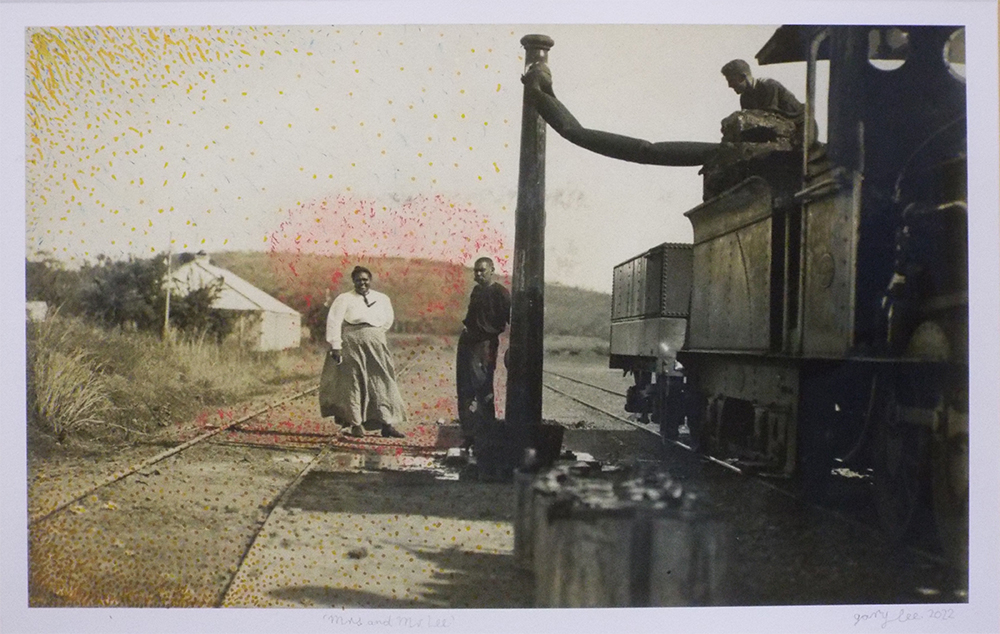

Courtesy and © Gary Lee

I want to say it’s warmer now. I’m back down south; it nears two months since I visited midling, a small exhibition of photography and illustration by the luminary artist Gary Lee (Larrakia) at Coconut Studios in Darwin. The memory of midling glimmers like the morning sun through gaps in the curtains of time. I draw the curtains back fully now, recall the fragile serenity of images that trace the ineffable beauty between things.

