Search

You searched for articles ...

I saw the sun

I sang my song

I danced my dance

I saw my shadow

I saw my soul

I made my mark!

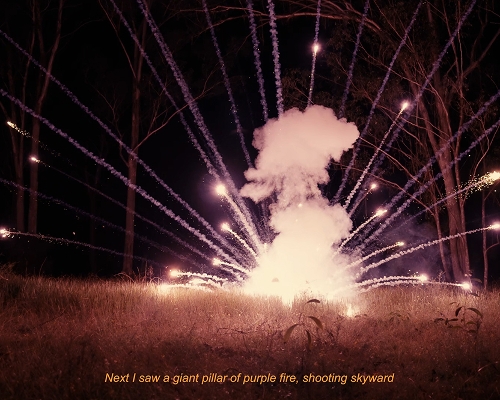

Historically, Aboriginal people across the continent, whether intentional or casual, could identify the presence of another named person from their indexical mark; footprint, handprint, bum print or body print. It was the first art, and marked this site as my land. This idea was behind my performance I saw the Sun, in 2004, under the Story Bridge in Brisbane, in which I stripped down and danced as the rising sun left my mark as a shadow (the ancestral spirit) on the river’s muddy shore. Made into a video, it was included in two exhibitions in Brisbane in 2004 and 2005.

_card.jpg)

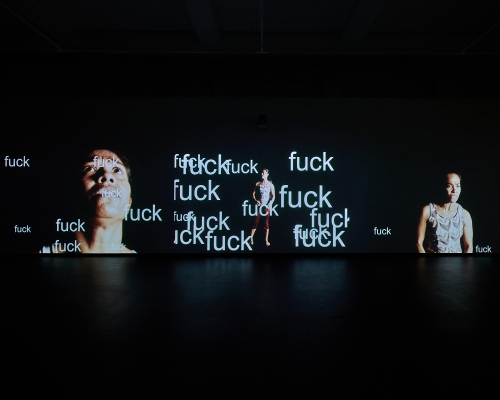

This article featuring selected paintings by the multimedia artist Khaled Sabsabi was commissioned and drafted well-prior to the furore surrounding his celebrated appointment (with curator Michael Dagostino) to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale. The appointment was rescinded only six days later. As an art historian undertaking the unruly task of writing about contemporary art as a type of future history, I feel compelled to contextualise my original article, which I proposed as a reflection on Sabsabi’s more contemplative material practice.

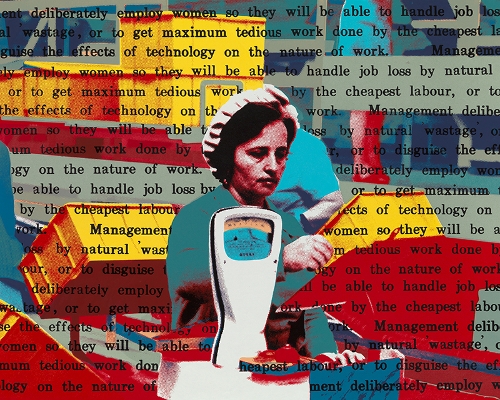

The last essay I contributed to Artlink examined recent curatorial efforts to insert Philippa Cullen (1950–1975) into the canon of Australian feminist performance art history. The revisionist energies amplifying the contributions of an emerging experimental artist of the early seventies, were institutionally performed via the National Gallery of Australia’s (NGA) Know My Name project. As important as the project has been in critically redressing gender imbalance and historical gaps in the NGA’s collection, it stirred great debate and highlighted the multitude of important female-identifying and non-binary artists, living and dead, who fail to cut through.

In August 2024 I joined Wollongong Art Gallery as its seventh director in its almost 50-year history. Immediately immersed in its large collection as a crash course in its cultural and sociopolitical contribution to Australian (largely regional) art history, I kept returning to the enigmatic work of a local and long-forgotten painter Joan Meats (1920–2003).

