Aldo Iacobelli began his artist's floor talk by drawing attention to the architecture of the Experimental Art Foundation gallery. Discourse concerning the space of showing immediately places in contingency the idea of 'showing a collection': if the works are immanent to the space in which they appear, where then are the limits of the frame which define the works, as art, and as architecture?

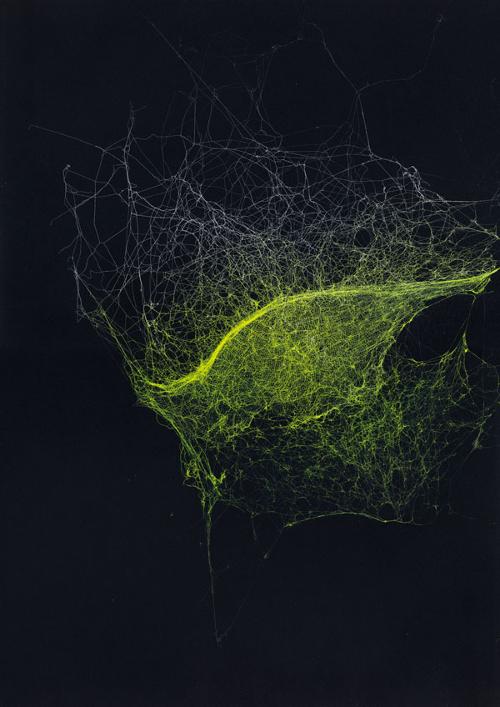

Within the gallery is a refreshing emptiness, not by virtue of a lack of works, but by the palpable sense of the space of the work; the space of connections and relations. The walls and ceiling(s) are painted a particular white, indivisibly matching the white paint of the hung works which thus diminishes their framing. Furthermore, the gallery lights are turned up high, washing out architectural features, leaving hard, but orchestrated, shadows that resemble painted lines in three-dimensional space. The only other colour prevalent in the six works shown, a Moorish-influenced viridian green, becomes that which holds individual works in place. This green is a directional device which draws the eye from one work to another. But it does this without stopping; greenness fibrillates in peripheral vision, destabilising the human as the seat of perspectival vision.

Upon entering the gallery, the eye is drawn to the shadow line of a ceiling bulkhead that conceals the air-conditioning register which throws vision to the far end of the space and down a new full height wall; the very same trajectory by which one perceives a driven ball across a golf course onto the greens. This architectural move conjoins the reading of the space and a work, namely Hole 7, 455 metres par five with a small amount of difficulty, located at the end of gallery, with its glazed ceramic white golf ball and tee placed in the middle of the vast (also newly painted) grey floor (there were bets as to when it would first get trodden; never mind, the artist made spares).

The full height wall at the end of the gallery flanks an opening of two metres, which matches a two metre space back at the entrance to another full height wall, the latter designed to reveal a two metre portion of the much larger work Manises railway station, made up of 360 individually painted canvases resembling decorative tiles. The geometry of the architecture is not informational nor organisational, but a potential for a material poetics: it opens the space of conversation, propensities and propinquities, that arrive not only from inherited conventions and hierarchies, but from timbre, nuance, accidents and hearsay. Herein also lies a role of the curator, Linda Marie Walker, writer, artist and academic: to keep company, with sympathetic exchanges and a friendship in relations; to be ready to welcome whatever comes.

Iacobelli's signature sense of a quiet unease is present in the show; this is the political in the work that is not didactic but enacts a redistribution of sense. The work is generous, it allows breathing, and there are many readings. A disjunction of scales brings us out of complacency, giving pleasure, through aesthetic labour upon the ordinary: the miniaturisation of the golf green; the enlargement of the fabric pattern in My mother does not speak English, and of a domestic clay vessel to almost human size; the faithfully scaled reproduction as paintings of decorative tiles; and the incommensurately long name (28 words in Italian) for the smallest work depicting grubs. And within the institutional walls of the gallery and the artificiality of whiteness as (back) ground, the land (nature) in green is framed, held in suspension, and speaking of (its) sustainability: the leaf motif frozen in the baroque fabric, its abstraction in Moorish tiles, grub borings reveal green life within the white walls, and the banal but ominous lawn behind the swing, it seems as though the wall grabbed the land and grabbed us too.