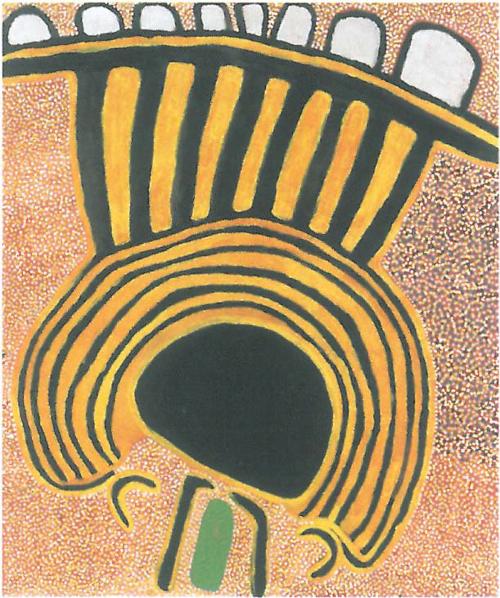

The black, wedge-tail eagle 'Warridah' is a significant creation being for Julie Dowling's family and its proud profile is a central image amongst the collection of paintings in her show at Artplace. Another large work shows her great grandmother standing resolutely in the landscape casting a bird-like shadow in the moonlight - family and country merging together.

As a Badimaya/Noongar artist from Western Australia, Dowling's connections back to land and country are vested in her family and their dispossession from their traditional lands around Paynes Find and Yalgoo in the Gascoyne region is the sub-text of this exhibition.

Many of the paintings document the outcomes of this loss of ownership and the way it has impacted on her family, yet the underlying urgency of her message is revealed slowly through the subtle interplay between image and text. By reinforcing that the personal is always political the intimate familial activities of her life become a statement of the broader political issues of sovereignty, reconciliation and nationality.

In The Gauntlet for example her grandmother and grandfather take a trip into Perth in the fifties to buy new clothes. They have their kids with them holding presents and she is pushing a pram, but they are trapped within a net of white eyes – the gauntlet of the disapproving white gaze. Dowling tells us in an accompanying text that the family moved to the country just after this photograph was taken to escape the enforced curfews and the attention of Native Welfare.

