On the very day that Barking Up the Wrong Tree, a challenging collective and collaborative initiative was opened to public scrutiny Peter Garrett, former Midnight Oil frontman, ironically eschewed an earlier activist radicalism by accepting a majoritarian, two-party preferred model of political advancement.

This exhibition, co-curated by Stephen Mori, Felicity Wade and Raquel Ormella, is a joint initiative between Sydney's Mori Gallery, The Wilderness Society (NSW and TAS) and the Hobart City Council. It presented a wide variety of works by regional, national and international artists, activists and collaborators, working in and across a variety of media.

All involved expressed overtly and unequivocally their concern for the future of the endangered timber stands, giant eucalypts and native wildlife of the temperate rainforests in Tasmania's Styx Valley. This area remains threatened, under the current Regional Forest Agreement, with despoliation and degradation through the continuation of controversial clear-felling practices by Forestry Tasmania.

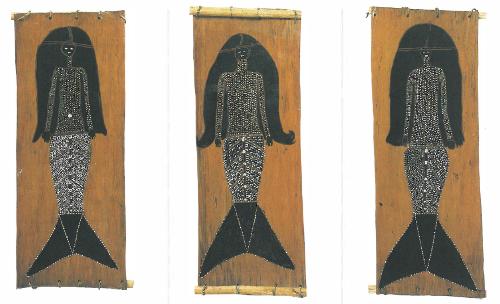

Diversity is the key here: with past Archibald Prize winners, recent Asia-Pacific Triennial participants and current Biennale of Sydney inclusions rubbing shoulders with regional names, relative unknowns and dedicated contributors to group projects facilitated by local artists.

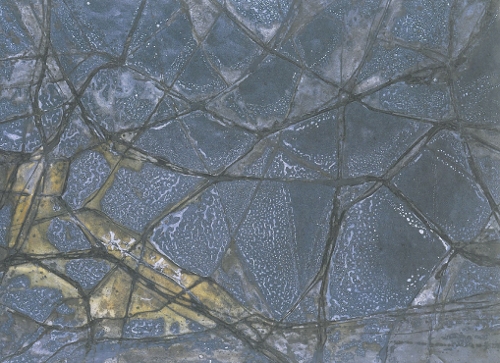

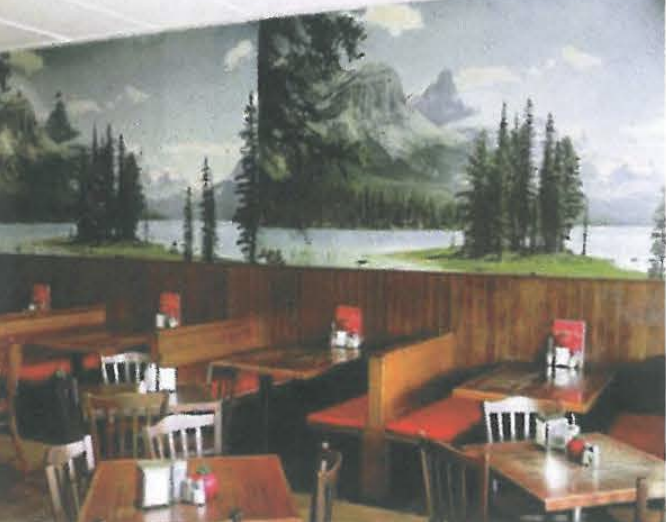

Thus, Cherry Hood replaces her successful oversize watercolour portraits of young males, with an image of a visitor's car dwarfed by the sheer height and presence of the trees standing either side of an access road. Similarly, Joan Grounds isolates the potent symbol of the axe from an earlier work, but this time has smeared it in bitumen and constructed upon it delicate, insect hive-like structures from wheat-paste and paper. Daniel Malone offers up two conceptual pieces, one a layered pun on Tasmania's past and future, replete with kitsch postcard imagery, the other a large scale video projection.

All works on display, however, from the immediately graspable to the more obtuse and conceptual, constitute a potent point of departure for those fortunate enough to view them.