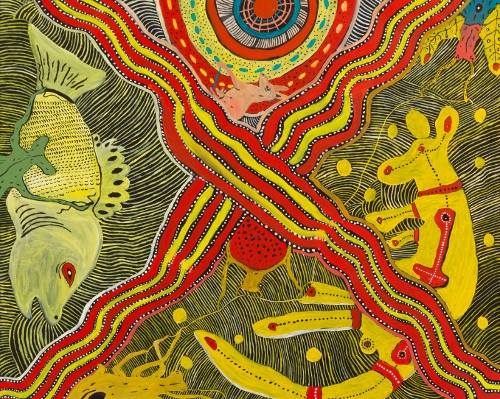

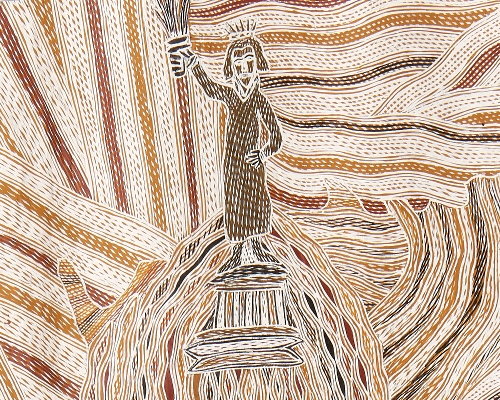

April 2025 marks twenty-five years since Rusty Peters (Dirrji) and Peter Adsett painted Two Laws One Big Spirit at Humpty Doo near Darwin. The fourteen canvases—seven pairs, in formal association with each other—are now permanently housed in the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), gifted by GRANTPIRRIE.

A quarter of a century is a long time in the politics of reconciliation, the framework within which the series has mostly been discussed. ‘A dialogue in paint’ as Adsett refers to the career-defining project, the works are evidence of a correspondence between unlikely painting peers, born of acutely different world views and visual vocabularies.

A lover whilst exiting my life, turned to say “l never really loved you. l loved your art.” It wasn’t the biggest burn. I consider myself the art anyway. It’s the best part of me. Really, actually, the only me. There is so little of me (‘my’ life). I have extra territory to make a variety of art personas.

- Diena Georgetti, in conversation with Melissa Loughlan 2025

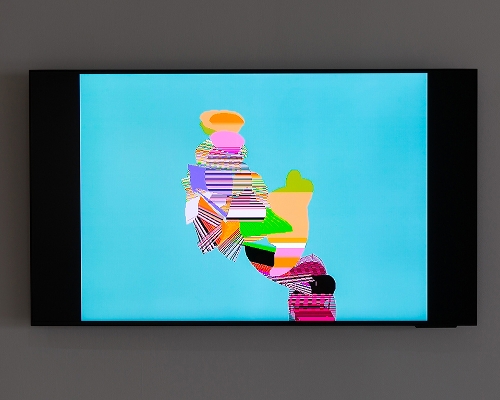

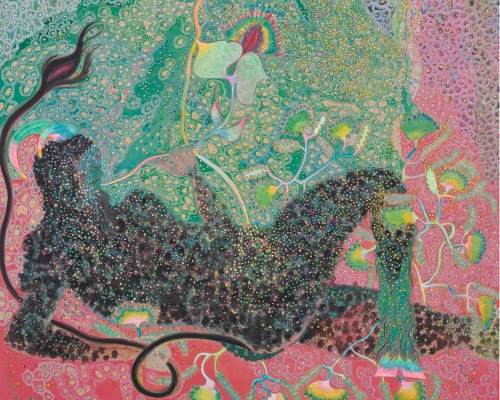

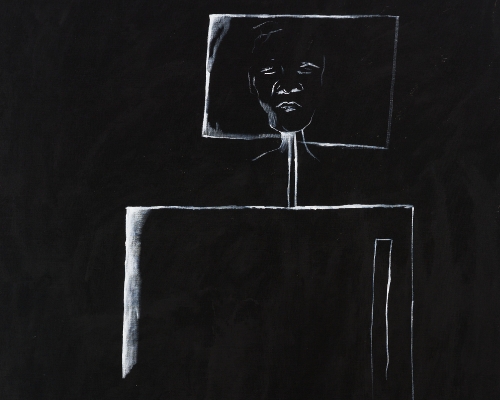

Diena Georgetti’s recent paintings eschew anecdotal narrative, but nevertheless conjure a labyrinthine backstory that interweaves a complex stratum of influence, personal necessity and artistic identity. It would be more than glancingly accurate to see these works both as insights into the dichotomy between creative impulse and control, and as vehicles to some place of release or repose.

