All that saying says

Same as laying about

– Lionel Fogarty[1]

The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?

– Fred Moten[2]

Sil: Just when I thought I was out… They pull me back in

– The Sopranos, (from The Godfather Part III, 1990)

So I had the idea of giving the issue no title. As in not ‘untitled’—just actually nothing. No title at all. To me it plays a double game—one, it realises an unspeakability; and two, it would highlight the awkwardness of the labelling of Artlink Indigenous, which will obviously indicate ‘the brand’ on the cover somewhere. Because really, why does it need to exist like that at all?

Indigenous art is mainstream. This phenomenon is not new. Those who’ve studied or been part of its history will say, will know, this has been a decades-long process. Our works are collected in every major institution in the country, shown at international biennales and triennials, written about in arts publications with merit, discussed in conferences worldwide. It perforates most issues of Artlink, as it should. The best Indigenous art is among the most inventive, rigorous, and aesthetically adroit work in this country and across the globe.

For thirteen years Artlink Indigenous has been a platform for Indigenous artists, writers and curators to shape the discourse on Indigenous art and unsettle the settler grammar that structures how we discuss our work. And the Indigenous artists, writers and curators who participated in these issues have paved the way. But Indigenous art must not be understood in its relational and historical context alone: it does not sit outside of contemporary art and a separational approach to talking about Indigenous art—or talking about it but only glossing the surface with anodyne praise or an exoticist awe, which leaves much unsaid—reinscribes a false notion and perception of how our art functions with regard to the rest of the art world. The work of those who’ve contributed to Artlink Indigenous is just as valid as work in any business as usual issue of any publication.

For Dean Cross and I as guest editors, Artlink Indigenous is a chance to say what is unspeakable about Indigenous art and the contemporary art world, discussing what’s obscured by the prevailing axioms, the market drives, the institutional and governing bureaucratic and national anxieties.

On the inside of the art world, in polite company, how can we speak openly and honestly about Indigenous art, the machinations of the industry, while using the (media) technologies of settler-colonialism to do so—the spectator, the critic, is already always implicated. We wanted the issue to be a platform for taking risks—a way Indigenous artists, writers and our accomplices could be in but not of the industry, or put another way, using the platform without buying into its value system.[3]

So, if it is the institutional co-option and commercialisation of Indigenous art that we seek to combat, we work towards the production of anti-value excrement, which is always an excess of the settler-colonial enclosure of contemporary art. We gotta take Indigenous aesthetics walkabout, outside of and from within the art world. In his conversation with Robert Andrew, in which they discuss Andrew’s textual interventions in time/temporal interventions in language, Dean Cross speaks of taking pictures and stories wandering, his visual essay perforates the typical flow of the magazine. The kind of storytelling he describes is a method which also informs this issue:

It’s a choreography. It’s exactly how I would think when I used to make dance. It’s that light and shade; rhythms that provide atmosphere, a sense of something. It makes me think too of old time, pre-contact perceptions of time. You can still see it now whenever you get an elder talking, suddenly the stories are endless. This worded wandering. I think you get a sense of this a lot in subtle ways in work that’s made by First Nations people; a very different sense of storytelling time.

What happens when you go for a walk, have a yarn, round the back or round the side of the gallery, the museum, the school? If you’ve been around or worked anywhere in the art industry, you’ve heard or seen things that are only spoken of with hushed voices in confidence. They rarely make their way into the written word. With our invitation to writers in this issue, we encouraged them to talk about things like the non-disclosure agreements artists sign regarding the artist fees paid by major institutions (rates often felt to be unfair). Or the unhappiness mob have with the way curators sometimes show and write about their work; the relatively high support some remote Aboriginal art centres receive, and the lack of support others contend with, all underpinned by historical amnesia and the disregard for local art histories and their global influence: the editorial brief had no boundaries.

This was a lot to ask of artists and writers, who have their work and lives invested in the art world, as we both do. We’re already stretched thin. Sometimes we make strategic concessions, at other times we’re fucked over, overburdened with ‘opportunities,’ like the bullshit ‘Indigenous identified’ positions that offer inadequate training and stressful, culturally unsafe workloads, or the chance to be in the show, the magazine, if just we’ll play the role: the angry antagonist who provides the counter-hegemonic commentary or one who performs cultural calisthenics. In under-resourced projects, professional development, mentoring and collaboration can be a challenge.

