Just as there are two ways to approach David Walsh's Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) - by ferry to the front or by road to the back – so there are several ways to approach his collection. You can engage with the general theme of "sex and death", a descriptor which the museum staff did some back-peddling on at the media launch but which gives a pretty fair summation of the curatorial road most travelled in this underground labyrinth – from the remains of a suicide bomber fashioned in chocolate by Stephen J. Shanabrook to a frieze of 150 plaster-cast vaginas by Greg Taylor skirting the length of one wall, and what must be the only on-site cemetery in a museum. You can have your ashes interred here in a wall of death, and Walsh’s own father was the first casket off the rank, as he proudly showed us, pulling back the red curtain like the final act in the Wizard of Oz. Or you can focus in on individual works, shutting out the rest – Anselm Kiefer’s “library” of lead and glass books, Sidney Nolan’s massive “Snake”, Erwin Wurm’s altered Porsche “Fat Car”, Christian Boltanski’s installation as autobiography, Brigitta Ozolins’ numerical maze, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s neo-expressionist graffiti, or Chris Ofili’s “Holy Virgin Mary” which gave Mayor Rudy Giuliano conniptions when it was shown as part of the “Sensation” show in Brooklyn – the very show that Brian Kennedy thought would be too hot for the good burghers of Canberra. A third way, and perhaps the best, is to view the whole site as an installation with David Walsh as the conductor and his hand-picked orchestra made up of the artists, architects, curators and service staff for vineyard, brewery, restaurants, and accommodation that he, and his gambling money, has brought together. There are a few bum notes along the way, and not everything is always in tune, but like listening to Wittgenstein’s one-armed brother playing the grand piano it is an experience you will never forget.

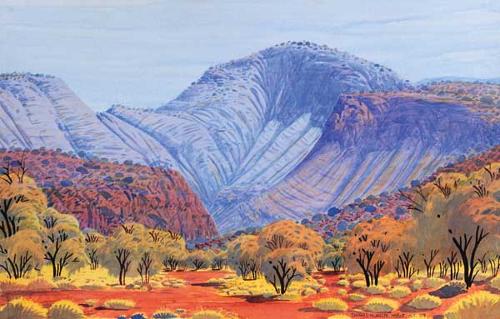

Imagine a building considerably larger than the MCA in Sydney, buried underground and surrounded by vineyards, glorious scenery, and – for the opening weekend at least – rock and jazz bands on two stages front and back.

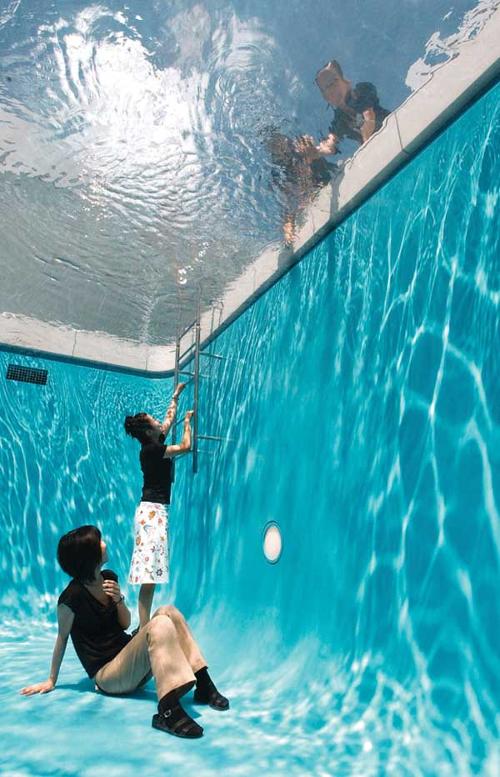

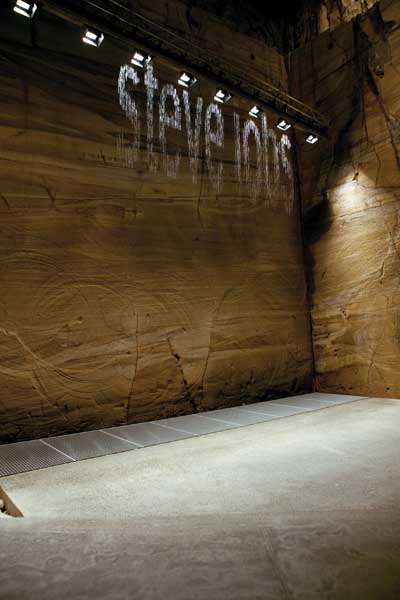

A sheer cliff, one of the most astonishing elements of the overall “installation” has been excavated downwards. At its base a long corridor has a bar at one end and an internal-waterfall-as-artwork at the other. This is by Julius Popp and is called “bit.fall”. As the water cascades downwards computer-generated words form within it. Water on water, like Ad Reinhardt’s black cruciforms on black canvas. You have to really look to see it. Then you enter the maze of galleries and, over many hours, work your way back up to the surface. You see a block of ice frozen from black ink, slowly melt across the gallery floor, and you realise that many of these works are about process as much as they are about “sex and death”. The digestive process is one such sub-theme. If you know which toilet cubicle to enter in the unisex toilets behind the absinthe bar you can be the centerpiece of Austrian art team Gelatin's installation of mirrors, video monitors and binoculars-on-a-string which allows you to watch yourself having a crap. Upstairs, if you go at the appointed hour, you can watch Belgian artist Wim Delvoye’s “Cloaca Professional” being fed, or, at a later hour, excreting. There is a “feeding time at the zoo” urgency to some of these works. You had to be in the right place at the right time to witness Roman Signer’s staged car crash on the opening night, producing a work that will remain as a “paralysed” sculpture. You had to know where to look to find the thirty Madonna fans in a sound-proofed room sing a cappella versions of her “Immaculate Collection” album, or where to find the secret door to hear the two women engaged in telephone sex (clue: look for the red fire extinguisher and push against the wall).