Organic matter turns into compost when it breaks down.

After brewing my cup of tea, I place wet tea leaves into my kitchen’s compost bin along with other food scraps, which I later add to my garden’s compost.

Compost over compost.

Time over time.

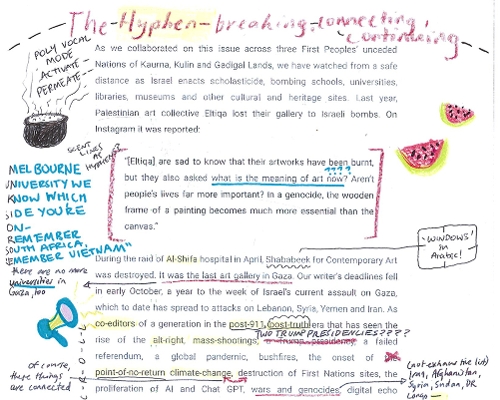

I write these words at exactly one year of ongoing brutality and genocide in Gaza, during the 76th year of Zionist occupation of Palestine.

I can’t help but think of what else belongs in a compost bin.

Zionism.

Militarism.

Capitalism.

Colonialism.

Extractivism.

Expansionism.

What other words that end with ‘ism’?

Which outdated world views, ideologies, systems and structures belong in a compost bin? What skeletons and bones need to break down to birth something new?

Queensland is the most decentralised state in mainland Australia, with more than half of its population living outside its capital. Gimuy/Cairns, a city of approximately 150,000 people, is closer to Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea than it is to Brisbane. A gateway to the Great Barrier Reef and the World Heritage Listed Wet Tropics rainforest, Gimuy/Cairns is a both a tourist destination and a regional centre, in addition to serving as a vital services hub for communities on Cape York and the Torres Strait Islands.

For a city of its size, Gimuy/ Cairns has a healthy number of exhibition spaces, including the venerable Cairns Art Gallery, the Tanks Art Centre and Court House Gallery, the latter both operated by the Regional Council. There is also NorthSite Contemporary Arts, a gallery, retail and studio- based organisation founded by local artists as Kick Arts in 1993, the year that Queensland Art Gallery (now QAGOMA) launched the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, putting the institution, and the state’s nascent contemporary art scene, on the global map. Like many centres, Gimuy/ Cairns lacks sufficient studio space, with the exception of the former Djumbunji Press, a purpose-built print studio in Edge Hill, which NorthSite has recently taken a long term lease on with plans to reenergise the region’s once dominant printmaking scene.

North of the Capertee Valley, on Dabee Country, is Combamolang, a long mountain with multiple peaks and outcrops. The mountain’s slopes form a dramatic escarpment above the flat land below where the silos of a factory stand out amid the bushland. Beside the factory is Kandos, the town built for the cement workers when the industry was established here in the early 20th century. It has a wide main street with civic buildings and shops under awnings, extending out into a grid of residential streets that end at the foothills of the mountain.

Since Kandos was established in 1914 it has developed its own distinct identity, drawing people to it first for its industry and, more recently, as a centre for regional arts. Following the closure of the cement works in 2011, the town has become a locus for place- based, socially engaged art practice. In the early 2010s Cementa festival founders—Ann Finnegan, Georgina Pollard and Alex Wisser—moved to Kandos, bringing their experience as arts workers and their enthusiasm for sustaining a contemporary art community. The first Cementa occurred in 2013, and the upcoming Cementa24 is the sixth time the festival has run, this time guest- curated by Daniel Mudie Cunningham and First Nations curator Jo Albany. It marks a new phase—with the festival coming into its second decade—with an established presence in the region and on the Australian arts calendar.

In December 2022, four staff at the Broken Hill City Art Gallery (BHCAG) and Museum resigned after a year- long public debate over art, local identity and heritage in one of Australia’s most iconic ‘outback’ towns.