‘Failure goes hand in hand with capitalism’ but in this system success is equated with profit and failure with the inability to accumulate wealth. Success is the story you’ve already heard, the artist you already know, the work that has already shown. Failure is the hidden history of pessimism in a culture of optimism (built on and sustaining the accumulation of wealth).[4]

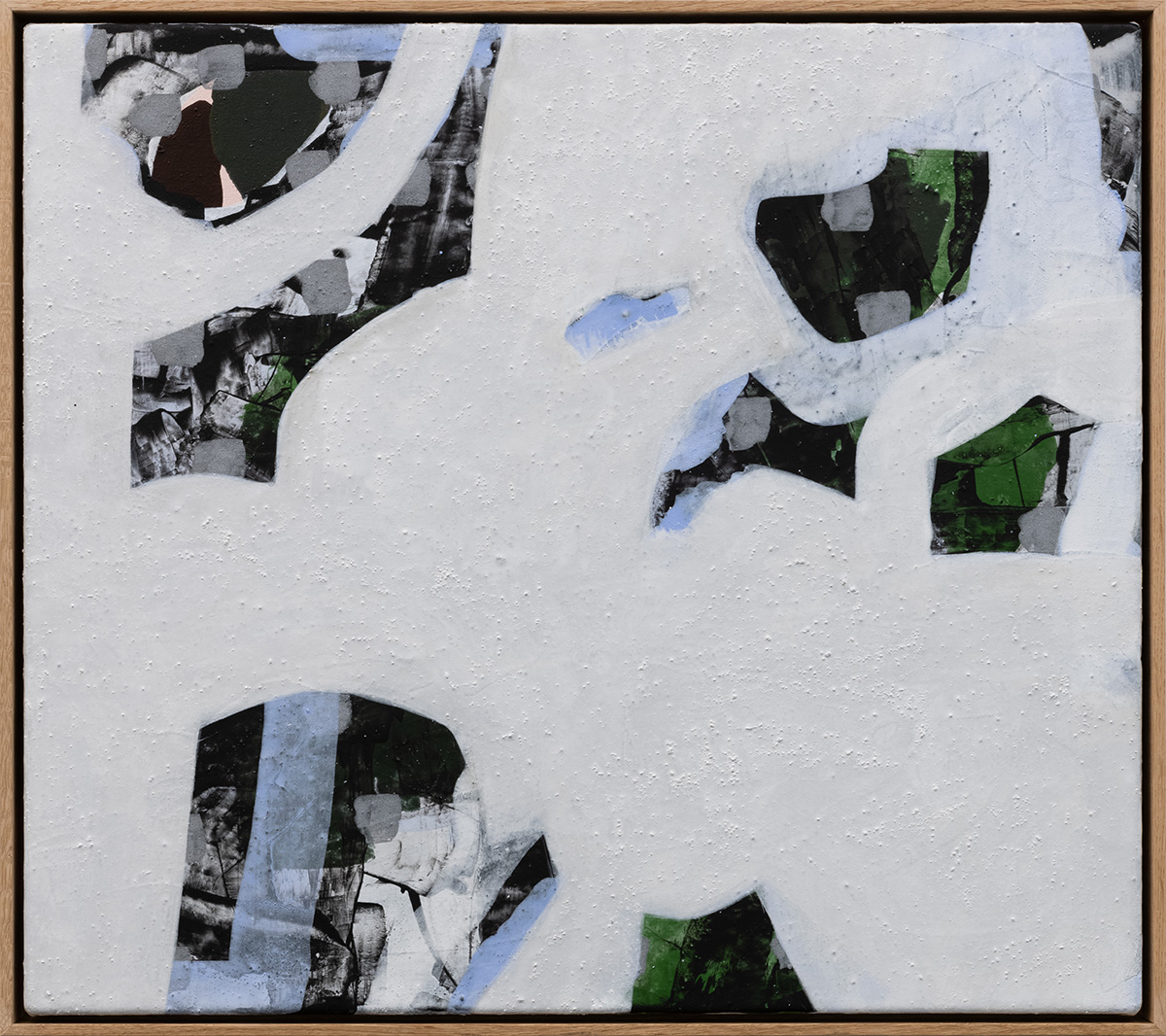

In this risk averse environment, failure is necessary to bring the technologies of settler-supremacy to a halt—if only momentarily. It was inevitable that this ‘unspeakable’ issue would fail in some ways. We had fuck-all time, going wandering doesn’t coincide with hard publishing deadlines. In some cases, texts from authors never arrived. I’ve been in that situation as a writer, other things come up and take priority—as they should. This meant more work for me, at the same time it gave me space to find and generate content, working with artists rather than asking them to deliver. One such example are the pages of Karen Mills’ beautiful paintings, which she calls ‘abstract landscapes painted from memory.’ This piece is not-quite-profile, not-quite-artist pages, but my own reflections on my admiration for a friend’s paintings. Mills’ work is defined by such subtlety and attention to small detail things and ‘the space between things’ as she says. Never didactic or corrective, Mills attends to the break, the space of dispossession, which so many of us mob live with; she complicates the bonds between possession and dispossession.

