Sound is commonly registered as an everyday phenomenon of ethereal transmission, its intensity a measure of distance and receptivity of the ear. Indeed, it’s only when the material relations change drastically, for example, when going under water, that sound distorts, behaving differently, prompting us to question its qualities as a medium for art. Silence, also, is so often taken for granted. Only rarely do we listen for it to realise that silence is rarely actually silent, but only less noisy.

This exhibition curated by Caleb Kelly, first shown at the Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA) in 2018, commenced its regional tour at the Manning Regional Art Gallery in Taree, where I encountered its material investigations for the first time. Its creative agendas questioning the material qualities of sound by way of artistic exploration go beyond the orchestral qualities of timbre, pitch and resonance, beyond the codes of standardised instrumentalities, and beyond again the domain of found and remixed sounds of the early modern pioneers of sound art, and the late twentieth-century practitioners of sinecore and other computer-generated sonic phenomena.

Instead, the sonic territory of Material Sound is predominantly body – human bodies, celestial bodies, the bodies of forest and furniture. Pia van Gelder’s Recumbent Circuit presents as a kind of abstract plywood chair, into which your body is comfortably loaded with back and leg support. Thus physically situated your body itself becomes an agent of electro-chemical and electro-magnetic variation, a resonating and chargeable mass which through the completion of the body’s electronic circuit from right to left foot – made possible by the two conducting metal sole-shaped plates upon which your feet are placed – permits the amplification of the electromagnetic currents coursing through the body. By tapping your feet, lifting your soles on and off the conducting plates your own body capacitance can be played as a series of beats.

One of the “chairs” was tuned to a deep base pulse – the sound appearing to modulate with differences in body mass. The other chair was set at a higher register, permitting two players, each occupying their individual seats, to create a work of complementary body beats and tones, in effect tapping the electromagnetic body for its sonorous capacity.

If Recumbent Circuit was a work for feet, van Gelder’s companion piece Soft Synth No. 1, was a work for hands and arms, for the body contact of caress. Complementing the domestic setting of the chairs, gallery goers were invited to lightly stroke a wall tapestry of mixed fibres in the manner of petting a dog or a pony. Long curly fibers responded best, while the collective ensemble of the furnishings reflected architectures of mid-century modernist intimacy. In contrast to Recumbent Circuit, the sound of Soft Synth No. 1 was subtle, more akin to the soothing affects of white noise than the pulse like beats emitted through the foot tapping of the chairs.

The evident joy of engagement in van Gelder’s work stemmed from the rare activation of the body as a thing of material substance, drawing upon its capacity for electronic interference–disturbance–participation, a role to which human bodies are not customarily attuned. More usually domestic appliances are fitted with non-conductive insulators either to prevent the human body from electrocution by large voltages, or to protect delicate electrical equipment from the electromagnetic interference of the body, a natural low voltage conductor. But in Soft Synth No. 1 van Gelder’s interest lies in activating and amplifying the sound of such latent microcircuits between everyday things and the human body. Through touch the body becomes a direct agent of electro-chemical communications, which, without amplification, would have remained subsonic.

On the opposite wall a different kind of plywood construction has left the domestic register for the forest. In Vincent and Vaughan Wozniak-O’Connor’s Radiata Studies the gallery-goer is taken deep into the topography of a Radiata Pine plantation, the source of the trees that are farmed for plywood. Over several panels the topography of a forest, with its hills and hollows neatly sculpted, has been digitally 3D-mapped in thick plywood. Edges blur at some distances as an optical illusion, but firm up sharp on close inspection, while an abstract text in black, laser-cut into the plywood, marks the positioning of the GPS satellite putting the forest under constant surveillance. This serves to remind of the expanding dominance of the visible. Nonetheless, the key drivers of the work pertain to a subliminal, secret forest language. Delivered through twin arrays of tiny speakers, gallery goers can listen in on the amplified sounds of the trees as they grow, experiencing the forest as a strangely sentient presence.