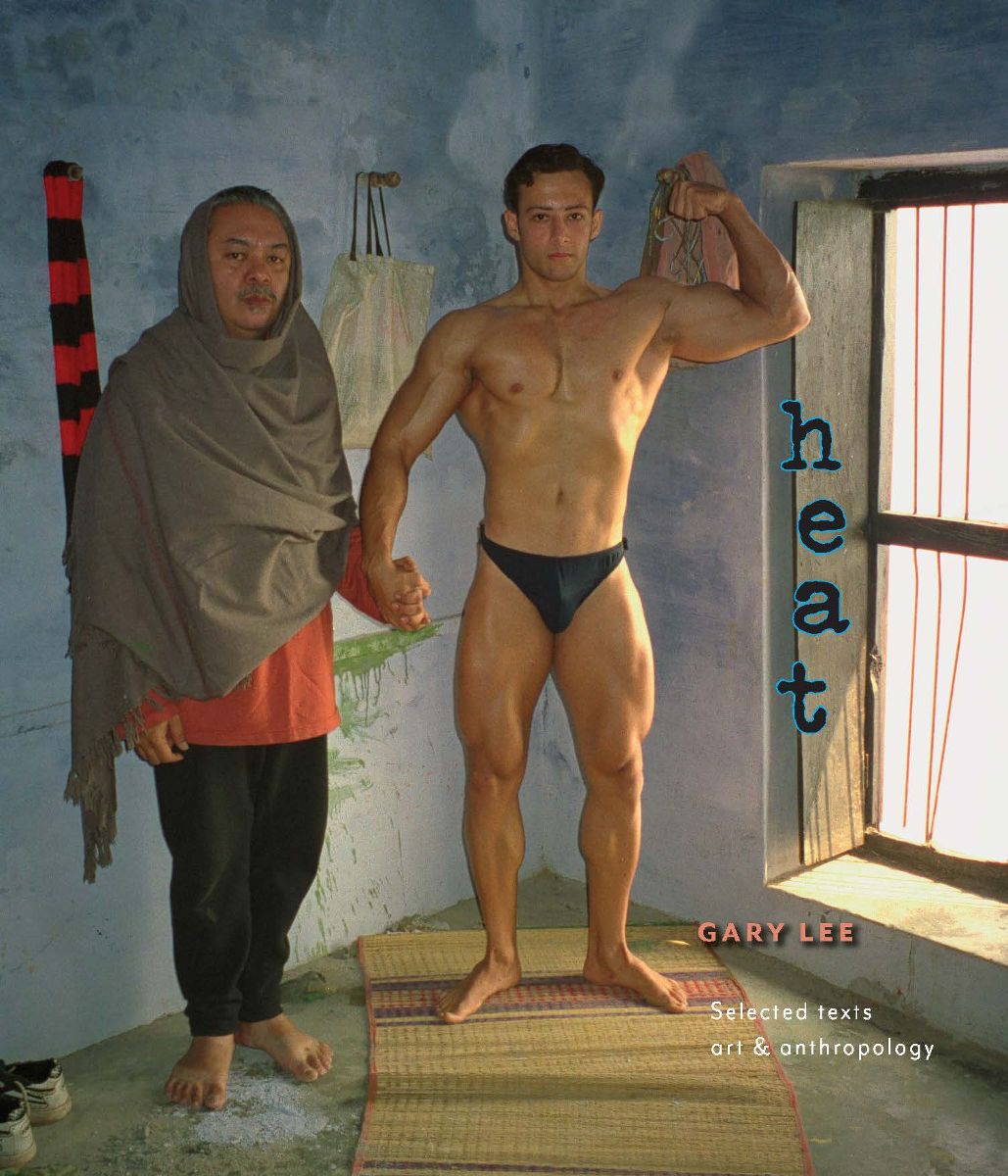

In spite of distance (two months, 3,000km, slow effusion of spring, taper of memory by night, beautiful questions that disappear), lemme recount now: midling consists of fourteen new and remade works that delve into photographic archives (personal, family, and historic). The exhibition was also a stage to launch Heat: Gary Lee, selected texts, art & anthropology (2023). The anthology edited by Maurice O’Riordan—who also curated the exhibition—spans five decades of Lee’s writing on art, his own and others, and Larrakia and Indigenous culture. If midling is a demure reflection on Lee’s artistic career so far, Heat turns it up, lets it hang out (as it should)—divulging all facets of the artist’s practice and simultaneously documenting the expanse of Indigenous arts practice.

Heat is a perfect title for a book on Lee’s career as artist, curator, writer, and anthropologist. There is the heat of Darwin, Lee’s hometown, and heat as metaphor for the desire in Lee’s photographs of semi-nude and nude bodies. Across the pages, heat acts as a kind of metonym for the moral policing the artist has encountered. Lee has copped heat from the kind of motherfuckers who in the private brutality of their delicate sensibilities don’t want to see what Lee sees as the beautiful faces, arms, abdomens, cocks and legs of the people he photographs.

In one instance at the 2006 Dreaming Festival in Woodford on the Sunshine Coast, Lee’s series Nice Coloured Boys (1994–), a homoerotic study of elastic masculinity, was censored by the festival staff. In Heat, in conversation with the eminent artist Tracey Moffatt, Lee recounts having to take down his exhibition because of pressure from festival staff.

Contrary to this kind of anecdote, the Lee of Heat isn’t an artist who courts controversy, rather he constantly works toward complexity in expression, seeking an eloquent articulation of qualities that are beautiful but have often been cast as otherwise. Lee is perennially the artist of otherwise. Reading Heat, the history of Indigenous art is a queer and trans history in that Indigenous art is always elusive to—and in excess of—any normative definition. The way Jack Halberstam puts it in Trans* is that typological naming, or ‘the mania for godlike naming began, unsurprisingly, with colonial exploration.’[1] The otherwise is that which never collapses under any such name.

