Marshmallow Laser Feast (MLF) is an artist collective who employ digital technologies to make ambitious and affecting works on ecological themes. Works of Nature at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) translates five major pieces into a cohesive installation that transports the audience from the intimacy of breath at a cellular level, to the expanded cosmology of black holes and dark matter. Intercorporeality is a core concept running throughout—a multimodal form of communication in which all bodies are porous and enmeshed within each other in the flow of chemical processes and cosmological forces.[1]

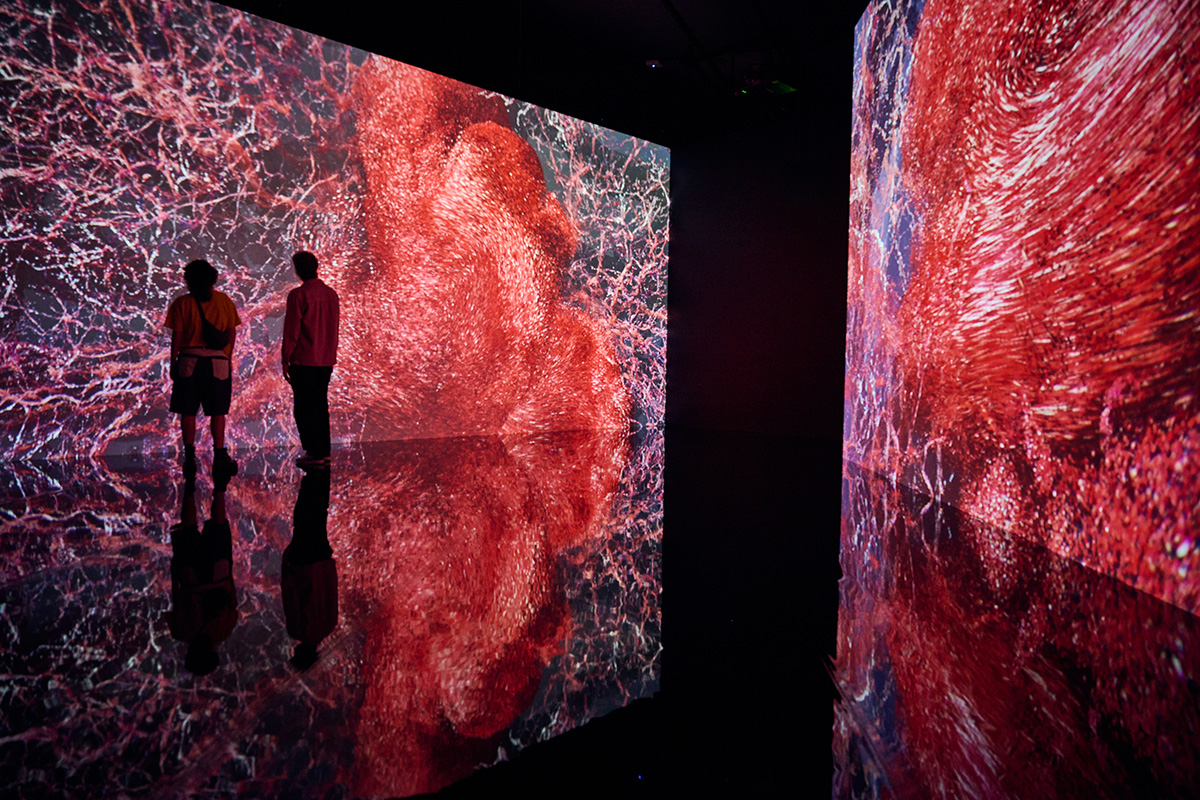

Occupying the full extent of the long, subterranean gallery at ACMI, Marshmallow Laser Feast: Works of Nature presents several works by the artist collective that leads the visitor to an encounter with a giant tree in the Amazon, the inner currents of the human body and the expanded curvature of the cosmos, leading us—and leaving us—in a final encounter with a breathing tree. The video installations stretch from floor to ceiling of the dark, purpose-built space, extended by reflective flooring that creates the impression that the images ‘pool’ below the viewer. There’s no ‘outside’, the screens enveloping us in the dynamic churn of nature that animates the ecological themes of the exhibition. Fully saturated in the experience of the work, I was also struck by the explicit invocation of awe and sublime affect, made for political ends, and left wrestling with the paradox of artists, (like myself), using polluting digital technology to invoke ecological empathy.

