.jpg)

The real world, to Barbara Hanrahan, was the one that flourished inside the all-female household she grew up in. As she pushed through their green glass front door, she would shed her shoes and tunic, and joyfully slip into her wilder self.[1] This month, passing through the front door of Murray Bridge Regional Gallery provides a rare opportunity for immersion in the wild world Hanrahan inhabited and shared. The touring iteration of the Flinders University Museum of Art’s ambitious survey exhibition, Bee-stung lips: Barbara Hanrahan works on paper 1960-1991, exhibits 74 of the 180 works initially hung in FUMA’s major retrospective of her work. Even reduced for tour, the exhibition feels dense. The remarkable vibrance of her screen-prints exceed their printed reproductions, and taken with intricate etchings and bold linocuts, articulate the possibilities of a radically inter-connected way of being.

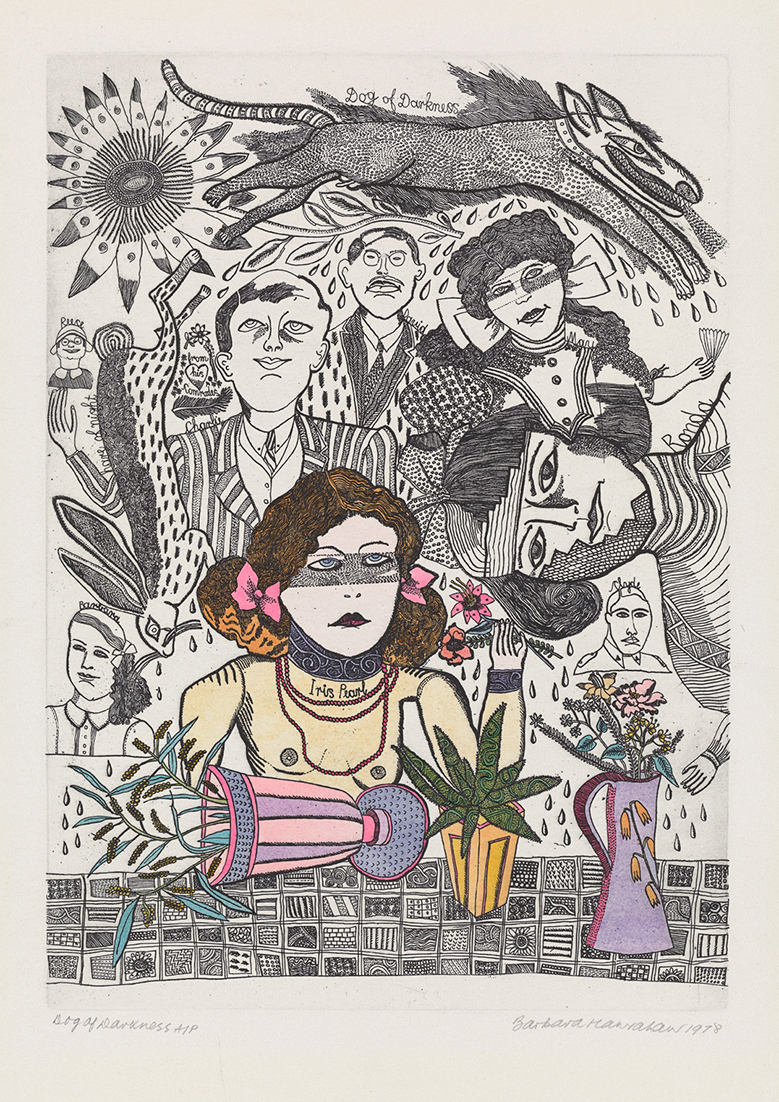

The touring iteration involved the practical necessity of removing some larger and smaller works, resulting in a selection predominately made after Hanrahan's return to Adelaide from the UK and in the second half of her too-short life. Alison Carroll’s suggestion that Hanrahan’s post–1975 period is typified by the elegance and intensity of pictorial details is confirmed by the exhibition.[2] The prints chosen overflow with interconnected, permeable people (often gaggles of ancestors); they become strata in crowded undergrounds, float close to the sun, or are held by densely drawn airs. Murray Bridge Regional Gallery has paired Bee-stung lips with an exhibition of new work by Adelaide artist Monika Morgenstern whose luminous glass and pigment works explore human desire for mystical manifestations, their exhibition in parallel bringing emphasis to the more earthy spirituality in Hanrahan’s prints.

