The official opening of MONA was heady. It was not, as you might have imagined, a star-studded christening and nor did it comprise a full complement of politicians and dignitaries. There was an absence of pomp and profuse jubilation. Largely, the throng seemed to consist of Tasmanian artsworkers, passionate patrons of the arts, local artists and a few from interstate and abroad. I have never seen, let alone consumed, such quantities of black caviar - slipped down with Grey Goose shots (highly commended by this reviewer). For the locals it was a singular privilege to be there: the advent of MONA radically changes our lives for the good. Though it has been a prominent thought in many people's minds, the fact that Hobart is now home to the largest private collection in the southern hemisphere takes a bit of swallowing. Even with the rows of shot glasses, filled and refilled with vodka and absinthe, the most intoxicating and exorbitant aspects of the event were the art and architecture.

Like the party itself, the entire MONA phenomenon is hip in a way that is a little bit goth, a little bit country and a little bit rock n’ roll. That is to say, it’s perverse and as coarse and vulgar as it is refined and elevating. Berriedale lies behind the flannelette curtain. The site of what is now MONA is a beautiful peninsula that was quarried in the early days of European settlement and established as the Moorilla Estate winery in the 1950s. Today, working class suburbs, factories and machineyards flank the bucolic slopes of the vineyards. Over the main road, directly opposite MONA, the Granada Tavern advertises 'parmas’ for twelve dollars on Wednesdays (no recommendation: I haven’t been there for decades). It’s arguably a museum itself: a memorial to 1980s pub rock and beer brawls. Who would have thought, sweating profusely to the Kevin Borich Express or Chain at the Granada, circa 1980, in years to come there would be a ruddy great Anselm Kiefer within a kilometre radius (it’s "Sternenfall" 1999). Any incongruity between such striking and muscular expressions of excess is illusory. Indeed, just such category slippage seems to be David Walsh’s stock in trade.

The very best parties create a slipstream unpunctuated by formal introductions, in which it becomes possible to converse instantaneously with strangers, and thus I found myself in raptures over a selection of cheeses, sharing my enthusiasm with the young IT crew responsible for the MONA iPod gadgetry. Visitors can navigate the museum by receiving information electronically, and send records of their visit to their email addresses. It’s a system I imagine many museums and galleries in the world will adopt, for its information and communication capacity, and because it makes no incursion into exhibition design. The folk who’d worked on it were tired and self-effacing, saying that there was more tweaking to be done (my experience of the device is that in its teething period, it’s already working well).