With Radiata Studies thus laid out across the room from the human-activated van Gelder work, a conversation of kindred materials is taking place, like a shared intimate electro-chemistry. Through amplification, the bodies of both people and trees – alive, growing, and electro-chemically functioning – are linked through a kinship of sound.

The remainder of the front room gallery is filled out by Vicky Browne’s vast display, Cosmic Noise, as if whole constellations had been charted across an unknown galaxy composed of copper, graphite and silicon. Shiny planes of copper stand in as planets and slowly rotate like disco balls hung from the ceiling. On the floor a similar disc is rotating on a small portable turntable whose needle arm periodically clips the sides of a pyramid-shaped planet suspended on a string, causing it to spin. This, in turn, drives the motions of nearby suspensions of other pyramid shaped planets. In a far constellation, at the back of the room, slowly turning lengths of copper converse with a small city of black mud-castle towers seemingly formed by dribbling wet sand through a child’s fingers. Oversized wind chimes, or dream-catchers, composed of graphite under glass, also rotate slowly in the manner of planets, and remind us that worlds can be fragile. The whole is a carefully articulated performance, an intimation of Pythagoras’s “music of the spheres” as tuned planetary bodies.

Yet, the overall effect is refined and restrained, the sonic elements subtle. Indeed, Browne’s Cosmic Noise is very, very quiet reminding us of the near silent science of astronomy. Two of the larger copper plates, in fact, function as muffled gongs. A length of thick rope ending in an oversized knot invites you to swing the rope and strike the surface of one, while a makeshift drumstick comprised of a stick and a ball of padding is purposely hung adjacent to the other. Swinging the strikers into the gongs generates soft, barely discernable sounds. Meanwhile, other tappings and tinkerings, rhythmically generated by the various rotating elements, punctuate an airy soundscape suggestive of how interplanetary distances could be imagined to sound.

Indeed, if van Gelder and the Wozniak-O’Connor brothers draw on the matter of living, breathing/transpiring bodies, Browne conjures interplanetary systems of the raw materials of silicon (glass), graphite and copper, all elements necessary to the conduction and transmission of electrical systems (the same trace elements residing in human and other living bodies). The sound in question across all three of these works would under normal, non-amplified situations approximate to silence. As such, under these amplified and imagined conditions we’re listening in on the material substances that drive and make possible the condition of life on earth, and perhaps continue on dispersed throughout the galaxies.

Though the visceral and visual aspects of the exhibition are certainly engaging, Material Sound is still best taken in through the means of slow absorption, by giving over to the necessary time for the sinking of the sonic elements into your body. The bleeding of sound from one installation to another has been exceptionally well managed in the resultant sound collage of Brown’s Cosmic Noise and Ross Manning’s Pixel Points, installed in the room at the far end of the gallery.

The combined experience builds up to the admixture of a complementary chorus. Manning’s installation relies upon classic Situationist détournements of everyday objects, using repurposed computer fans to set various pendulums in motion. Striking a series of seemingly casually placed material objects – metal domes of deconstructed bicycle bells, clay pipes, split bamboo and plastic caps from aerosol cans – the result is a variegated mixture of rhythmic and arrhythmic compositions. The heavier clocking sounds of wood and clay balance out the higher notes of the glass and copper chimes of the Browne installation. Listening to the two works as an integrated sound performance, in the way that listening is a complementary compositional mode to the visual, a deep correspondence of material origins emerges.

Nonetheless, the timbre of Manning’s plastic tops begins to stand out for its different tone. One could speculate their fossil fuel derivation sounds a different note in comparison to the metals, silica, earth, and matters of vegetative and animal origin. Thus through the sonic qualities of each of the material components, the Browne-Manning symphony draws you in to reflect on material origins. Without ostensibly signaling the compositional shifts in materials and modes of production in the Anthropocene era, a by-product of this intensive listening is to pick up on the false note of plastic, and to draw the contrast with the more ancient sounds of glass and copper chimes, and those of struck bamboo, earth and clay, sounds with which humans, indeed the forests, cohabited prior to the Industrial revolution and modernity’s century of plastic.

