Internationalism is currently a central perception in contemporary Australian art. In recent months in Melbourne the conferences of Empires Networks and Ruins and South 1 have presented the artist as no longer white and English-speaking. Even the framing paradigms of the Sydney Biennale include a geographical perspective where the North is the hemisphere of reason and authority and the South the hemisphere of the emotions, sensuality and laxness. Cross-references are currently consciously global. On cue Heide has mounted a cogent and focussed comparison between two major living artists: Gordon Bennett from Australia and Peter Robinson from New Zealand. Drawn from the conjunction made by New Zealand curator Pennie Hunt in her masters thesis, the touring exhibition Three Colours is the first public gallery alignment of these artists.

The partnership is thoroughly convincing in the political content/context. Whilst there are significant differences in the individual oeuvres, there are uncanny similarities between two artists who had had no admitted contact, but shared interest in certain historic sources such as Basquait and McCahon. Both oeuvres demand 'reading' in light of various current forms of thinking: art history, art theory, postcolonialism, race, identity, modernism, postmodernism. Both artists partake of and yet parody major intellectual projects, mapping and mirroring recent thinking around race and nationhood. Bennett and Robinson's recent phenomenal successes suggest that they encompass/express a need/desire in current experience.

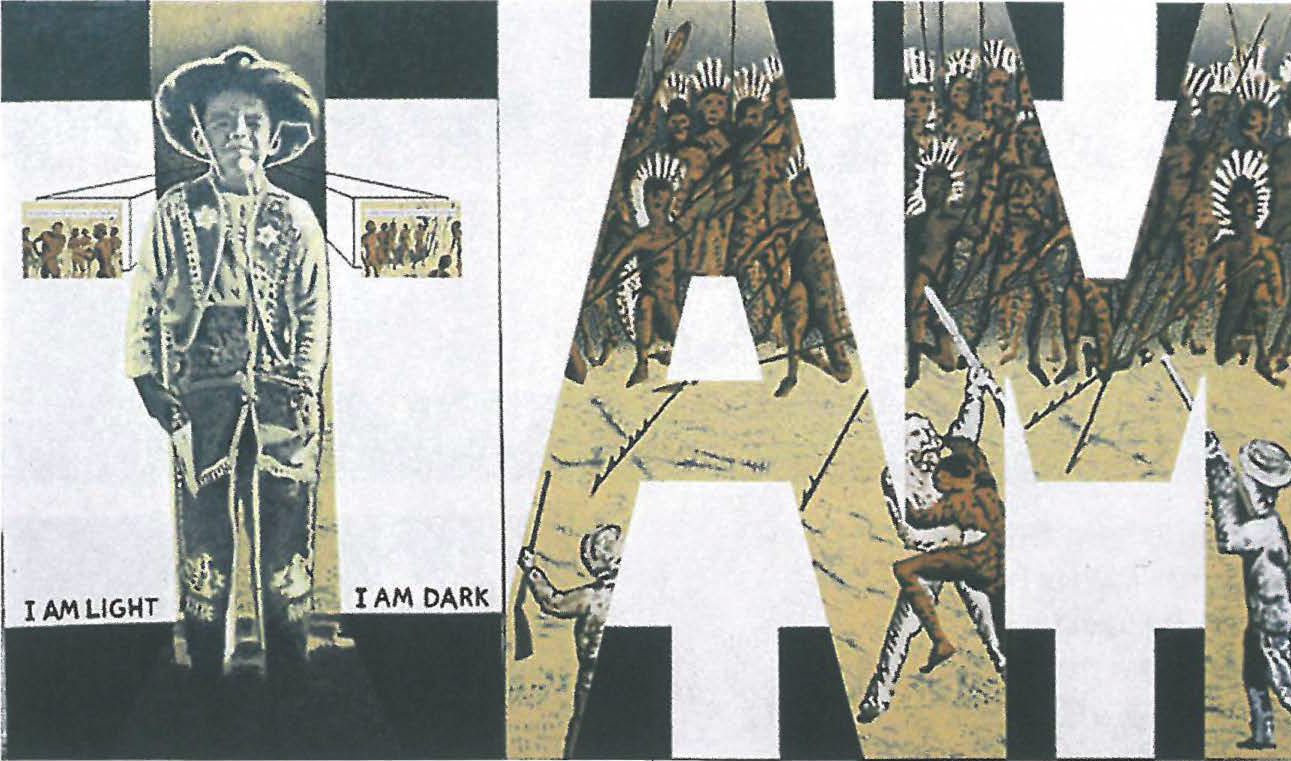

Bennett's Self Portrait (Ancestor Figures) 1992 and Self Portrait (But I Always Wanted to be One of the Good Guys) 1990 may well contain all that a future generation wishes to know of our era, just as Shearing the Rams was believed in the 1970s to speak the truth about historic Australia.