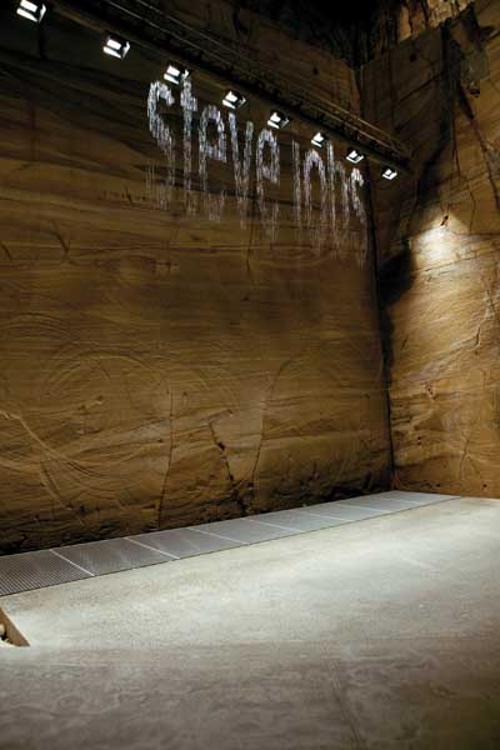

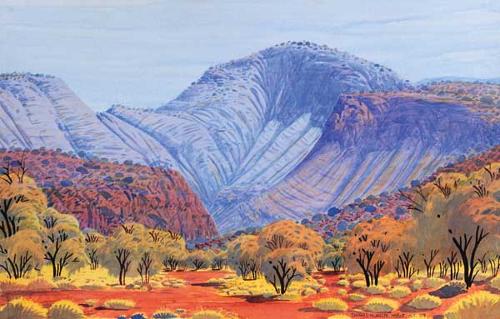

From MONA the views beyond Berriedale are striking. Mt. Wellington looms at an interesting angle and there is the charming vista of the Derwent and the rolling mountains to the east, which can be surveyed from the Museum’s (highly commended) café. Approaching by ferry (also strongly recommended), one passes the zinc works at Lutana, frighteningly beautiful in its own evil way: the corroding colossus spews forth plumes of smoke, day and night. The architecture of MONA couldn’t hope to compete with such brutal majesty, but it pays tribute. From the river, the Museum’s exterior – rust-coated Corten steel and waffle-grid concrete, sounds an echo to the monster. Not that there is a great deal to be seen from the outside. Designed by Nonda Katsalidis, the internal space was created by excavating the sandstone cliffs. Entry into MONA is a descent into Hades.

