This exhibition launched the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art into a world which may not be as wonderful as we would prefer. Erica Green's selection of artists and works mixed certainty with uncertainty. It contained wondrous things but the portents were mixed. In a previous age where the world could be represented by a Mercator map projection it remained possible to envisage it as a series of landmasses separated by water and neatly divided into national principalities. The later 20th century unraveling of the once Austro-Hungarian empire, then the crumbling of the Soviet empire sowed the seeds of uncertainty about national borders being fixed and inviolable. More recently the concept of the world as a biosphere in which humanity as the dominant species shares common futures and fates with other species and environments has inflected the practice of a diversity of Australian artists with strategies aimed at getting the viewer to re-imagine the present world and its fate.

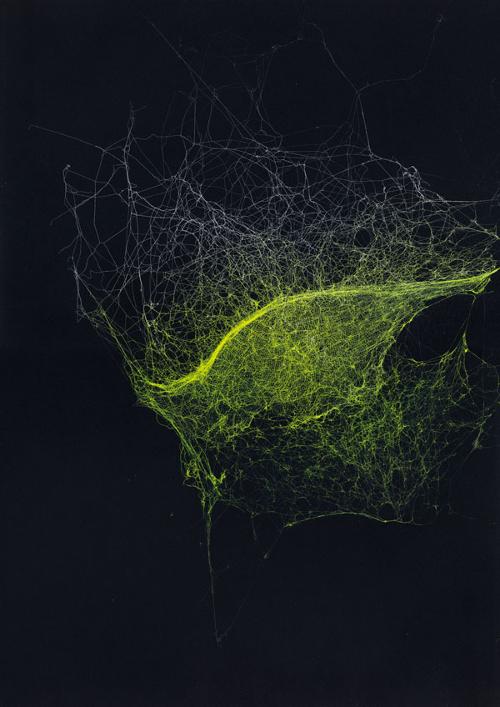

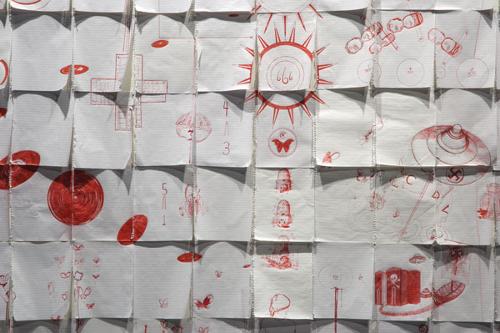

The strength and interest in Wonderful World lay in its ability to create a sense that the diverse works had things to say to each other. In the lower gallery area one of Jon Cattapan's 'mega cities' hung alongside a city-theme video by Daniel Crooks. Facing these works was a large multi-panel landscape by Philip Wolfhagen. Crooks' video and Cattapan's painting along with Narelle Autio's The Place in Between photo series incorporated notions of liquidity but in Autio's imagery, liquid was something arrested or confused as a body plunged into a pool is translated into mutant form. Crooks' videos city source material created a hall of mirrors experience in which people and trams materialized like fairy floss while Cattapan's ciphers spanned their city effigies with traceries of lines which resembled power leads and computer circuitry. These various images seethed with implied malevolence or disturbing ruptures; Crooks' video offering the all-seeing black bud eye of a CCTV camera and Cattapan a volcanic lip view into the hot, toxic passions, intrigues and global connectivity that pulse beneath the comforting everyday world. Wolfhagen's liminal clouds also spoke of liquidity but in a Romantic language that intoned awesome dread of an aspect of nature as a grinder of bones, a persona reinforced by the presence of James Darling and Lesley Forwood's rendition of a river system, composed of bone-like mallee roots. In the company of these works and particularly when seen through the prism of Cattapan's forcefields of colour blooms and patterns, the heraldic striations and roundels that defined Ningura Napurrula's depiction of her country and its ancestral history, contradicted any reflexive reading of this image as 'Aboriginal art' but rather as conceptual circuitry. For a moment it was possible to believe that all the works in the room were humming with shared secrets about the true nature of the world 'as everything'. In the adjoining cinematic space Simon Carroll and Martin Friedel's film History of a Day wrapped the viewer in a series of 'days' which for all their restless revolving, gyrating and morphing, insinuated through repetition the idea that despite the sensual seductions of cinematic imagery, the human imagination must have stillness in order to reflect and understand. But was it the kind of desired stillness found in Anne Zahalka's subverted (perhaps contaminated?) museum dioramas? Here the cold comfort of threatened or even extinct creatures 'captured' in typical pose and environs was given an added chill factor by the presence of predatory helicopters or rising seas. Or was it the kind of stillness that emanated from a reading of Robert MacPherson's nesting boxes as silent witnesses to vanishing species? In the ebb and flow of fearful wondering Susan Norrie's epic multi-screen Undertow pitched the delicacy of fragile hope and the bloom of youth against apocalyptic fragments of human hell and environmental damnation. Wonderful World marked the Samstag Museum's eruption within the cultural landscape with the stealth of lava on the prowl.