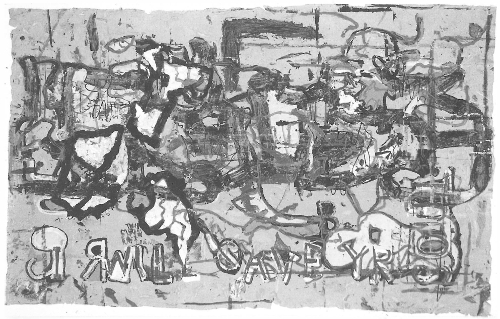

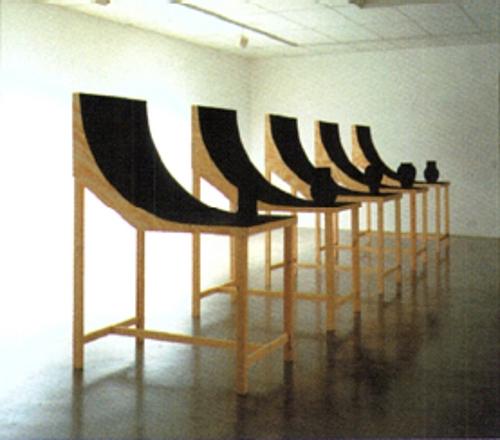

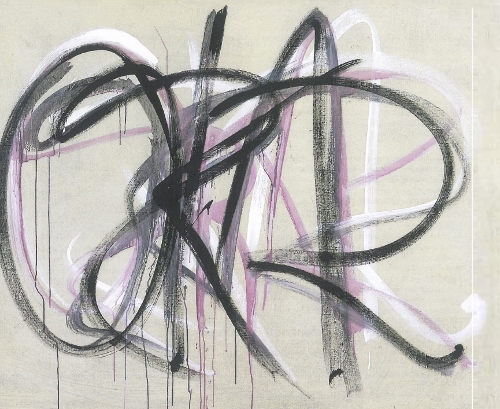

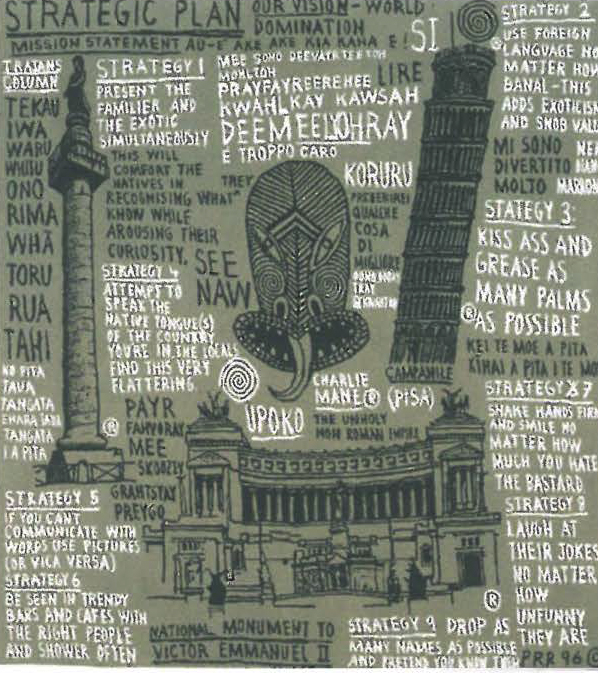

The authority of these impressive works holds the gallery space in thrall. Bennett and Robinson dexterously range from the mimetic to the expressionist, mimicking many distinct genres and periods in pursuit of their narrative goals. Frequently both oeuvres overlap with references to scarification and wounds in the paint surface, art historical quotation, ironic questioning of the use of the exotic. Both reference Colin McCahon – an artist with titanic presence when evaluating the significance of contemporary art from the South and with whom any internationally ambitious artist from this region has to engage. The provocative comments painted in a rough handwriting on the canvas, the need to read these paintings intently as text – the direct exhortations to the viewer – the communication about the artists' own dislocation against a racist and alienated society further cross over between oeuvres. This is an exhibition of essentially declamatory art.

Whether his works are seen as individual physical entities or collectively as cultural phenomena, perhaps due to cultural familiarity, Bennett's oeuvre appears to be more consolidated and sober. In comparison to Robinson it acquires a certain solidity and does not lose out for this weight and consideration as project.

Bennett achieves a de facto Edwardianness, an elegance of large scale, a stability and inevitability of visual and thematic content, firmly focussing its accusations to white Australia. There is a public ritual about Bennett's artworks. Each one, like the Mona Lisa, hangs in the gallery replete with a history of the first viewing and the innumerable survey exhibitions and reproductions through which the meeting is replayed.

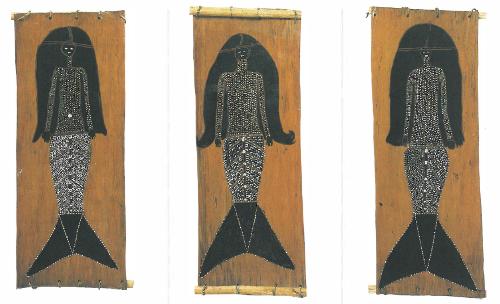

Robinson's works – less bound by ceremonial associations than Bennett's for an Australian - cover a wider stylistic range within the underlying consistency of the political engagement. Perhaps the shining facets of its versatility reference his northern hemisphere reputation. There is a certain YBA facileness, even overt smartness, in the constant spinning out of novelty. Robinson morphs into installations, the abject, the self consciously childish and faux naive. This is tatty, grungy, provocatively anti-art, a little superficial, in comparison to the 'grand manner' of Bennett's museum/historical pieces, so excellently crafted both as art and as thought.

Fagtime 2003, a Mr Potato-Head in polyurethane, and Serena Lees' Inflation Theory 2002 a drawing of a soft porn star with mammoth breasts, indicate a sensibility that ranges more widely than Bennett's focussed narrative. The shadow of the Saatchi brothers and their protegées such as Emin and Hirst just does not leave my peripheral vision. It could however be the Australian gallery visitor's lack that the cross references of content are less easy to read.

The meeting of the two artists not only consolidates their significance in relation to one another but marks a new willingness for Australian art to look outwards with maturity rather than anxiety and dependency.