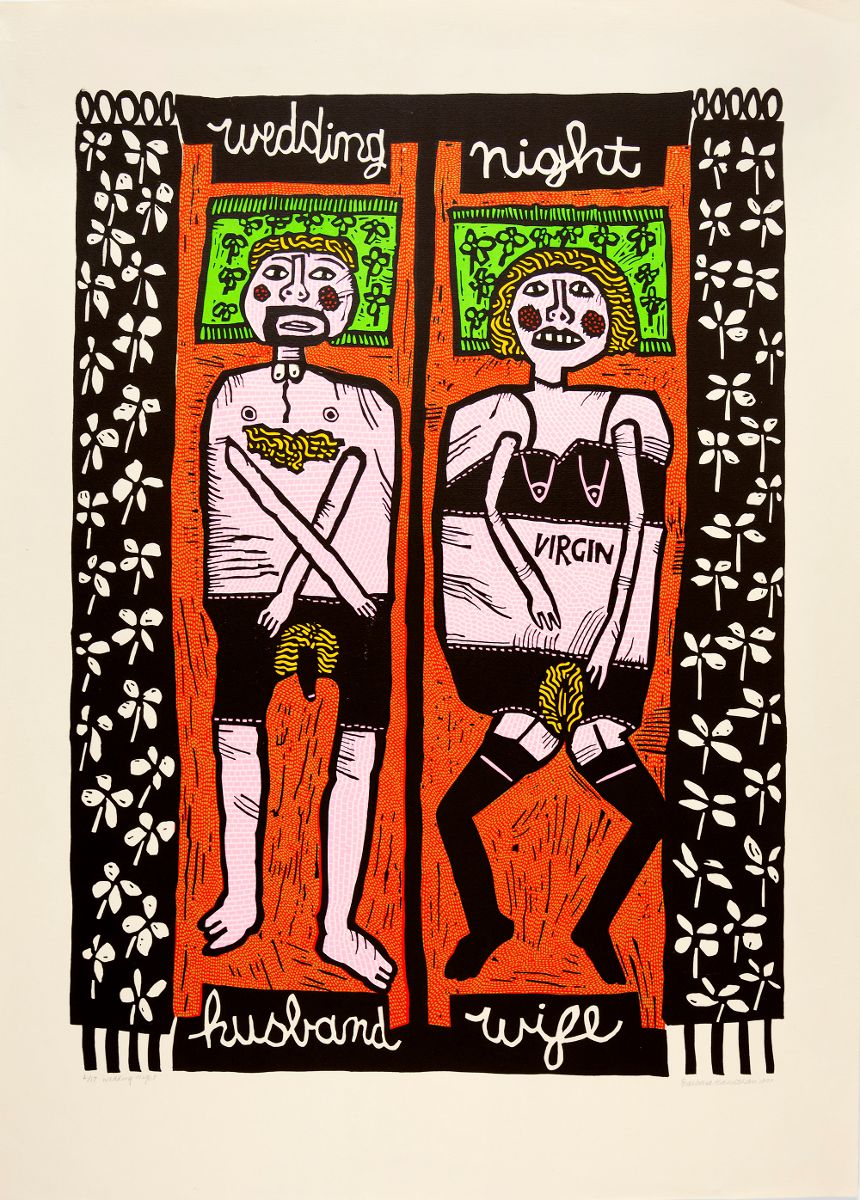

In the accompanying publication Jacqueline Millner observes that the vulvas in Hanrahan’s works look remarkably contemporary.[3] Hanrahan’s uncompromising view of female nudity casually underscores the social relations playing out between the figures who birth, marry, fuck, fly, care and congregate. The vulvas are many, and are dotted around the room, patterned with the repeatedly carved marks, one is so heavy and full-some that it looks like a bag slung casually on the sitter’s thigh. Genitals emanate through clothing, as if to point out the absurdity of hiding them away in the first place and reminding us of their ever-present politics. This is a socks-on, crotchless-pants world, which Millner characterises as ‘Brugelian carnivalesque’ wherein cycles of life, death, desire, and disgust spin, dancing vertiginously. [4]

Thinking of vulvas, a connection is made to contemporary artists including Hannah Raisin, whose absurdly funny pubic hair billows operatically in the wind in her performance work Flowing Locks (2007) and I suspect that the intricate, many-breasted worlds that Del Kathryn Barton creates must be somewhere close by. Hanrahan’s work was made amidst that wonderful, much needed 'affront to masculinity' provided by Vivienne Binns’ 1967 exhibition at Watters Gallery (which included now famous work Vag Denns (1967) and its less-celebrated companion piece, Phallic Monument (1966)).[5] In comparison, Hanrahan’s depictions of sexual power coexist with tender representations of women's lives, and in this regard, the sincere and uncompromising female-centric storytelling of filmmaker Jane Campion and the early works of Helen Fuller also come to mind. Digging in the Flinders University library I unearthed a thesis analysing sexuality in Hanrahan’s work written in the early 1990s by Adelaide artist Pru La Motte (weaver of heavy, tactile, women-parts) locating a forgotten node in a local genealogy of visceral depictions of female bodies.[6] A celebrated novelist with fifteen books to her credit, Hanrahan also contributed to articulating women's art histories. Writing for Artlink in the 1980s, her review of a major touring European printmaking exhibition brought Margret Preston’s works into relation with international currents.[7]

