Indelible is an affectionate celebration of the passing of youth. In creating this exhibition Sandy Edwards has fashioned a complex, diarist tapestry of colour photographs of people central to her life – women, men and especially children.

Visitors entering Edwards' display of large, immaculately printed colour photographs in Stills capacious gallery were met by a floor-to-ceiling, free-standing panel containing tightly cropped portraits of a small boy with golden hair. The boy's face, inexplicably, was painted bright blue.

The only variable element within this tightly structured visual grid was the boy's gaze, which strayed from oblique disinterest to disconcertingly direct eye contact with the viewer. There seemed a light-hearted suggestion in these photographs that this boy somehow belonged to an alien species – a playful inference by Edwards that perhaps youth is intrinsically otherworldly

Close attention to structure continued throughout the exhibition, with each panel, (or wall) containing clearly defined themes – photographs that either called attention to significant details within a scene, presented groups of unposed, but complicit portraits, or occasional observations of startling, elemental beauty.

One Edwards image haunted me for the ridiculous ease with which it held my attention as I wandered towards the most distant corner of the gallery. (I frequently start reading books from the last pages and often find myself drawn first to the end of exhibitions)

With an illusionist ease Andre Kertesz might have envied, Edwards photographed a large black beach ball floating in a jade green swimming pool. In Edwards' composition the black sphere sits on the surface of the water, as heavy as Jupiter. At first glance this photograph's blue and black-hued simplicity evoked instant, surprising thoughts of sculpture, geometry and astronomy. Nearby, an image of a bush fire added further elemental power to Edwards' exhibition.

But it was Edwards' photography underscoring the passing of time that I found most moving. By isolating images typical of the thousands of apparently trivial moments that comprise experience, Edwards addressed photography's elegiac nature.

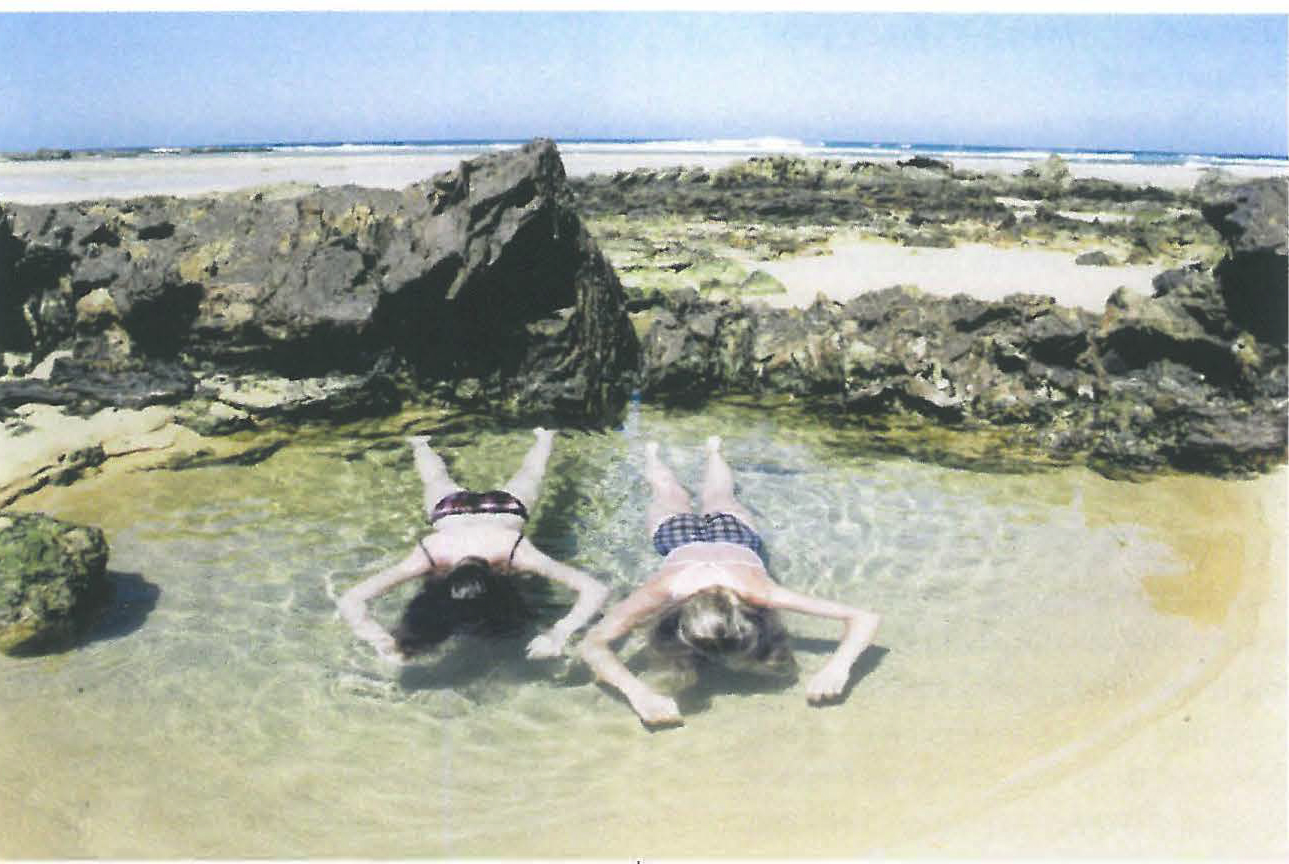

In one especially resonant image, two young girls in swimsuits lay prone in a rock pool on the edge of a beach, their backs warmed by a summer sky and faces and torsos half-submerged in seawater. Watching the girls' parallel fascination with the contents of the pool, I was entranced by Edwards' evocation of a friendship formed in the heat and light of summer. The visual authority of this photograph grew as I watched.

This was the kind of thoroughly artless image that propels viewers towards memories of their own childhood – of bonds formed when days at the beach seemed to last forever.

I saw this exhibition with a renowned Australian documentary photographer of fierce dedication to the cause of political change and he suggested there was an overall softness in the way Edwards expressed her visual beliefs. Seeing these pictures again after several months, it is impossible to deny there is indeed a softness, even delicacy in the way Edwards portrays her world. Photographs in Indelible however, show this photographer's consistent response to her friends and family and an unquestioned honesty in the way she celebrates simple, universal themes - such as the games played by children and changes we witness in friends growing older.

However, I did wish occasionally to see more of the uncomfortable counterpoint every parent knows – rushes of uncontrolled love, pain or anger from children, for example – moments when family life veers from the lyrical to the less palatable.

Ultimately, however, this exhibition shows how faithful Sandy Edwards has remained to her talent. Her vision is that of the simple observer, a diarist with a camera, preserving fragments from departed days. And the ease and complicity of these photographs show that she was a welcome guest at this party.

Technically, her response as a picture-maker was simple in the extreme. Compositions are economical with rarely the awareness of any particular lens imposing its perspective. Her subjects, more often than not children, are consistently observed with affection and respect.

Previously I was more aware of Sandy Edwards as a photographer working mainly in black and white. Her collaboration with author Gillian Mears on the book, Paradise is a Place (Random House 1997) produced imagery of a far more visceral, classically photojournalistic nature. This exhibition suggests another book may lie waiting within the sensuous colour of Indelible's images, with the addition of appropriate text to complete the latticework of relationships suggested by these photographs.