It is an occasional exhibition that dares provoke the status quo, realigning what we thought we knew of the world, indeed shaking us out of our malaise. Tania Ferrier's "The Quod Project" is one such show. Based on the brutal treatment and internment of Aboriginal people on Rottnest Island (or Wadjemup as it is referred to by Noongar people) and equally importantly in this case, the subsequent convenient ignoring of such a history, “The Quod Project” brings to light the continuing 'problem' Australia seemingly has of dealing with its colonial past.

So often, perhaps due to a contemporary culture of over-museumification, there is a contemporary idealisation of sites that for one reason or another have a sordid attachment to our past. Rottnest Island, directly off the coast of Fremantle, has long been a favorite local holiday jaunt for locals, and it has deliberately kept a low key, minimal impact aesthetic to its accommodation and tourism-based activity. However at times this attachment to previous heritage has leaned toward a congenial atmosphere of place at the expense of cultural history.

The old camping grounds, now a marked burial ground and The Quod are two such examples. Now a comfortable resort, those who stay at the former prison are not told the history of The Quod where an estimated 373 Aboriginal men died during the island’s years as a “colonial concentration camp” (1838 to 1931). Ferrier’s prosecutorial tone does not hold back in this damning exhibition which I think importantly utilises the aesthetic of both gallery and museum display, intelligently configuring a layout that pays homage to the history of the museum and its power to own narrative while also acknowledging that visual art still holds a powerful position in broaching politics. Indeed the exhibition can be read in line with the recent resurgence of the body politic and the role of open information in the commons as positioned by Jacques Rancière, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri but that would be oversimplifying what is the outcome of a long and personal journey by the artist.

Co-telling the intertwining story of her own deeply affecting family story with that of the Aboriginal community imparts a responsibility onto all those who view this exhibition. As Ferrier examines her own attachment to the island so too are we drawn along on a tour of our own memory and failure to acknowledge, to avoid the truth and to partake in a peculiar homage to our own comfort at the cost of understanding. It’s crucial stuff and reminds us of the constant role history plays in our own sometimes alarmingly passive view of the present. Quid pro quo - if it has happened, we will react to it; Ferrier’s hope is that the balance of things is at least based on the truth.

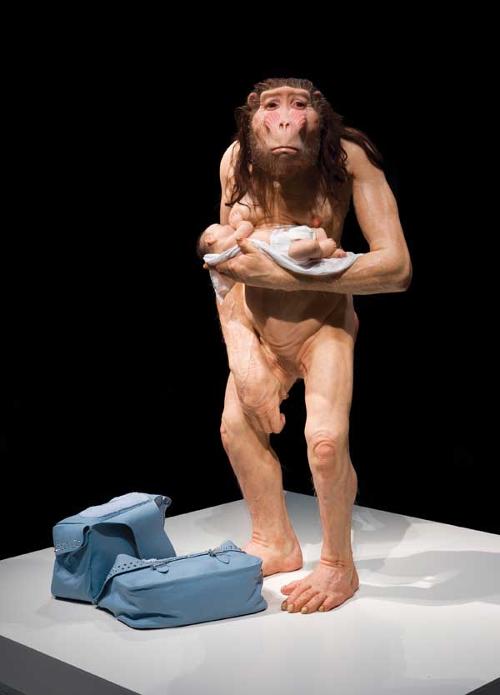

Encompassing only slightly tongue-in-cheek reassemblages of past Rottnest Island imagery, hard-hitting and shamanic video with narrative from Aboriginal elders Noel Nannup and Cedric Jacobs, photographic portraiture in collaboration with James Kerr, family photos, a floor map and a dark and beautifully made life-size model of the cells used, “The Quod Project” is not for the faint-hearted. Indeed at times it is almost apologetic due to the nature of its subject matter. Working respectfully with and alongside local representatives of the Aboriginal community adds research quality and depth to a show that, although by no means the first to broach the subject, picks up the history of Rottnest Island at a crucial time. At times perhaps too literal, Ferrier’s “The Quod Project” is nonetheless a reminder to those considering the future development of the island that “history is alive in the walls of The Quod”. We can only hope that this installation finds a permanent home on the island so those enjoying the wonderful breezy ambience of Rottnest can also acknowledge and appreciate the cruelty of its past in the hope of a better future. The past is not just built on pleasant memories - a world built on the acceptance of preferred memories is, as we know from the literature of Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, a depthless existence if not a lie.