Like Nolan’s “Snake” you move in serpentine curves from the sublime to the ridiculous, from the gut-wrenching to the chilling. As you take the tunnel down to Anselm Kiefer’s library you are invited to make rubbings on blocks of stone brought from Hiroshima. The results of your participation are photographed digitally and scanned onto the internet.

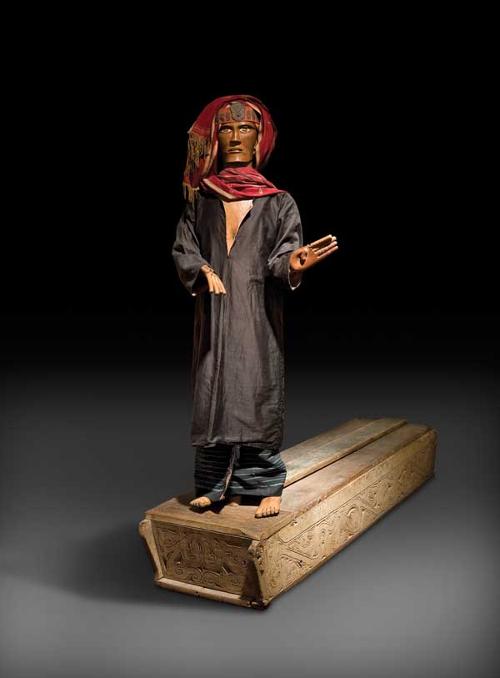

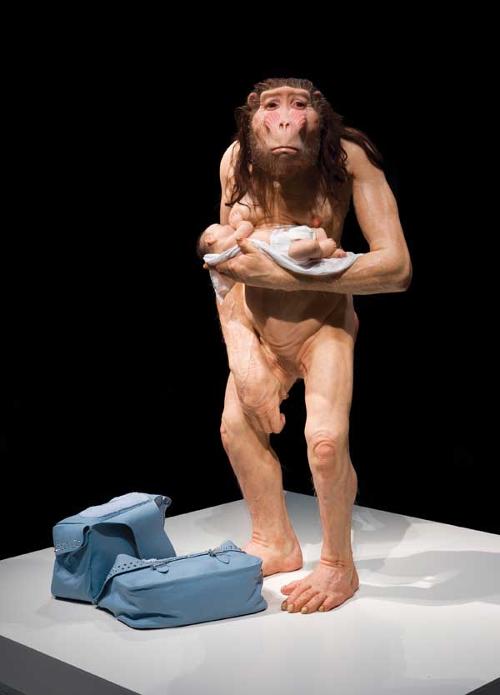

A large couch looks welcoming, as your legs are growing tired, until you realise it is part of a euthanasia installation by artist Greg Taylor and Australian euthanasia campaigner Philip Nitschke. So you stagger on and start to become critical of some of the hang. You like the Egyptian mummies that loom like Easter Island statues out of the submarine darkness of some galleries, but you wonder if this is the right setting and lighting for the slowly turning Damien Hirst Spin painting. You are also deeply disappointed in the bordello-red curtains against which the huge Jenny Saville trans-gender painting is hung. All the colour is sucked out of it through this unnecessary visual feedback. And then you are uplifted, often by the homegrown Australian work. It’s good to see James Angus’s “Truck Corridor” again, and Callum Morton’s “Babylonia” is like a weird stage prop for a Coen brothers’ movie.

And up in the shop, as you flick through the phone-book-sized catalogue you realise there is so much more in this collection that is not yet on display, including paintings by Peter Booth and Brett Whiteley. The architects are still working on a roof-top enclosure for Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s astonishing installation of zebra finches playing Les Paul electric guitars. And some of the work is off-site, most notably “In Silence” by Chiharu Shiota at Detached museum, curated by Olivier Varenne. A grand piano was burnt on the street outside this former church and its charred remains are part of the installation inside.

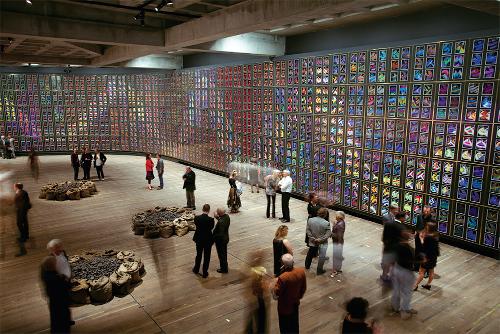

And you never know when you have seen everything, or who has seen you. Apparently David Walsh has his own living accommodation high above the Sidney Nolan gallery with its 1,620 individual panels that snake around a huge meat grid by Jannis Kounellis. Walsh has built a secret viewing window into his floor, and can watch you watching his “adult Disneyworld”.

Peter Hill