We had to embrace failure, but it didn’t fail us. After committing to the guest editor role, and in order to tease out our ideas, we approached each author, discussing their contribution, listening to their positions, their arguments and desires. Rather than attempting to shape texts to fit the theme, we worked to sustain and reinforce the writers’ voices. Una Rey assisted with this, her support was particularly helpful when I was exhausted from my other work, my health, and family business. Our editorial assistant Elijah Money gained valuable experience of the publishing process and was great to work with—but we would all have liked more time. Unfortunately, we are all slaves to the gig economy. In this issue we find out ‘what kind of rewards can failure offer us.’[5]

Indigenous art does not exist in a vacuum closed-off from non-Indigenous collaboration, such as an ‘Indigenous issue’ might suggest. All Indigenous art that circulates is already entwined in global and transcultural exchanges. When commissioning writers for this issue, we were open to people of any life experiences, while reserving space for writers and artists who have been systematically cut-out of the dominant circuits of communication. Here we have worked with writers from across the country and the sea, across age groups, experience, and different measures of expertise and knowledge.

Micaela Sahhar in her text, From Palestine to Country: transcultural exchange beyond the settler-colony takes the conversation where it needs to go, reflecting on collaboration between Indigenous and Palestinian peoples. She begins in 1967, tenderly tracing her family’s migration experience, to her experience grounded in this country where, as she says to be Palestinian was to have ‘our identity treated as a dangerous provocation.’ This resonates with me, and I imagine many other colonised peoples. And I think the role the media plays in such villainising—as Sahhar articulates by way of Wiradjuri writer and academic Jeanine Leane—we have voices. What we need is a platform.

Elsewhere, Christine Han takes us to familiar territory in new contexts, in her review of Ever Present: First Peoples Art of Australia, at the National Gallery Singapore. Her reflections on nationalism and her responses to the artworks are paired with observations of the gallery’s imposing, often overwhelming colonial architecture—an all too familiar feeling.

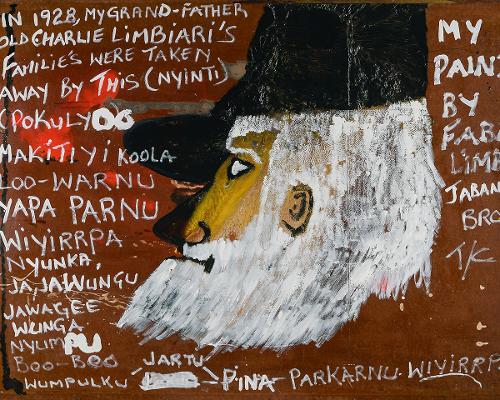

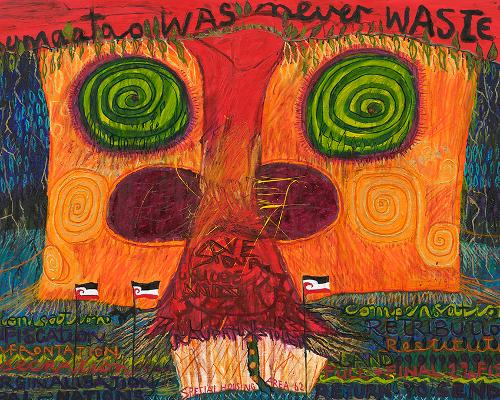

From Aotearoa, Hana Pera Aoake makes a substantial contribution to the scholarship on the work of senior Māori artist and activist Emily Karaka, who for over five decades has been practicing art that provides counternarratives and exposes the trauma that Māori have lived through. Touching on how ‘Treaty’ can be commandeered as a settler-colonial technology of coercion,[6] Aoake writes that Karaka’s work ‘reveals what the Treaty breaches made possible, the taking of land, its development, and the impoverishment and alienation of Māori from that land.’

In the APY Lands of South Australia, Ninuku art centre manager Eila Vinwynn takes us through the minutiae of day-to-day life of working with mob in a remote art centre. She reflects on the role non-Indigenous interlocutors have in the framing and reception of Indigenous art, citing Kim Mahood’s ‘Kartiya are like Toyotas,’ but as we’ve seen in the work of Karen Rogers, the Toyota Troopy is a real player in the making and transport of art out on Country.

In my conversation with mob from Ngukurr Arts, Rogers’ Troopy paintings are just one of the topics we wander through. The Ngukurr artists’ ground-breaking output since the art centre’s conception decades ago has been without a coherent style—in a productive way. What binds the work of Ngukurr artists is, as Rogers says in our talk, the use of bright colour. Ngukurr Arts is unique in this way, where artists’ intellectual inquiry and aesthetic experimentation takes precedence over traditional rules and commercial, art world conventions. Although the support that Ngukurr Arts receives is negligible compared to the brand name art centres, its artists are at the forefront of re-redefining Indigenous artistic practice.

