riordan

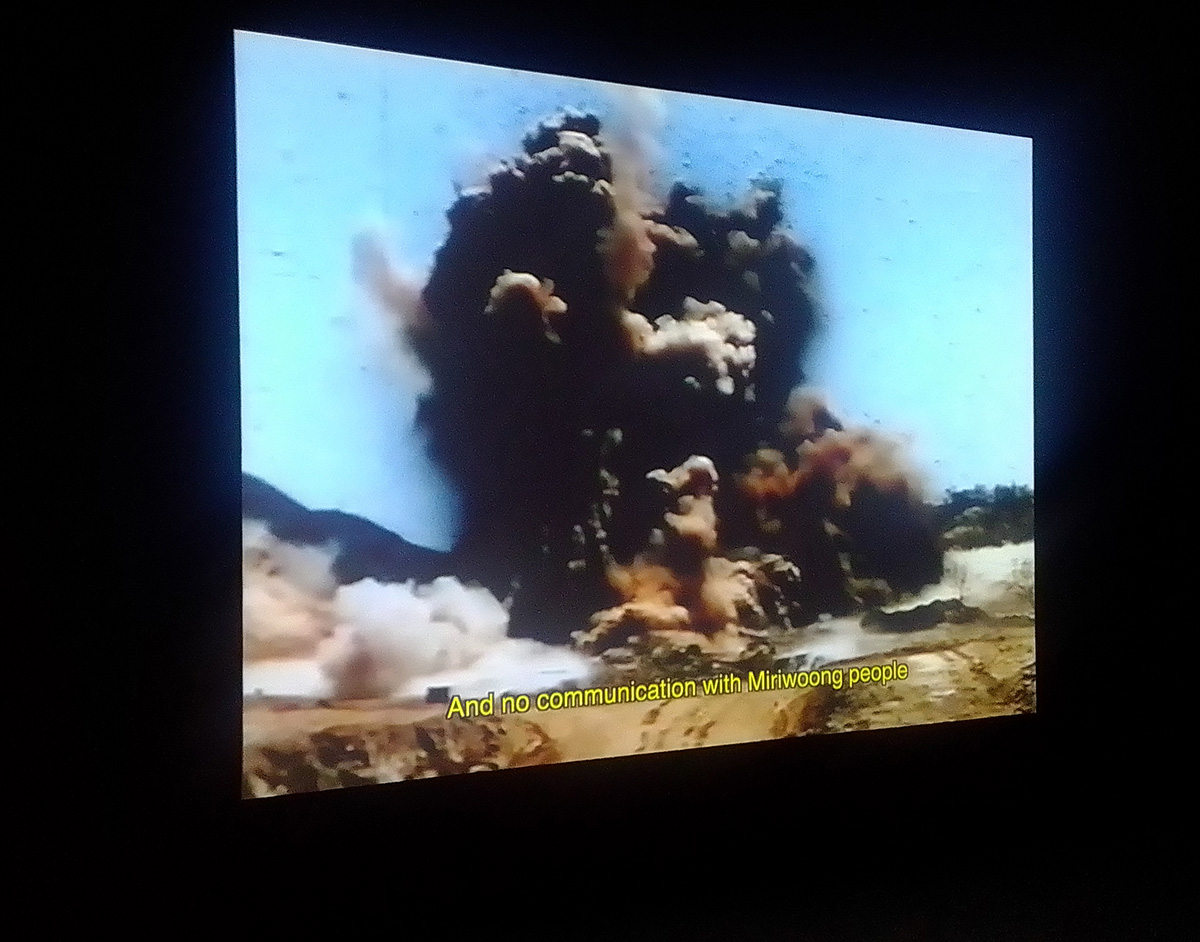

People inhabit this film directly and indirectly, a presence implicit in the construction of the Kununurra Diversion Dam in 1963 and the subsequent birth of Kununurra township. Hunt’s narrative also contains riveting archival footage of the blasting of Miriwoong Country in 1970 to make way for the Ord River Dam and Lake Argyle reservoir completed in 1972, the year WA’s Aboriginal Heritage Act came into being. Unsurprisingly, Miriwoong people didn’t figure in any consultation. After all, it had been only a little over a decade since the neck-chaining of Aboriginal people (including children) in the Kimberley was banned, a practice largely driven by pastoral expansion.[2]

In the film, the blasts play out a silent apocalypse yet Hunt doesn’t linger too long in the past. Her sights are trained on the omnipresent crime of the fitness enthusiast, those who delight in the Lake’s leisurely pursuits (“the boat people”), who careen around Kununurra bike tracks revelling in easily accessed “wilderness”. It’s a banal, everyday sort of violence, this unexamined love of the great outdoors enjoyed at the expense of Miriwoong custodianship and heritage. In a town where the police station and courthouse loom tallest, ‘Everyone’, says Hunt, ‘talks about stolen cars and not about stolen country.’

Aesthetically this film impresses, slipping between ultra-grainy and documentary-plain, between black-and-white and colour-saturation. The imagery spills beyond the frame’s edge and at times spools out as though catching its breath from the enormity of transgressions both tragically absurd and incessant. The soundtrack opens with kitsch Western movie-style instrumentals and at turns plays a brooding, sombre drone.

Surveillance might infer forensic-level examination with exacting details about location, time, persons of interest. This exhibition’s surveillance is not so inclined. While I do want to know the significance of the tree in the triptych and other documentary details not in the program notes, there is a power in the generality of the exhibition’s approach, in suggesting the ubiquity of the crime. Visually the exhibition commands its own strong and stirring logic. There is a power too in the steadiness of Hunt’s gaze, turning on the antics of her own culture-of-colonisers rather than seeking redemptive attachment through Miriwoong eyes, and not to belittle the work’s reliance on various levels of local Aboriginal involvement. ‘How the sediments of that time seep into the present / into things / into us’, Hunt narrates. We are all implicated.

Post the hope for a ‘yes’ in the 2023 referendum that uttered a ‘no’ (to an Indigenous voice to parliament and Constitutional recognition), this exhibition lays bare the intellectual apathy and indifference of an enduring colonial, racist body politic.

Footnotes

- ^ The exhibition draws on several bodies of work: Faith in a pile of stones (2018); Violent Dreams of Development: A Food Bowl in the north-west of Australia (Artlink, 2019); All the violence within / In the national interest (2019-21); and A Very Clear Picture (2021-23). It is accompanied by a risograph-print flipbook based on the Super 8 film Surveilling a Crime Scene.

- ^ See, for example, Chris Owen, “How Western Australia’s ‘unofficial’ use of neck chains on Indigenous people lasted 80 years”, The Guardian, 7 March 2021.