Curated by Alison French who first encountered Aboriginal artists at the Araluen Arts Centre in Alice Springs many years ago and has worked in and around the field ever since as a writer and curator "Hermannsburg: echoes" in the landscape brought together historic works in the Flinders University Art Museum collection by Rex Battarbee, Albert Namatjira, Otto Pareroultja, Cordula Ebatarinja and others together with works by the descendants of Namatjira and his extended family and classificatory relatives in the region of Ntaria (Hermannsburg) made recently at the 'Many Hands' Art Centre in Alice Springs.

The work of Namatjira which shares the status in some ways of the work of both Arthur Streeton and Hans Heysen in being archetypal Australian landscape art also shares with them the overexposed situation of evoking placemats, cheap calendars and general jingoistic props so that it is sometimes very hard to really see the work. Namatjira is an Aboriginal art hero. His example, his fate, his experience of discrimination, his determination to do his work is role model gold. While celebrated (sellout shows, meeting the Queen and so on) as showing that a black man could paint/think/see as well as a white man his work was dismissed in the past by art cognoscenti as amateur watercolour rather than high art. It has however been suggested over the years first in Flinders University Art Museum’s 1993 “The Heritage of Namatjira” and then in Alison French’s 2002 “Seeing the Centre: the art of Albert Namatjira” at the National Gallery of Australia that, apart from his potboilers, his work can be studied more deeply as art that does encompass his feelings for his country and engages with traditional Aboriginal culture in its devotion and intent.

Because it is watercolour Namatjira work leans on some of the same techniques used by Heysen. Neither is at all experimental in their medium. It is clear that the success of each of them betokens a hunger for landscape art in Australia, art about the land that can cross cultures and is about observation, belonging and place.

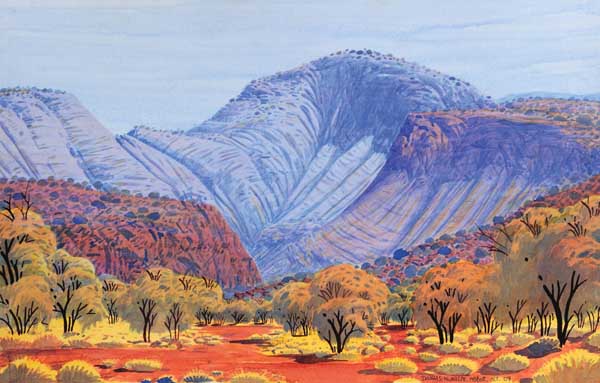

The first thought of an exhibition of paintings from Hermannsburg artists is of a series of almost identical works endlessly recycling the same views, the same shorthand for trees, the same purple and blue distant ranges and various renditions of the peculiar way the Central Australian mountain ranges flow up and are capped by rocks. Yet close slow careful attention to the works on show reveals many variations on this theme, bright stained glass window effects by Mervyn Rubuntja, very pale very detailed effects by Hubert Pareroultja, childlike simplicity by Gwenda Namatjira and angular forms by Kevin Namatjira. And thus the exhibition becomes a place of richness, of fascination, of comparison and discovery, of echoes as the exhibition title has it.

There are more variations to describe but I would like to use this space to suggest such close attention can also find value in typical paintings displayed in a Rotary art show or similar amateur venue. This is not a flippant or disparaging comment. I would suggest that the same passion that makes Aboriginal people paint their country, their surroundings again and again in the style they have inherited from Albert who learnt it from Rex Battarbee who was imitating Hans Heysen is like the passion of the non-Aboriginal painters who paint landscapes again and again in borrowed and inherited methods. Neither really experiments with their medium though each expresses individuality in their approaches. Each paints with ritualistic repetition that suggests that it is the act of painting that involves as much meaning and satisfaction as the result. It is an approach that thrives not on novelty or development but constant reassertion of connection and tradition, in a sense - manifest belonging. The fact that quite a few Central Australian artists paint both Hermannsburg and dot painting style shows up their artmaking as not about creativity as individual invention (often given precedence in many Western histories of art) but about creativity as homage and profound connection to the past.

Beyond and within such art movements are occasional works that stand out because they do demonstrate the artist forgetting their careful models and making something new and fresh. This is what happened when Emily Kngwarreye let go of trying to be precise in her batik and then in her paintings. It is what we see in some of the paintings made by Billy Benn at a different art centre the Mwerre Anthurre Artists (set up in 2000) in Alice Springs. (‘Mwerre Anthurre’ means ‘beautiful art’ and art made ‘proper way’ in the Arrernte language of Central Australia.) Billy Benn’s acclaimed work (a book on it is about to be published by IAD Press) has been described by former deputy director of the National Gallery of Victoria Frances Lindsay “as a trajectory of [the] Albert Namatjira [style].” Indeed so is Otto Pareroultja’s tiny speculative and exploratory 1940 work “Mount Hermannsburg” shown in “Echoes in the landscape”.

The Ngurratjuta Iltja Ntjarra ‘Many Hands’ Art Centre was set up in 2003 following the anniversary of Albert’s death in 2002. It was set up to help the tradition he started both continue and flourish.