The central work in the exhibition, Evolver (2023) was originally developed as a virtual reality experience, an iteration of which is included in Works of Nature. The work has also been unpacked into a series of immersive video installations and an impressive sound work. This ten-minute audio piece, composed by Daisy Lafarge and voiced by Cate Blanchett, is presented as a deep meditation. It is this work that communicates the overall thesis of the exhibition most directly:

Is it possible to say where you end and begin?

When you think of the inside of your body,

What do you see? A darkness, an absence, a diagram?If we could learn to see differently

We might see that we are whirlpools:

Eddies and ripples in the vast flow of life.The atmosphere is a co-creation of all breathing beings,

you only exist in relation to everything else.

The trees, mycelium, bacteria, pollinators, oceans

are as much a part of you as your own body.If you could explore yourself, you would discover

that just below your skin you are a branching being

made of currents and rivers, the world flows into you

and you flow into the world. [2]

Text and words play an integral role in the exhibition. The walls are covered with carefully crafted poetic invocations of transcorporeality, written by Lafarge, interspersed with didactic explanations of core concepts and themes within the works. Examples include informative educational explanations of the process of respiration, the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide within the body, complemented by the inverse process with plants, the symbiotic exchange that is central to the exhibition.[3] The final section includes documentation of how the works were made, and extensive acknowledgements of the many contributors and collaborators, including scientists, required in an exhibition of this monumental scale and ambition.