The book accompanying Bee-stung lips is not the first publication on Hanrahan, but is an important addition as it considers the cultural urgency of the works, where previous publications lean more heavily on biographical frameworks. Both Nic Brown and Jacqueline Millner write her work into conversation with new materialist entanglement, and in so doing, find a theorisation in which Hanrahan looks determinedly current. There is something a little clean in the becoming-plant and becoming-animal of Deleuze and Guattari, and the action flows of anthropologist Tim Ingold. Soaked as Hanrahan’s world is in the pleasures and violence of absorbing and expelling bodies, her contribution to entangled ways of being offers the flowering of messier relationalities.[8] Her sustained attention to her ancestors emerges with further destabilising force, their intergenerational inter-connection standing guard against static notions of identity and time.[9] Elspeth Pitt completes the theorisation of Hanrahan with her essay bringing forward that ‘made ecstatic by the beauty of nature’ via Hanrahan’s sustained absorption in the work of William Blake.[10]

%20(1).jpg)

Hanrahan’s work is best encountered (as FUMA has understood) as a dense collection. To see prints singularly, or scattered sparsely through larger collections, would miss the powerful experience of entering Hanrahan’s entangled oeuvre. The recent success of the project at the Ruby Awards 2022 winning in the category ‘Outstanding Work or Event Outside a Festival’ acknowledges the work done to platform women's knowledges made marginal by collecting practices past. The time and careful labour required to put such an exhibition together, extensively from private collections, is indicative of a need for further institutional purchasing.[11] Bee-stung lips turns with the possibilities of Hanrahan’s richly relational worldbuilding—and it is exhilarating to encounter—perhaps because her exuberant knowledge is still dearly needed.

Bee-stung lips: Barbara Hanrahan, works on paper 1960-1991, curated by Nic Brown, was launched at Flinders University Museum of Art (FUMA) in July 2021. The touring iteration, presented in collaboration with Country Arts SA, involves exhibitions in regional South Australia, including: Murray Bridge Regional Gallery until March 19; Port Pirie Regional Art Gallery from April; Naracoorte Regional Art Gallery from June; Riddoch Arts and Cultural Centre from September; and Signal Point Gallery from December.

Footnotes

- ^ Barbara Hanrahan, The scent of eucalyptus (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1974), 184.

- ^ Drawn from conversation with the exhibition curator Nic Brown and with reference to Alison Carroll’s biographical discussion of Hanrahan in Barbara: Hanrahan Printmaker (Netley: Wakefield Press, 1986), 61.

- ^ Jacqueline Millner makes this comment in footnotes for ”Barbara Hanrahan: Relationality, Vulnerability, Life”, in Bee-stung lips: Barbara Hanrahan, works on paper 1960-1991 (Mile End: Wakefield Press, 2021), 20.

- ^ Millner, 19.

- ^ Elwyn Lynn, “Ruffling Plumage”, The Bulletin, February 18 1967. Lynn wrote that Binns turned Watters Gallery into a “tenth-rate phallic temple” which “affronts masculinity by its challenge, makes females feel inadequate.”

- ^ Pru La Motte, “Sexuality, A Struggle in Values: A Social Semiotic Analysis of the work of Arthur Boyd and Barbara Hanrahan” (Honours thesis, Flinders University, 1989).

- ^ Barbara Hanrahan, “Rich Relief Prints: British & Australian Relief Prints, 1910 to 1950 – Art Gallery of South Australia” , Artlink, 3:6 (December 1983–February 1984): 11-12.

- ^ This is discussed by Millner via Mary Douglas’s writing on taboo and Rosi Braidotti’s posthuman feminism, Bee-stung lips, 19.

- ^ Nic Brown considers merging temporalities in Hanrahan’s work through analysis of Dog of Darkness (1978), see Nic Brown, “Time Travel, Bees and Celestial Bodies in the art of Barbara Hanrahan”, in Bee-stung lips, 4.

- ^ Elspeth Pitt, “Print, Poetry and the Romantic Imagination: Barbara Hanrahan and William Blake” in Bee-stung lips, 28.

- ^ The exhibitions have drawn from the Art Gallery of South Australia, significant lends from private collections, and the FUMA archive of Hanrahan’s work. The exhibition planning prompted new FUMA acquisitions indicating the important momentum in collecting created by such projects.