I moved to Broken Hill in January 2021 to take up the role of Programs Officer, later employed as the Curator, at the Gallery. I often describe moving to Wilyakali Country as humbling. Having spent most of my life in the inner suburbs of Naarm/Melbourne, I quickly learnt that nothing is theoretical in a small community. Relationality is essential. In my first month, I was stopped by a local and asked if I was an ‘A-grader’. I would come to understand the subtext of this question, perhaps more of an accusation than genuine inquiry. A mining boom turn of phrase, if you were born and bred in Broken Hill, you were considered an A-grader; if you married in or lived in Broken Hill for many years, a B-grader; anyone else was a C-grader. Today, this persists with the more palatable notion of being ‘local’ or what’s known in Broken Hill as ‘from away’ (that could be Dublin, Dubbo, New York or simply the next town over).

I grew up in the regions. I still refer to myself as a country kid. I grew up close to Country on the Wotjobaluk- tended lands of Horsham, over three hours’ drive northwest of Melbourne. My ancestral homelands were slightly further north: the fresh-and-salt- water lakes known by my Wergaia and Wemba-Wemba ancestors.

In Horsham, our family felt like an anomaly. My Aboriginal father had died when we were young, my English mother remained in Australia to raise us, and she was an artist involved in the rich cultural life of our town. For me, and many others, the creative heart of regional communities was both life giving and life-saving.

Tough luck to the wood that becomes a violin.

– Arthur Rimbaud, letter to Paul Demeny, 15 May 1871

The picture which is looked to for an interpretation of nature is invaluable, but the picture which is taken as a substitute for nature, had better be burned…

– John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1844

Like an enveloping atmosphere, ecology has become a dominant framework for contemporary art. In parallel, criticism has assumed the task of interpreting and re-interpreting art and its history for the ecological moment. Despite its near-imperialistic tendency to redefine the meaning of art works in ecological terms, the use of ‘ecology’ as a framework often precludes critical analysis rather than invites it. We are compelled to equate ‘ecological’ alongside terms like ‘life’ and ‘care’, with ‘good’, neatly bypassing both aesthetic and political judgment. Ecology is levelled to any lively, activated network, ignoring the dead, inorganic and artificial aspects of real ecologies. In the efflorescence of eco-art, the living overtakes the dead at the cost of art’s function...

To continue reading...

Lucienne Rickard’s Extinction Studies (2019–2023) was a long durational, live drawing project commissioned by Detached Cultural Organisation and staged in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery’s Link Foyer spanning four years and three months. Delivered in two iterations, the project focused on extinction as a key concern of the global ecological crisis and a phenomenon much talked about, but rarely witnessed at close range. Informed by links between the destructive impact of human activity within the Anthropocene and the ‘sixth’ mass extinction event, Rickard’s daily presence in the Museum framed extinction as a phenomenon to which we might bear witness in the here-and-now. Employing the double-edged strategy of drawing an extinct or endangered animal on a large sheet of paper and then erasing the image, Rickard’s project alluded to evolutionary cycles as viewers could witness, sometimes over months, the emergence of an anatomically accurate creature, only to watch it disappear in minutes under her eraser.

To continue reading...

It’s 2am, and I am editing images on my MacBook Pro to include in this visual essay. I am using the Pomodoro method while I work, my iPhone keeping track of time. I am thinking about rare earth elements (or REEs, or rare earths) and their wide use in contemporary art, particularly media art, photography, video, film and animation. If life cannot be separated from art, then it is impossible to have an art practice in 2024 that does not depend on the mass-scale extraction of stolen Indigenous land and resources.

To continue reading...

2022 Tiyari, Tiwi season of hot and humid. We felt unsettled watching the news of Jikilaruwu Tiwi Island clan seniors taking South Korean Government to Seoul Central District court; a sip of solidarity beyond state borders to halt financing Santos and SK E&S Barossa Gas Project near Tiwi Islands. But the court dismissed the case after two months as foreign environmental rights are inaccessible to the Korean constitution. In scrutiny, ‘rights to clean air’ as basic rights is categorised under South Korean private law, which was a seeded sacrifice when the constitution was first drafted in the ‘60s after the Korean war—the beginning of economic boom and resource privatisation. This underlying legislative code of proprietary extractions has been reinventing “natural environment”, “resources” and “wealth” using becoming-Global-North colonial science, where the environmental law in Northern Australia is sprouted from these legislated Ponzi schemes.

To continue reading...