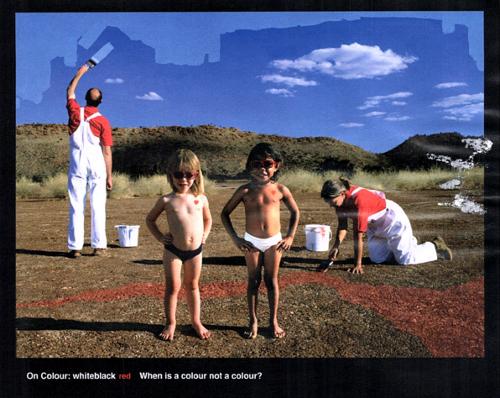

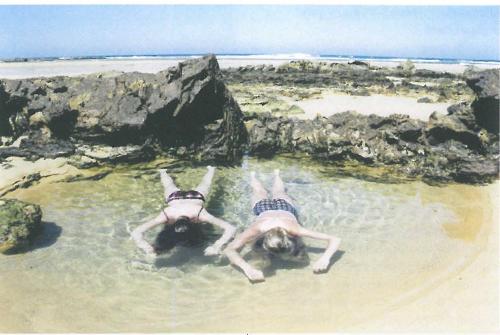

Relatively straightforward statements with broad appeal such as the brightly coloured, yet tragically elegiac landscapes of Peter Gouldthorpe, Susan Norrie's starkly monochrome text paintings and the photodocuments of Catherine Rogers, sit appropriately alongside the reportage work of Fairfax photographer Dean Sewell and the pointedly cynical and ironic poster of culturejammer, Neal.

The human face of environmental struggle is arguably best discernible in Jo Boag's Global Rescue Station Faces; diminutive felt and cotton 'portraits' of activist volunteers that sit like badges of honour on an old polar fleece and beanie, 150cms from the gallery floor. (The original subjects having been perched 65 metres from the forest floor for months at a time). Likewise, Raquel Ormella's six haunting images of unpeopled Wilderness Society office rooms and Warholesque facsimiles of newspaper pages noting activist media events - such as the Rescue Station and the textual hijacking of the maiden voyage of the Tasmanian Government's Sydney-Hobart ferry, the Spirit of Tasmania - remind the viewer of the humanity of their subject matter. These works document the thrifty utilisation of often scant levels of resources, and high levels of organisation and commitment.

To focus on the most well known, established or credentialled participants is, however, to crucially miss the point. That well established artists accompany local names, industrious activists and large groups of participants such as the many involved in Dawn Csutoros and Helen Douglas' Tree-Hug Project, is the real measure of this exhibition's cultural importance and value.

In the perpetual contest of meaning that characterises the world of politics, the sustained public circulation of persuasive imagery and text, irrespective of its ideological basis, underpins all attempts to justify and sustain, or to critique or discredit, the continued implementation of governmental or corporate policy.

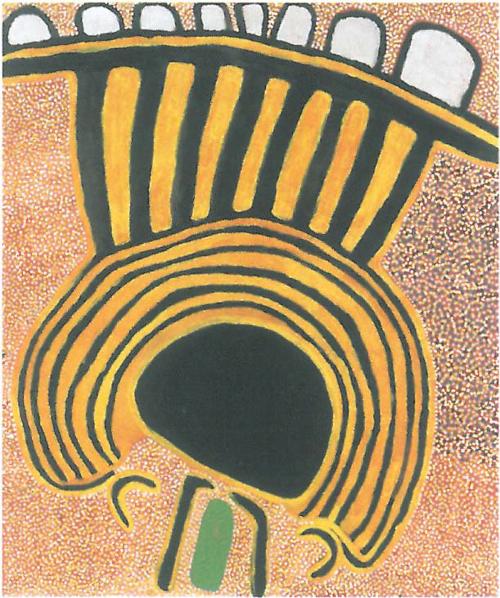

Less starkly agitprop than one might first assume, the sheer range of artists and conceptual and visual strategies on display would seem to strongly suggest that any purported 'green heartland' can no longer be identified purely on the basis of numerical electoral representation in the southernmost Australian state.

A diversity of content, media and conceptual approach operates simultaneously here as richly allusive buzzword, active strategy and vehicle for the rejuvenation of the political, social and cultural spheres. Barking Up the Wrong Tree calls strongly for an end to the maintenance of such false separations, for an end to political, social and economic reductionism, a blurring of the binary; a re-valuation of nature via culture.