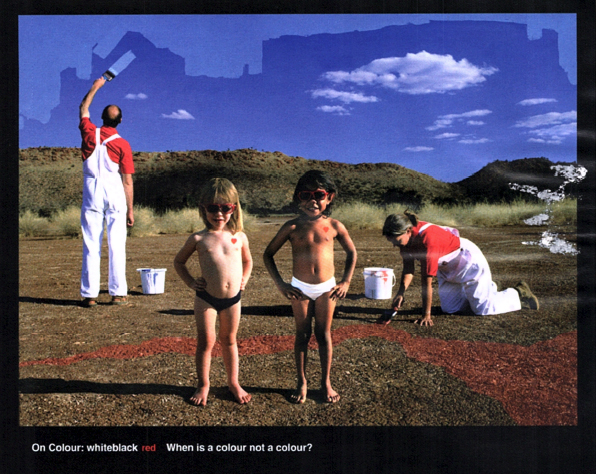

The duality of black/white, as the terms are used in the Australian media, is currently a highly contested area. Sue Richter's exhibition On Colour: whiteblack red investigates the underlying language and history behind this binary opposition and forces the viewer to confront his/her own understandings of the terms 'white' and 'black' as they are used in daily discourse. But she also provides us with a way forward that subverts this historic duality of language.

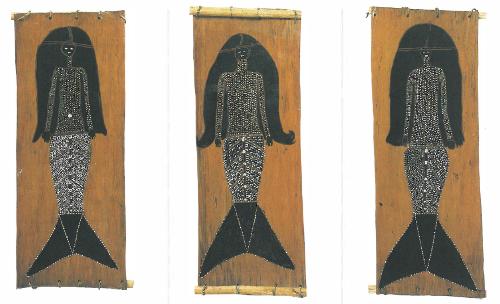

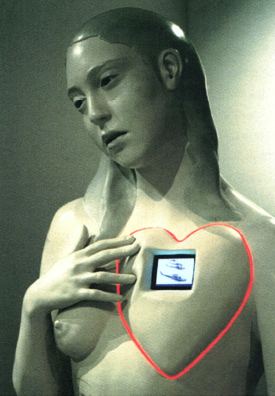

The installation consists of an opalescent female nude on an open half-shell, two digital photographs, life-sized photographs of two smiling young women, (one Aboriginal, one non-Aboriginal) a booth with text and chalk boards, and a wall relief of an outback red dirt road with text. The nude/Venus has a small video monitor set in her heart region, which plays the appalling and beautiful Valkyrie scene used in the film Apocalypse Now. There is a series of faint images tattooed on her body. This work attracts us through its cool pure white beauty, while we are confronted by the shock of the video, its 'heart of darkness' set into its heart. Do we read from this that all purity contains within itself its own darkness, its own destruction, or is this an alien quality imposed on it? The tattoos on the figure reinforce this sense of applied darkness/evil layered on to the female figure. The work foreshadows the Iraq war, with its video/TV footage of the destruction yet again of a 'dark', 'irrational', 'brutal', enemy, to be vanquished by the forces of 'good' (Christianity) 'reason' and 'light' in the name of (whose?) freedom, for the reward of its black gold, oil. The photographs from Abu Ghraib prison have shown the world the futility of attempting to portray one group as 'good' and another as 'evil' - the heart of darkness lies within us all, even inside a young prison guard.

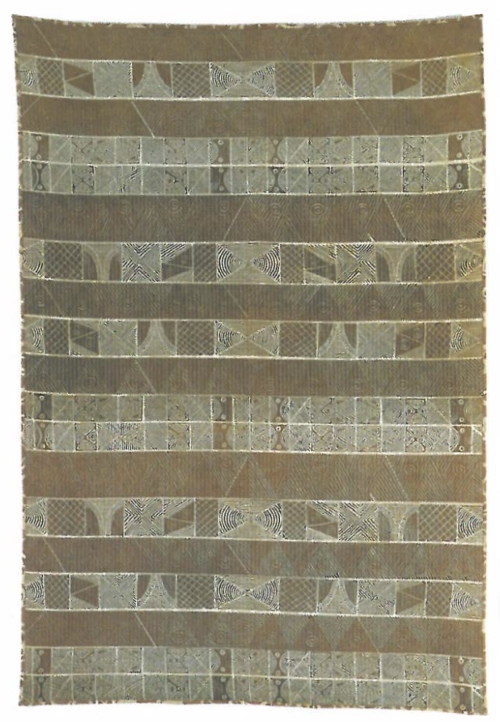

Richter is interested in the way that oppositional meanings have been attributed to these words, accreted onto them over centuries like tattoos on the skin, and the ways in which Western thought has encouraged and promoted the separation of the objects and people represented by these words. She begins her reading of these opposites by asking us to consider the many meanings attributed to them. The viewer is forced to confront his/her prejudices. At first view the various forms and images of the installation appear to be hammering repeatedly away at our preconceptions. Black/white, white/black, dark/light, emotion/intellect, primitive/reason. It is difficult to read these images as merely representations of binary opposites. They have a shocking power - we are not comfortable being forced to confront our reactions to these words. There is also a contrived kitsch about some of the work - the tiny bleeding hearts, the artificial rose which references the rose tattooed on the nude's thigh, and even the red glowing cord which is placed around the 'heart of darkness' video image of villagers fleeing in futile desperation while they are mown down by an avalanche of helicopter gunships. The kitsch satirises its own seriousness, and provides an ironic distancing mechanism.

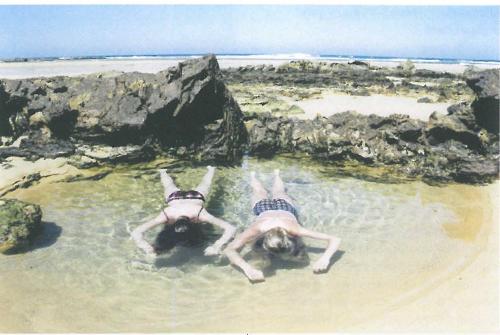

The second photograph provides the sense of hope that Richter offers. We are shown a view of a future world in which the duality of black/white has lost its power. We are able to move past these terms with their terrible histories of power/gender imbalances to a future of unity, represented for Richter by the word red. Set as the work is, in the red heart of Central Australia, with the endless tourist 'views' that this implies, Richter interrogates the artificial black/white duality, while also acknowledging that this duality is reinforced by the stereotypes of Western thought. The 'Red Centre' is both the tourist stereotype with its red 'heart', and the lived reality for its residents. While the duality of Western thought since Descarte's mind/body split has created the opposition of 'the other', the one that isn't 'us', Richter shows us clearly that there is a way forward, a coming together of the opposites, so that we who live with Australia's constant casual racism, can see how a deeper understanding of language can help us move together into a partnership and friendship, past all oppositional dualities.