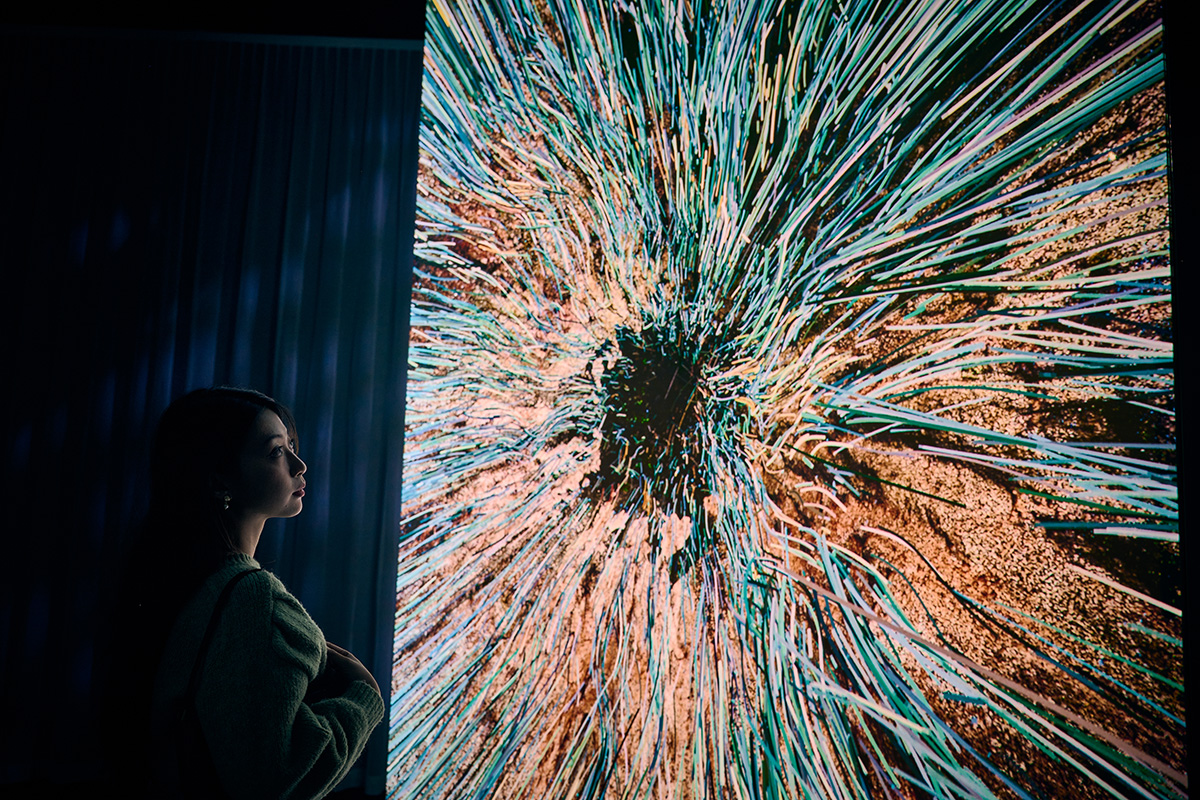

At ACMI, deeply immersed, I was curious about the ways in which the affordances[4] of our tools and technologies shape the kinds of gestures and meaning we can make.[5] Nearly all the works here have been rendered as point-clouds, a file format that represents 3D objects as clusters of data-points within three-dimensional space. This file format, which renders a topographical surface as a porous membrane via points of colour, has been widely adopted by landscape architects and has had a transformative impact on that discipline, provoking a fundamental reframing of the practice in terms of the capacity to visualise an entire site.[6] In recent years, this file-format has been adopted by artists and creative technologists fascinated by the affordances of the point-cloud and the metaphorical potential of its aesthetics. The point-cloud file format lends itself to both the meta and micro. Through this aesthetic form we encounter the cellular in Evolver and We Live in an Ocean of Air (2021), but also the cosmological scale of the universe in Distortions in Spacetime. The visual qualities of the point-cloud—its glitches, shimmering particles and dissolving, unstable structures—works here to unify the themes and intentions of the exhibition; the metaphorical potential of the technology is realised in affectively dramatising the porous flow of ecological systems.

The awe and sublime affect I was first impressed by has an empathetic tone. Unlike Richard Mosse’s Broken Spectre (2018–2022),[7] which invoked the spectacle of terror and cataclysmic catastrophe of deforestation in the Amazon, Works of Nature evokes wonderment and kinship with our symbionts. As the wall text explicitly puts it, the evocation of awe for political ends is intentional, notably citing the ‘overview effect’ when astronauts first viewed our planet from space, and related a non-human centric subjectivity. The artists claim similar shifts can be achieved by experiencing ‘epic virtual landscapes or a VR journey through our own branching bodies.’ Further, they suggest that,

Experiences of awe can have a lasting effect, increasing people’s kindness and connection to nature – the only proven driver of pro-environmental behaviour. It’s a powerful transcendent state with personal, social and environmental impact.[8]

The Earthrise photograph taken by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders from lunar orbit, published on the cover of The Whole Earth Catalogue in 1969 was a milestone, imagined as an image to move humanity towards a new collective consciousness.[9] Thinking historically, I was reminded of Morning mist, Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, Tasmania (c1980) by Peter Dombrovskis, that became the icon for the Tasmanian Wilderness Society’s campaign to save the Franklin River in the 1980s. As Peter Timms remarked in 2004 of this influential photograph, images that evoke awe and the sublime are often drawing on the conservative picturesque conventions of European landscape painting. In the decades following, First Nations’ thinkers have further critiqued the false idea of ‘untouched wilderness’ and conservationists aims to preserve ‘wild nature’. However, in Dombrovskis image, the affective power that drew on the 19th century German Romantic tradition spoke powerfully to the consciousness of its time.[10]