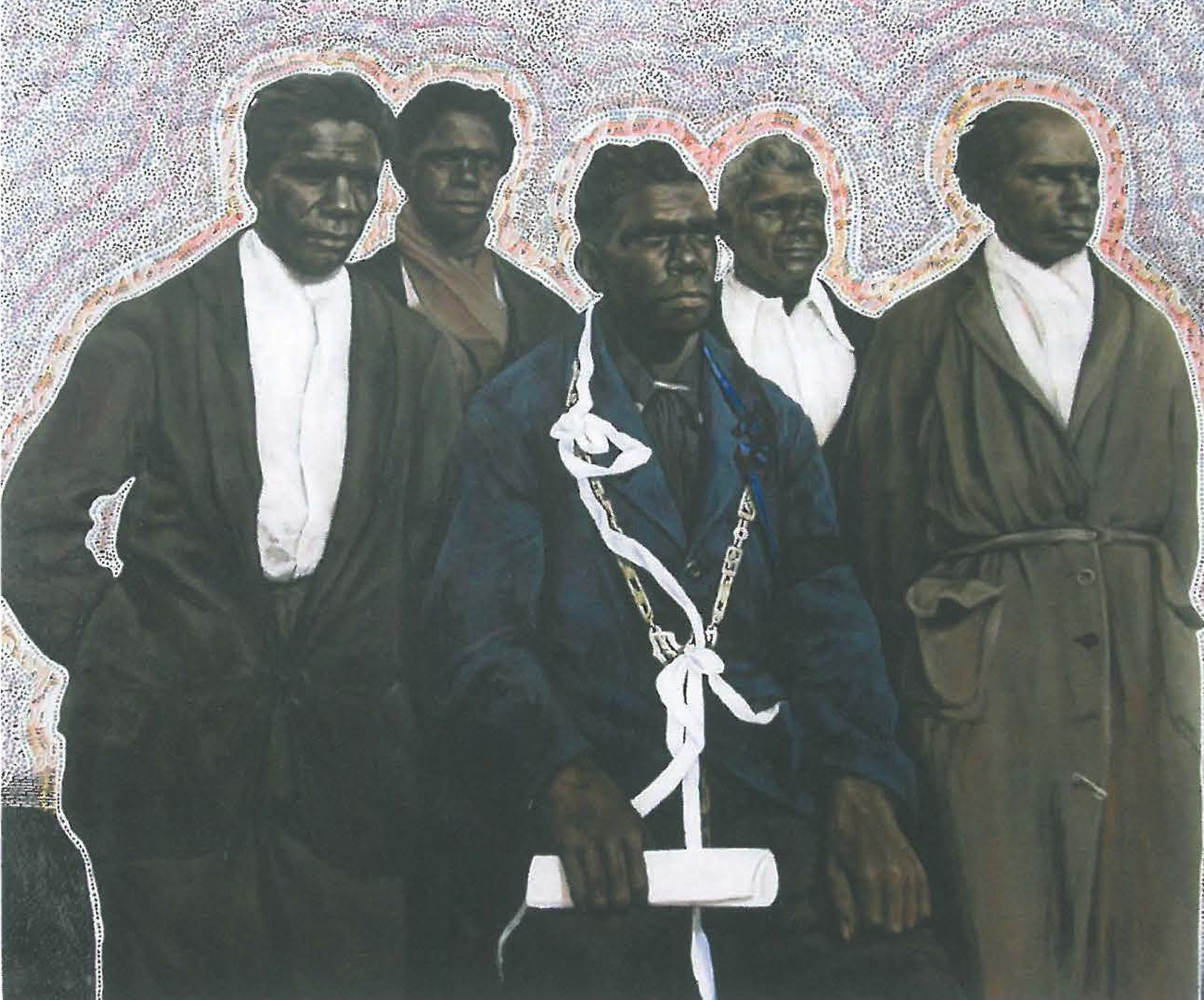

Another compelling image and one of the most beautifully painted works in this show is The Citizen King, which records the success of Beaufort Diner who won his citizenship as a prize for a boxing championship and as a consequence was recognized by white Australians as a 'king' of his people. Seated stiffly with his medal round his neck and his friends behind him, including Dowling's uncle George Latham, he is presented as a heroic figure, offered the approval of the dominant culture because of his athletic ability. Has anything changed the artist asks, like our current football stars 'our men are still measured for their acceptability by their physical prowess rather than for something more important'.

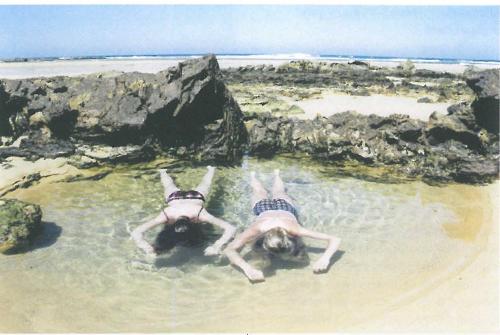

Dowling is a powerful image-maker who draws together disparate strands of information and weaves them into new interpretations of our history of relationship between white and Aboriginal Australia. In The Boat People for example, she documents an incident when she and her sister went to live with her grandmother. In the kitchen, in front of the wood fire, the girls are being bathed in a pink plastic bath given to the family at the hospital because they were poor. The blue towel handing on the line strung above the fire is the other sharply contrasting colour, the rest of the image is like a black and white photograph with the strong form of the Christian cross positioned directly above the heads of the three figures.

The shape of the bath reminded the artist of a boat and because Aboriginal people called non-Indigenous Australians 'boat people' and because this photograph was taken at the same time as the Vietnamese boat people were arriving in Australia, Dowling sympathized with their plight by acknowledging her own white heritage and accepting that she too had a 'touch of the boat people' about her.

The poignancy of the image is heightened by the reference to a hand coloured photograph, inflected with special care and consideration, because the colours sit uneasily together creating a sense of discontinuity and separation. This sense of disjuncture is a powerful and recurring image in Dowling's work.

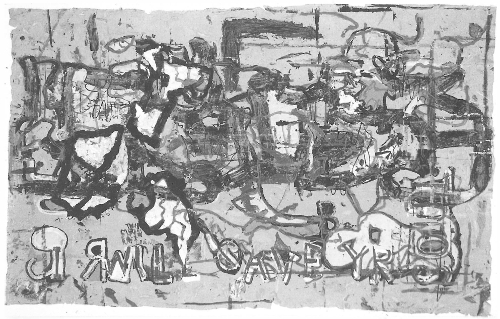

There is always a wonderful series of portraits in every Dowling show and this one is no exception. The Dispossession Series comprises five large paintings of Julie and her sister Carol, her Mum, grandmother and Great Uncle George. They are pitched in bright colours but the scale of the works and their intensity creates a powerful sense of humanity, of human suffering and most importantly of resilience and strength. Each painting comes with a text imbedded in the coloured background and in the case of Nana Molly it reads 'I cannot pay for the land where my ancestors are buried' and for Uncle George 'Give me back my land'. All are staking a claim for Warridah Sovereignty.

Julie Dowling is one of the most eloquent voices in Australian Indigenous art and this current exhibition reinforces her position as an important spokesperson for Aboriginal Australians in the current debates surrounding reconciliation.