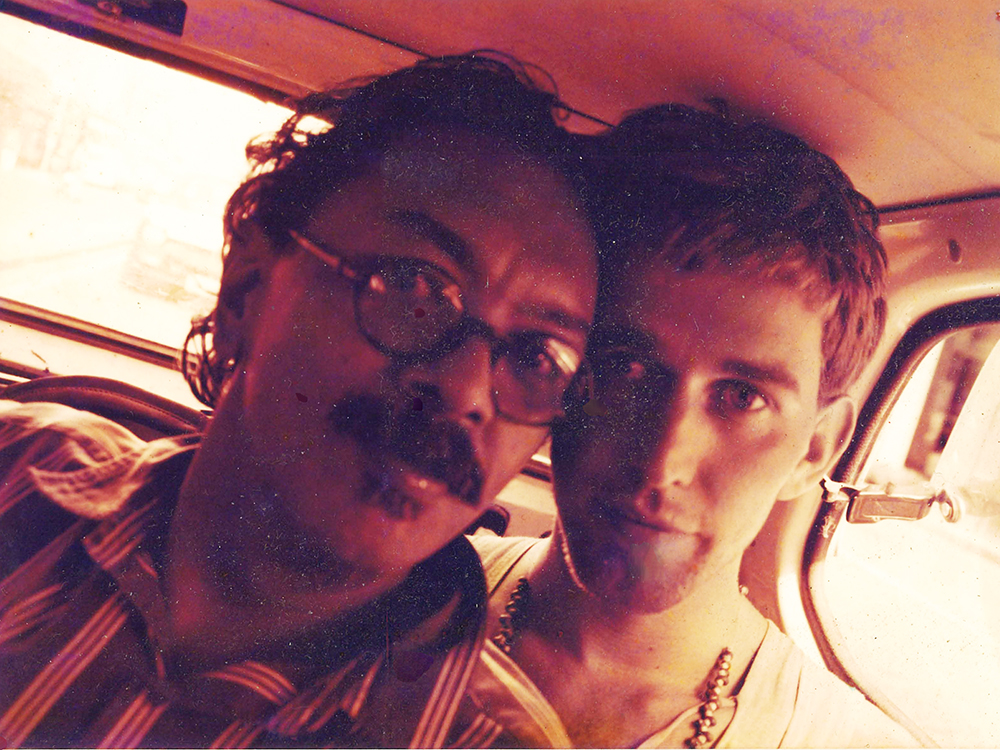

In the middle of Heat, the article ‘Love doesn’t have a colour’ concurrently chronicles the love story between Lee and O’Riordan, doubling as a critical engagement with the interplay between racism and homophobia as experienced by an Aboriginal and an Irish-Australian gay male couple. Here, text and image are inextricable. The tone of the text is set by a photograph of Lee and O’Riordan taken in the backseat of a car in 1991 in the vein of Wong Kar-wai’s 1997 film, Happy Together. Taken six years before the film’s release, the photo, (although not taken by Lee), demonstrates how the artist is in dialogue with—and has sometimes pre-empted—traditions of queer image-making.

Heat sways the understanding of Indigenous art history. Like midling, it is grounded in a Larrakia lifeway, in what is known inter alia as Darwin. What’s different is that the book as an object can go walkabout and is here with me now in an apartment on Wurundjeri Country. I’ve got it on the table sitting with Fred Moten’s Perennial Fashion Presence Falling (2023) and it’s like the two of ‘em really been talking, when Moten writes ‘can that we survive destroy what we survive…?’ and Lee responds: ‘art […] begins with the recognition of irreparable loss.’

Lee writes this in ‘Dirula: Contemporary Larrakia Art,’ when he’s talking ‘bout how Contemporary Larrakia Art came about: ‘the establishment of Darwin (formerly Palmerston) on Larrakia lands from 1869 meant that Larrakia people bore the full brunt of colonisation in the Top End, manifest through widespread dispossession, genocide and introduced diseases…’ It’s not simply that these fucked-up, life-devastating things happened, it’s that Larrakia mob found a way to make something after the end of the world. Lee’s work is a testament to how art is a poetic vision that cannot remake what is lost, but makes again and again something new, something otherwise, out of the shared knowledge-experience of such loss.