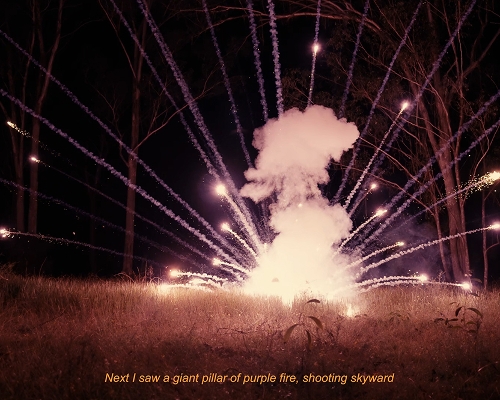

A sense of awe is also evoked in the 2023 film The Giants, about the ancient trees of the Tasmanian old growth forests and Greens politician Bob Brown. There are several spectacular sequences within the film of point-cloud representations of trees created by Alex Le Guillou from 3D forest scans provided by Terra Luma, at the University of Tasmania.[11] The clusters of glowing lights that describe 3D forms suggest a form of immanence: of the spiritual embedded in the material.

Another Australian work also comes to mind: Lynette Wallworth’s Awavena (2018). As an extension of 360-degree video footage Wallworth created with the Amazonian Yawanawá people, she made a virtual reality work experienced via a headset that enabled the viewer to ‘walk through’ a celestial forest of glowing lights. Wallworth was approached by the Yawanawá to collaborate with them, as they saw correlations between her VR artworks and their Shamanic use of visionary plant medicine. Wallworth’s work has extraordinary political impact as a regular presenter at the annual World Economic Forum at Davos.[12] Unequivocally affecting and effective at communicating the magical and transcendent qualities of the natural environment to evoke a sense of awe, however, the visual similarity between all the works discussed above invites the question: to what extent does the work rely on the affordances of this technological choice? Will these works lose impact as audiences become more familiar with the aesthetics of the point-cloud form and its immersive style of delivery?

Despite the rhetoric of the digital as dematerialised, virtual, and ‘in the cloud’, digital media is of the world, utterly physical with profound and devastating real-world impacts.[13] We know this long list of environmental destructions almost by heart: from mining rare earth minerals for digital media to the oppressive factory conditions in production, the physical cost of repetitive strain injury and sedentary lifestyle on technology’s consumers, and the energy required to render and run these works and the resulting e-waste due to built-in obsolescence. At the very least, Works of Nature is a positive use of digital media to impact humanity’s thinking towards a liveable future, achieved by evoking a sense of emotional connection and kinship—for some—with the stuff of the world.

Footnotes

- ^ Stacey Aliamo, “TRANS-CORPOREALITY” in Posthuman Glossary, eds. Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 435-439.

- ^ “Evolver: The Journey of the Breath,” (ACMI, 2023).

- ^ Large print labels, ACMI, 2023.

- ^ William Gaver, “Technology Affordances” in Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: Reaching through Technology, 27 April – 2 May 1991, 79-84.

- ^ Rosa Menkman, “Refuse to Let the Syntaxes of (a) History Direct Our Futures” in Fragmentation of the Photographic Image in the Digital Age, ed. Daniel Rubinstein (Taylor & Francis Group, 2019), 118-120.

- ^ Christophe Girot, “Cloudism: Towards a New Culture of Making Landscapes” in Routledge Research Companion to Landscape Architecture, eds. Ellen Braae and Henriette Steiner (London: Routledge, 2019),113-123.

- ^ Mosse’s work was shown at Melbourne’s NGV 1 October – 22 September 2023.

- ^ Large print labels, ACMI, 2023.

- ^ Joe Moran, “Earthrise: the story behind our planet's most famous photo,” The Guardian, 22 December 2018.

- ^ Peter Timms, “Love, Death and Wilderness Photography”, Island 97 (2004): 16-26.

- ^ “Making of the Giants” https://thegiantsfilm.com/making-of accessed 11 February 2024.

- ^ “World Economic Forum: Lynette Wallworth”, https://www.weforum.org/people/lynette-wallworth/ accessed 11 February 2024.

- ^ Jonathan Jones, “Where the internet lives: the artist who snooped on Google’s data farm The Guardian,” 4 February 2015.