The craft of silhouette-making has been around since the 18th century and in that time silhouettes have served many purposes - from rendering a realistic representation of the human profile pre photography, to being used, in conjunction with the pseudo science of physiognomy, to decipher character traits like intellect and sincerity. The craft of making silhouettes has regained popularity and is still in use today. In Chinatown in Sydney there is a man who can cut out your silhouette from black card in one whole minute for the tidy sum of two dollars. He manages to cut out single wisps of hair and voids for personal objects, such as eyeglasses, all in the time it takes for you to rustle inside your bag for the two dollars. It's a novelty act, one where your nose is slightly off and your forehead exaggerated. Kate Scardifield is an artist who uses the art of silhouettes to create narratives. Her artworks are comprised of fragments and layers. Each layer in her staged, silhouetted worlds have been cut out from fabric, paper, and wood and brought together to create silent vignettes that perform along the gallery wall.

On first encountering Scardifield’s life-sized all female silhouettes you feel like you are watching a pantomime being enacted from the pages of a 19th century Hans Christian Andersen story book. The beautiful brocaded fabric and whimsical characters seem to dance along the walls. It isn’t until closer inspection of the individual pieces that you realise the playful atmosphere is underscored by a layer of macabre drama. One where a female silhouette is wielding a knife held high ready to attack and another is pointing accusingly at an unsuspecting victim.

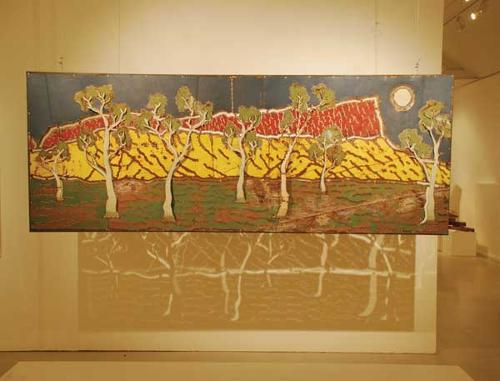

Performance is an important layer in this work as the artist transforms the gallery into a theatre of sorts. There is the staged theatre of drama and action of the figures juxtaposed with the operating theatre where the artist cuts out the silhouettes and into the body. Exposing what lies underneath is at the core of Scardifield’s work as she peels back the layers to show what is usually hidden from view. The inner organs and vascular systems of the body are rendered from delicate fabrics reminiscent of the colour of blood vessels. The cage-like crinoline, used to secretly restrict and exaggerate the natural female silhouette, is also revealed. The interior silhouettes of bodily organs have been flattened and arranged into their own decorative patterns. They carefully balance on top of each other and resemble the contours and topography of a landscape.

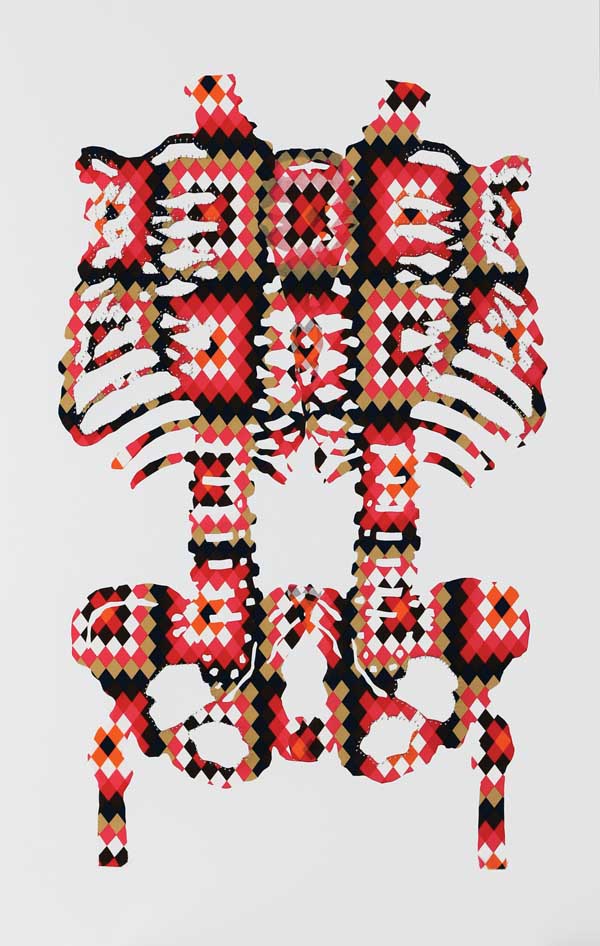

There’s also an old world element to the work. The dresses, the hairstyles, the craft of silhouettes all herald a time long ago, when there was a distinct divide between the sexes. These elements of the past function perfectly as the backdrop for the traditional domestic crafts such as dressmaking and decoration, which were usually women’s work. They are placed side by side with the male world of science. Returning to the operating theatre and the sciences of physiognomy and psychoanalysis, the artist has tapped into these male worlds. She has emulated the Rorschach inkblots, traditionally used for the psychological interpretation of a person’s personality, in the representation of the inner organs.

Scardifield has layered piece upon piece to create the whole tableau. She is simultaneously peeling them away to reveal a deeper story underneath. Just as an audience member at a play is left to take what they want from a two hour performance, the viewer of these narratives is left to create their own story from the many layers and elements given to them, using the individual pieces or indeed the sum of them.