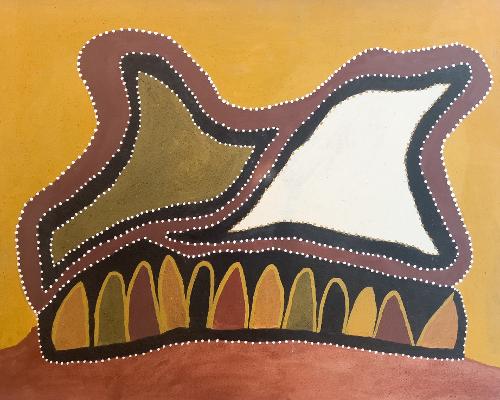

This is what happens. A few pages later, you come to realise now that ‘Dirula: Contemporary Larrakia Art’ is a catalogue text for the 2002 exhibition of the same title, which Lee curated at 24HR Art | NT Centre for Contemporary Art. Turning over the fourteen pages that document the exhibition in text and image, reveals that Dirula is probably one of the most significant exhibitions ever dedicated to Larrakia art. The exhibition brings together work by Lee and his brothers Gullawan Roque and Anthony Duwun Lee, Prince of Wales and Topsy Secretary, among others.

opening, 24HR Art, Darwin, 2002. Photo: Maurice O’Riordan

Heat makes connections: there is the text and images of the art in Dirula, but also the opening night photos with Lee and Brenda L. Croft, Hetti Perkins with baby Otis, and Judy Watson’s mum Joyce. So all them Larrakia come together in that show and mob come from all over to have a ‘big eye’ (as Lee states in Heat ‘big eye’ is a Larrakia/Aboriginal English term with wide application ‘from a curiosity and fascination to an interest in the beauty of someone or something’).

Togetherness—what might also be referred to as relation in the terms of French-Martinique philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant—is a theme that flows through midling and Heat.

Midling is a Larrakia word meaning together and Lee imagines togetherness as he shapes it. This imaging-shaping is psychic and physical. In light of Lee’s intimate photos—often focussing on a single subject, a nude or shirtless young man, photographed in a point and shoot style as if to suggest a desire for minimal technological interference between the photographer and his subject—midling might reveal how the artist thinks of photography or the photograph as a kind of transliteration of togetherness, which is always provisional insofar as it always suggests and evades oneness.

Togetherness isn’t simply a unification or the side-by-side arrangement of two seemingly discrete entities/bodies, but everything unnamed or yet to be named that happens between the two. It’s like this, I think: the collapse of distance is not only spatial as with Stefan (2009) from Lee’s On the Verge photographic series, it is also temporal as in Mei Kim and Minnie (2006).

Up the back of the Darwin gallery, Stefan is stuck to the wall without a frame, making the figure in the photo and the photo itself semi-nude. Here is a small photograph of a shirtless boy posing among glossy green foliage, his brown eyes softly meet our gaze, he looks to be within reach of the photographer, and the point-and-shoot framing suggests immediacy and a collapse of distance—due to the camera’s range (or lack thereof)—here it is first the artist and subject who are together spatiotemporally, in this moment and second, the viewer in a re-iteration that perpetually alters the nature of togetherness.

In Mei Kim and Minnie (2006), one of Lee’s few photos that isn’t concerned with homosociality and variance in masculinity, two portraits of Lee’s female relatives are placed side-by-side. In this diptych, each of the women is topless, Mei Kim, shot by Lee in 2006 is adorned with a tattoo on her right breast, a name in cursive that I can’t quite read. Minnie on the other hand was shot in 1887 by colonial photographer, Paul Foelsche, in an ethnographic style. There is a quiet, ancestral dialogue between Minnie and Mei Kim on a kind of spiritual level, the tattoo and (Minnie’s) scars tell us as much as they conceal; about the relation between the two, about how we conceptualise age and maturity, kin and intergenerational transference and how bodies remember.

Here there is a collapse of historical time, in the catalogue essay O’Riordan refers to it as ‘ancestral togetherness.’ This togetherness is a recoding, always necessarily unfinished, of the bio-facticity of Indigeneity, which is construed but never fully captured in the ethnographer’s photograph. Heat responds to Moten’s beautiful question of ‘can that we survive destroy what we survive…?’ With art, we utter ‘yes’ again and again.

This is how we got here. Heat is an undeniably significant contribution to Indigenous art history and vital for anyone in any way serious about Indigenous art today. Get to it.

Footnotes

- ^ Jack Halberstam, Trans* A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 3.