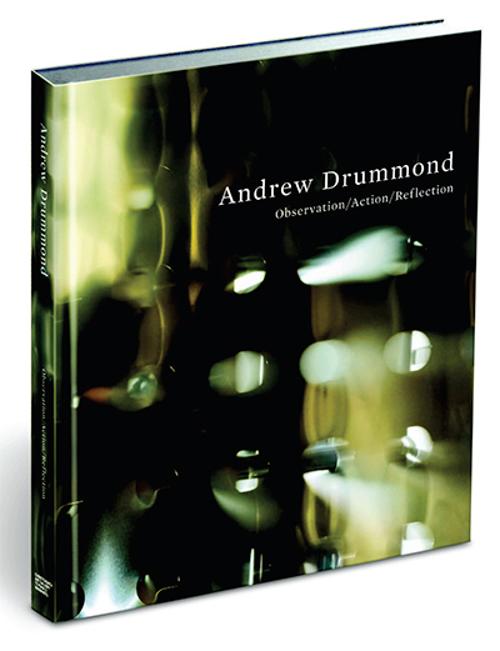

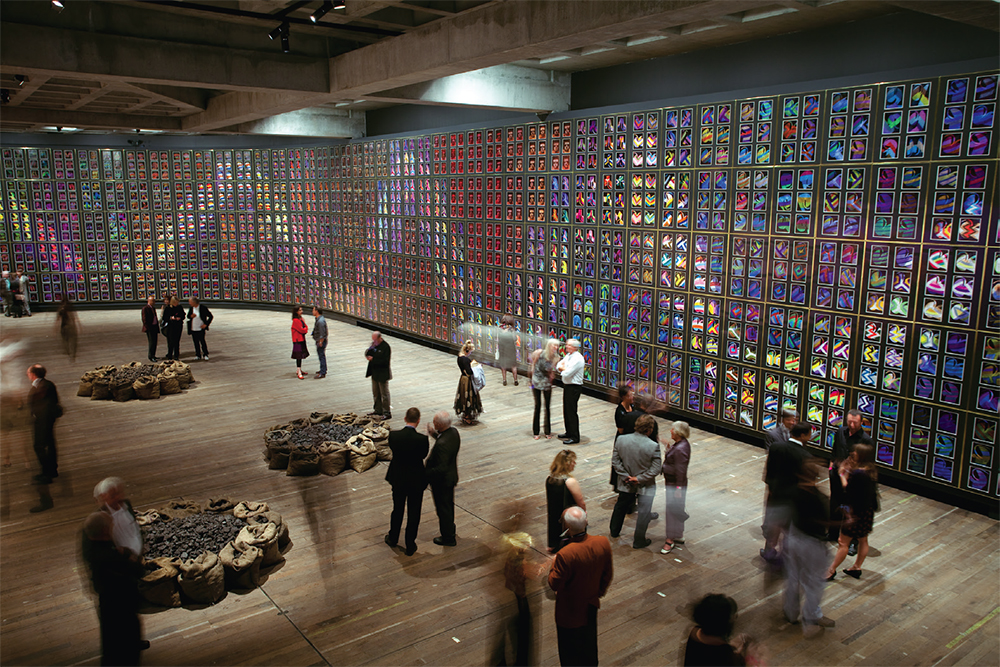

The spellbinding underworld resembles an enormous nightclub more than a traditional museum. The cavernous space is hospitable: it’s opulent, alluring and licentious – not simply because there happens to be a bar near to where the lift stops on the lowest level (high praise for the gin, elderflower and rosemary martini). Sheer exposed sandstone lines the lift shaft and walls of the approach. The architecture and the exhibition design define and dramatise the tenets of this inaugural exhibition, and presumably the themes of the collection as a whole. The structure is quite disorienting, and this and other topics are whimsically elaborated by David Walsh and others’ writings in the catalogue, “Monanisms” (and elsewhere). The underground chambers certainly contrive to create a terrain for questioning, doubt and instability. More than that though, MONA is a redemptive and revivifying place.

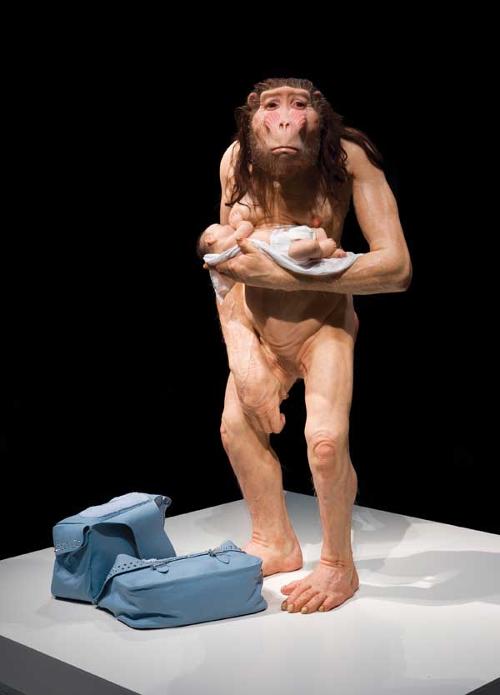

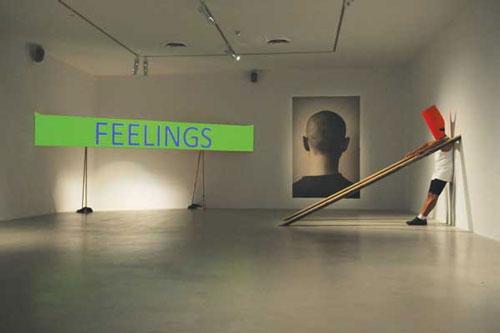

The lighting is masterful. Optic fibre lighting allows objects to twinkle out of the dark, and the display cases cast luminous pools onto the polished concrete floors. Amongst numerous antiquities on display there is a starburst configuration of Roman coins, twinkling in their cabinet, their details picked out in light and shadow. Most of the modern and contemporary works are selectively lit in much the same way. Sidney Nolan’s enormous “Snake” (1970–72), hung on a purpose-built curved wall is breathtaking. A good number of the objects in “Snake’s” proximity, and indeed throughout the Museum, are grotesques. Numerous contemporary works depict cruelty, perversion and the darkest aspects of human love. The themes are Sadean.

MONA summons the Marquis, who provides some keys to the dungeon, including the apparent paradox whereby civic virtue has sprung from decadence. It’s nothing other than poetic, surely, that the Museum is the brainchild of a gambler, whose black gold offers the public the opportunity to dream, to retreat, to become lost, and to feel enlarged and invigorated. Imagination needs to retreat from society: it needs to escape from the constriction of civilised or civic values, but such an escape is seldom possible. It’s a sad irony and point of frustration that publicly funded institutions, responsive to taxpayers and bureaucratic benchmarks, can seldom permit the sort of rent in the social fabric that allows for expansive public discourse and engagement. What can so easily get lost in the public domain is precisely “human desire”. MONA invites us to be libertines, to plumb the depths of human experience, and to cavort with chance.