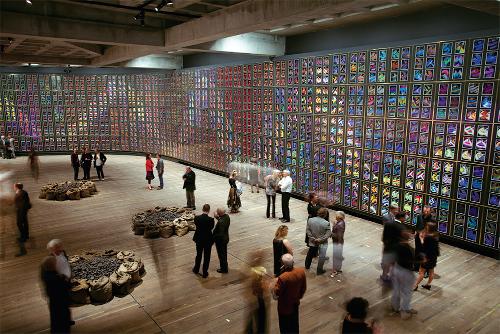

It is most appropriate the National Gallery of Australia staged an exhibition of such international significance as "Life, death and magic". The exhibition, accompanied with a lavishly illustrated catalogue publication, presented the animist art of Southeast Asia, extending as far north as Taiwan and southern China, and featured a dazzling array of objects including sculptures, metalwork and textiles. The National Gallery is home to one of the most important repositories of Southeast Asian textiles in existence today and it is Australia's geographic proximity to our northern neighbours that makes Canberra such a fitting location for the priceless collection. The National Gallery’s Senior Curator of Asian art, Robyn Maxwell, included a number of the finest examples, as well as loans from Southeast Asian, European, United States and Australian art museums, in “Life, death and magic”.

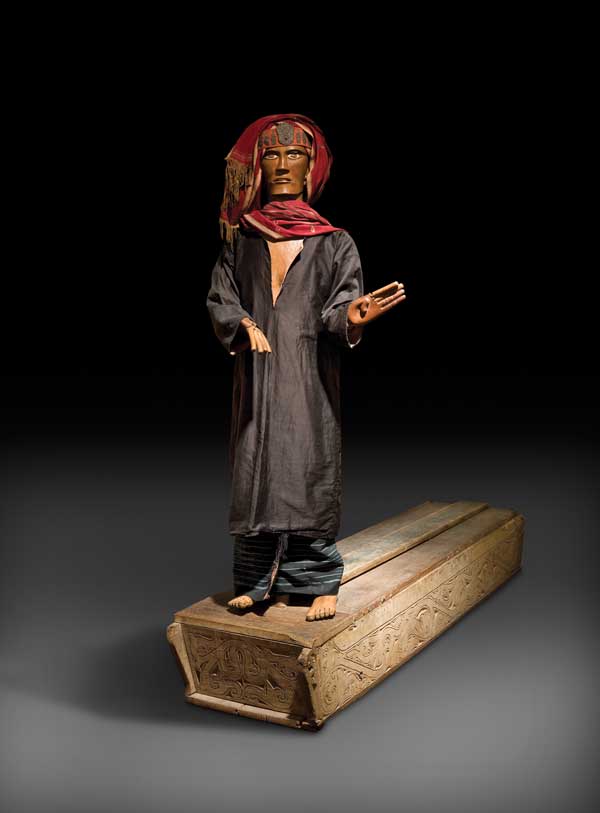

Few Australians have an awareness of historical art traditions just north across the Timor Sea despite the increasing multiculturalism of antipodean society since 1994 when the Indonesian writer Ratih Hardjono ironically described Australia as the 'white tribe of Asia’. This is surprising considering the profound resonance existing between the archipelago’s indigenous spiritual systems and those of Aboriginal Australia. Stone and wooden sculptures of ancestral couples from Indonesia’s outer islands, displayed in “Life, death and magic”, evoke a parallel universe where tribal lineages were born through the union of archetypal male and female beings at the beginning of time. As in Aboriginal society, fertility was everything and images of generation and regeneration pervaded the National Gallery’s exhibition. A Sumatran life-size “si gale gale” mortuary puppet, intended as a ‘child substitute’ for a person who died without offspring, was made with articulated limbs to dance at the funeral rites. Its concealed wooden phallus is provided with a pulley to humorously imitate the movement of an erection beneath the robes.

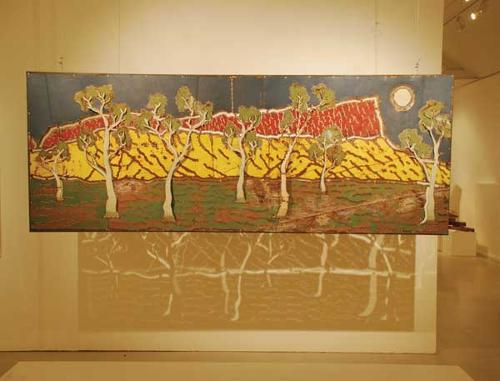

Depictions of boats on heirloom bronze kettledrums made in north Vietnam, nineteenth century Kalimantan mortuary panels or the famous ritual ‘ship cloths’ of South Sumatra alluded to ancestral journeys through the waters of the archipelago. It is a timeless narrative whose elements echo the ancestors’ travels that created the Dreaming song-lines criss-crossing the landlocked Australian continent. The striking visual eloquence of Southeast Asian art was palpable in these works of art though the stories, once preserved in oral tradition, which held the key to their meanings have all now been almost completely forgotten. Many of the exhibition items were once family heirlooms that have been subsequently preserved in museum collections, following their owners’ abandonment of animist beliefs and conversion to the introduced faiths of Islam and Christianity, an act often perceived as an assertion of modernity. Nevertheless, reptilian motifs decorating a Tetum woman’s ceremonial skirt from West Timor were a reminder of the implicit connection between ancestral beings and the earth that is common to the indigenous religions of both Southeast Asia and Australia. Ancient Timorese belief regarded the island as the magically transformed body of a crocodile that once swam from Makassar across the ocean to the place of the rising sun.

The magnificent beauty of over two hundred and fifty works of art included in “Life, death and magic” easily lulled the viewer into forgetfulness that Southeast Asian tribal societies once widely propagated headhunting cults. Putting aside the macabre notion that the ritual removal of enemy heads ensures fertility, walking through the National Gallery’s exhibition I found myself involuntarily remembering what a West Timorese weaver said to me many years ago, “Adatnya berat” meaning: customary law, with all its social obligations, is heavy duty. As Maxwell observes in the catalogue, many of the finely-crafted works of art were created for life cycle ceremonies whose enactment hinged on family status and the inevitable ritual duties obligatory for each generation.

The recurring totemic motifs of animals, birds or plants, appearing in the exhibition in concert with images of woman and man, whether the benign mother or living corpse, stand in diametrical opposition to the spiritual values implicit in the art of the religions of The Book - Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Western society's systematic dismantling of kinship relationships over recent centuries is yet to be tested by history as creating a viable alternative to the complex clan networks that bonded indigenous cultures. Belief in the power of the ancestors, immanently present in the cycle of life and in death, inspired the core of Southeast Asia’s aesthetic heritage. Here the observation regarding family relationships by the Australian author Patrick White is very true: "...blood is the river which cannot be crossed."