I have never seen a Gouldian finch “in the wild”, but over the past two years I have become familiar with its image on signage in Darwin streets and byways along with the words Save Lee Point. This typically shy, mostly silent and endangered bird is the brilliant icon of a grassroots movement to protect one of Darwin’s last remaining woodland corridors.

To continue reading...

Some things won’t change, a woman told me in a small room on Bundjalung Country, filled with other women weaving; the smell of raffia and pillows. It was raining so we couldn’t sit outside. I began to weave a circle.

We thought we trusted the bush to be there, but then fire comes, Ruth said. We thought we could turn to the river, but then it overflows. The places we take refuge don’t feel so safe. But we can count on galaxies and bacteria and stones to be around long after we are gone.

Driving my carbon-belching hatchback from one colonial settlement to another, I listened to a book about microbes under a slivered moon. Fires flanked me at one point on the road. They weren’t close enough to scare, contained, but there: the contents of my gut, and the flames.

To continue reading…

The art-raft project is, in Hakim Bey / Peter Lamborn Wilson’s words, a materialised ‘temporary autonomous zone’, where collaborators and activists have space to playfully propose questions, be involved in a common cause, generate connection and envision more positive future narratives.

The project began as a response to the needs of the People’s Blockade, a peaceful ‘flotilla’ protest organised by Rising Tide, held annually in the harbour and river mouth of the Coquun/ Hunter River, at Muloobinba/Newcastle. United on Awabakal and Worimi land and waters, the November 2023 protest saw 3,000 people occupying the world’s largest coal port for 34 hours.

To continue reading…

South Australian creative duo Laura Wills and Will Cheesman are the artists we need for the future. Partners in life and work, the pair have collaborated informally for nearly two decades, since the mid-2000s. Working across public art, relational and participatory practices, the duo—formalised as Wills Projects in 2020—invite many hands to co-create and deliver their projects, promoting non‑hierarchical structures of engagement that cater to the capacity and diversity of their participants. Based in Tarntanya / Adelaide, on Kaurna Yarta, Wills Projects is an exploration of the artists’ action-oriented yet reflective way of responding to the world. Prior to meeting, the pair lived parallel lives, riding bikes around Australia, living in squats in Europe, volunteering and WWOOFing, all while creating art. These experiences brought them together in what Wills refers to as ‘a shared culture’.

To continue reading...

decolonial poetics (avant gubba) (2017), by Bundjalung poet Evelyn Araluen, captures a poignant facet of Katie West’s practice: ‘there are no metaphors here’ [poet’s spacing]. Amid the turbulent aestheticisation of changing climates, biodiversity, colonial legacies and land management, Araluen cautions us to ‘…not touch the de’ [poet’s emphasis]. The rapid adoption of “eco-critical” and “post”-colonial curation, making, staging and writing, in recent times, manifests in work that leaves us with an ecological feeling, a subtle gesture or zephyr. The process of decolonisation, however, cannot simply linger in the air, resting in the conceptual world. Nor can the “eco‑critical”. There is little room for the metaphorical rendering of these material challenges. The relationship between anticolonial projects and environmental consciousness is pervasive, and the health of Country mirrors the health of peoples. The theft and degradation of land always follows in colonialism’s footsteps: Violence inscribed upon the land is inscribed in both minds and bodies.

To continue reading...

In addition to the well-known effects of climate change—melting ice caps and rising sea levels, the increasing frequency of natural disasters, drought and dangerous heat—there are more subtle, psychological affects: feelings of anxiety or dread while thinking about the future, exhaustion and fatigue when reading news stories about the climate emergency, or a churning stomach when trying to come to terms with our limited agency in the face of this capitalism-induced climate crisis.

To continue reading...