Following Ngukurr’s lead, discord is intentional through this issue. A soundtrack to my editorial style goes randomly from anarcho-punk band Conflict’s The Ungovernable Force (1986) to DJ Screw’s My Mind Went Blank (1995) and Horace Andy’s ‘80s anthem, Stop The Fuss. Country/folk singer Karen Dalton’s version of Reason to Believe (1966) and the beautiful, haunting Garmal by Kevin Jawungurr and Leon Badicha recorded on the ‘Maningrida Regional Partnership Compilation’ (2006) resonate too. I don’t aspire to harmony, and I don’t want to reduce anyone else’s art or writing to a theme.

The Cure plays diegetically in the background as Tamsen Hopkinson sits down with Archie Moore in his home in Ngudooroo (Lamb Island) in Queensland. Together they discuss his large-scale architectural installation Dwelling (Victorian Issue) (2022), recently seen in its fourth iteration at Gertrude Contemporary in Narrm. Covering spatial and temporal ground, they talk about intergenerational memory, racism, TV and music. As Moore says, ‘objects have an aura about them and people have their own memories and emotional attachment to them, especially trinkets.’

The Tennant Creek Brio make use of the excesses of extractive capitalism, working with the excrement of the mining industry. With insights drawn from working with ‘the Brio’, Lévi McLean and Paris Lettau run us through the rapidly expanding appetite for and literature on the Tennant Creek mob’s art practices. I’m reminded of Djon Mundine opening the Brio’s Shock & Ore (August 2022) at Coconut Studios in Darwin: breaking from his speech, he rapped 50 Cent’s Many Men (Wish Death) and Don’t Push Me (2003) in a wildly apt and iconic introduction to the exhibition. (We anticipate similar departures in his Artlink archive essay aligned with this issue). McLean and Lettau similarly go off script in their urgent text on one of the country’s most dynamic artistic collectives with a poem: Mangkururi (2022) by Brio artist Joseph Williams Jungarrayi:

Mangkajarri apparr jangu

Ngurramala jja pinanta

kapi nyanjjan

Kumpumpu kana kunurla

Angi nyinkurn wini ku purtu

Winanta anyul pulkka pulkka jja

Malarra malarra jja(Mangkajarri will tell

you the story

Unknowable spirits listen

Keep it in your mind

Or be without name

A reason to sing

Young and old)

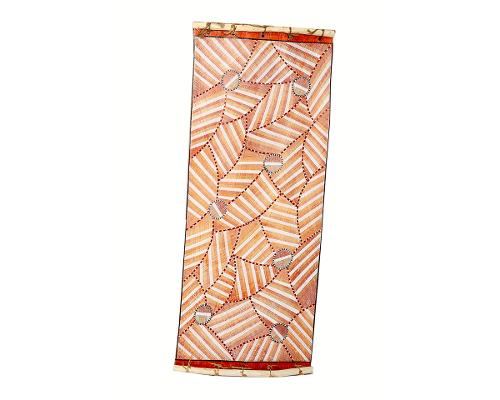

The space between translation is not simply one of loss, but of loss and generativity. Regardless, when artists are able to speak in their first language, they stay symbolically closer to their work. Kenan Namunjdja speaks in his language, Kuninjku, about the Ancestral motifs that he paints in ochre on bark. ‘O yiman kunkurra njalehnjale manekke kunkare rerri ngahmarnbom yiman nungkah marnbohmarnbom. (Or like the wind dreaming or other subjects, I do the same ones as my father used to make)’, Namunjdja tells us of his practice, which is deeply informed by kinship and spirituality.

Multilingual artist Curtis Taylor, with his sculpture Justice (2022)—our cover image—and his writing on some of his recent works and exhibitions in Boorloo / Perth resolutely shows that even within the increasingly limited encampment of the mainstream art world, artists can find ways to disrupt convention. Taylor’s work cuts across all expectations and cultural essentialisms, grasping with language, material, aesthetics and blood. He concludes his text with a sentiment that I share and which I believe vital to Indigenous art and artistic practice in general: ‘being brave, bold on the cusp of safe is what we should all experience: if there is no freedom of expression then beauty of life is lost.’

Footnotes

- ^ Lionel Fogarty, “What Saying Says,” Minyung Woolah Binnung: What Saying Says (Southport: Keeaira Press 2004), 63

- ^ Fred Moten in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions 2013), 10

- ^ Moten

- ^ Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press 2011), 88

- ^ Halberstam, 88

- ^ la Paperson, A Third University is Possible (Minnesota: Forerunners: Ideas First 2017)