Such thoughts arise in the drifts of association that flow alongside the unfolding soundscape. Perhaps they are an illusion. The associative process could be described as occurring through synesthesia, each note recalling a visual memory of the individual substances struck.

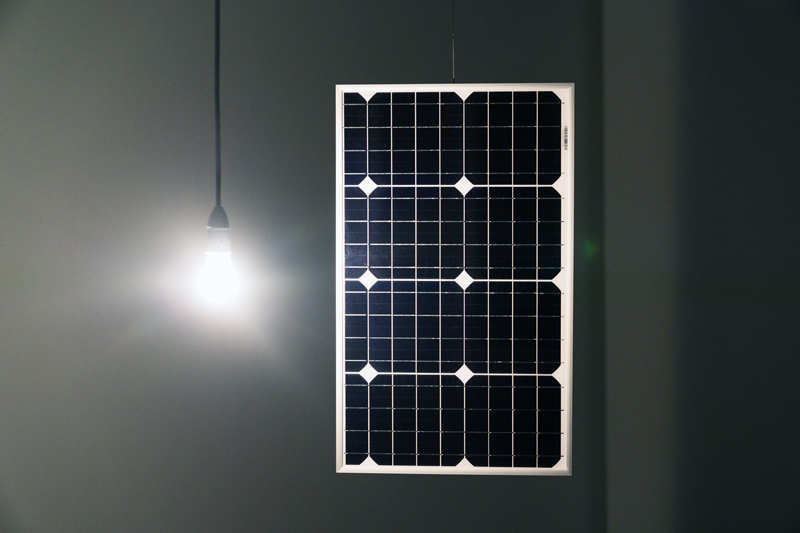

Peter Blamey’s installation of Single-Planet Orrey and the Energetics of Stored Moonlight more directly offers a corrective to the Anthropocenic damages of fossil fuels with twin technological fabula. The first is faintly ridiculous, in its suggestion of powering Earth by moonlight. Placing a video of the phases of the moon opposite a solar panel he creates the illusion that moonlight is producing the fluctuating current running back from the solar panel through the power cord to the grid. A sonic component of low beeps tracks the apparent strength of the current, with the loudest signals generated by a mirror image of two moons. Lightly tongue in cheek, Energetics of Stored Moonlight could also be read as responding to the hype surrounding the harvesting potentials of the renewed space race. Not enough power? Put another moon in orbit.

In Single-Planet Orrey, a single naked light bulb, representative of the sun, appears to be generating the energy sufficient to rotate a solar panel on its axis in the manner of the Earth’s rotations (in reality driven by the evident disco ball mechanism plugged into the mains). An obvious fiction, Blamey’s allegory is an exercise in wishful thinking, suggesting that without becoming a giant disco ball covered with solar receptors (such that sufficient receptors will always be facing the sun), the earth won’t turn and energetically survive.

The exhibition rounds out with more putting of your body into the interface of the artwork. Caitlin Franzmann’s Drawn Together, Held Apart reconnects with van Gelder’s use of furniture as a medium of bodily communication. If van Gelder requires the application of feet and hands, Franzmann has you kneeling on the carpet, cheek and ear laid down flush with the surface of the low glass coffee table. In effect, ear, cheek and glass merge into a listening apparatus as faint sounds of chanting, news and spiritual guidance can be dimly heard, thanks to the transducer speaker that has been inbuilt into the table. As such, the use of glass (silicon) as a medium of sound conduction also talks back to Browne’s glass dream catcher constellations, making the link from the domestic sphere to the stuff the stars and constellations are made of, the same shared matter.

Surprisingly, Material Sound is permeated by the interconnectedness of deep ecology. Perhaps this is an effect of deep listening to the timbre of electro-magnetic touch intermixed with more ordinary, intelligible sounds of nature and Anthropocenic technologies. Most remarkably the subsonic terrain of the electro-chemical and electro-magnetic is brought to resonate on the surface and extended to the stars.