Leading up to the first sculpture exhibition held in the grounds of Hans Heysen’s 132-acre property, The Cedars, in March 2000, the area around the shady pool, the site of one of Heysen’s iconic paintings, had slowly been cleared of the head-high broom that covered much of the estate. The back-breaking working of cutting and swabbing the weeds was undertaken by a group of volunteers headed by environmentalists Trevor Curnow and his partner Helen Lyons as the group Trees Please! (an offshoot of Trees for Life), established in 1998 to support the preservation and regeneration of the remnant bush at The Cedars. The late Helen Lyons was a local Hahndorf artist, and her connection with The Cedars landscape inspired her idea of holding an exhibition of installation-based artworks in the vicinity of the shady pool. She had previously founded The Artist’s Voice collective in 1997 and had artists ready and willing to be involved in the venture. The Artist’s Voice members exhibited regularly at the Hahndorf Academy’s upstairs gallery, but some members were open to Lyons’ vision for a non-commercial, experimental exhibition at The Cedars focused on environmental principles. The Cedars’ long-term curator, Allan Campbell was also supportive, and Lyons invited the twelve participating artists to make works in direct response to the landscape, making use of materials found on the property. This inaugural exhibition, A Homage to Nature was the first of many, now known collectively as the Heysen Sculpture Biennial, a series which can be considered a visceral response to the environmental art movement that emerged globally in the 1960s.

To continue reading...

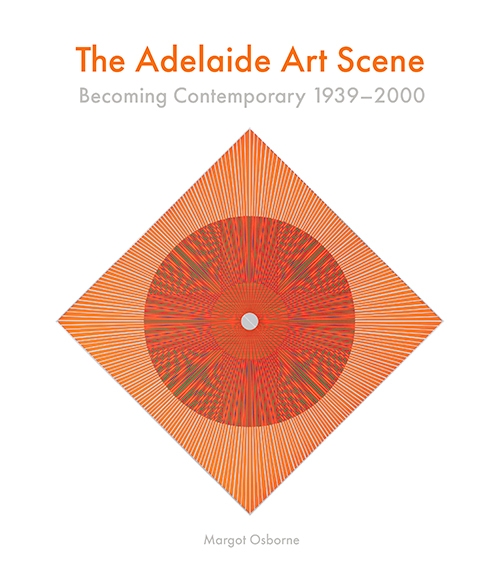

Bernard Smith's assertion in 1943, that it is "truly absurd nowadays to talk of 'modern art' as a single entity," encapsulates a sentiment that has persisted through the decades and finds resonance in Margot Osborne's exploration of Adelaide's art scene. Osborne's work, a solidly researched and expansive history, with re-printed archival material and an extensive index forming a doorstop omnibus which chronicles the critical historical events and figures who have shaped Adelaide and South Australian art.

Through a series of overview chapters by Osborne and commissioned essays by a range of experts and veterans of the local scene, (alongside anecdotes from cultural commentators including poet and publisher Max Harris, critic Robert Hughes and Stephanie Britton, founding Editor of Artlink), Osborne's encyclopedic compilation of essays illuminate what she argues is the uniqueness of Adelaide's artistic landscape between 1939 and 2000, while situating it within broader cultural and socio-political contexts of Australian and international art.

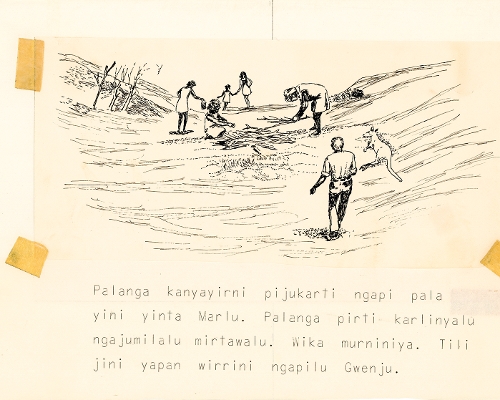

Tjukurpa – handle it. These are the words stencilled above the door into the Wati (Men’s) Studio at Mimili Maku Arts Centre in the remote community of Mimili on the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. One of Robert Fielding’s early geopolitical interventions, these aerosol words mark a threshold into the space where Fielding makes art. Placed high on the lintel, the letters herald the power of the studio and acknowledge past grandmasters, as Fielding calls them, and those to come of the Mimili art movement...

In recent years, Cairns has blossomed as a centre for First Nations artists and curators, many of whom have migrated from Cape York and the Torres Strait Islands. Along with the growing success of the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, there are increasing opportunities to show work from Far North Queensland. Artlink invited members of an emerging curatorial collective to share their insights and experiences with Hamish Sawyer, Artistic Director of NorthSite Contemporary Arts...

_card.jpg)

_card_Crop.jpg)

_Card.jpg)

Bisma (2023)_Card.jpg)

2018_watercolour and gouach on tracing paper.jpg)