When artists start reflecting on life and their own mortality, the humble viewer can usually be guaranteed of a fairly morbid time. This was not so with Life is Getting Longer which, by dint of its fresh approach to an unwieldy premise, diverted viewer expectations down a much sunnier route.

At stake here were concerns about old age, encroaching frailty and decay, and an intently critical and frequently unflattering interrogation of the 'self', as understood through visual and psychological study. Ascribing tenuously to the conditions of portraiture while defying all preconceptions of that overwrought canon, the exhibition was lent a further twist with the application of time, as an ingredient as active as the physical materials. All but one of these artists participated in the 2004 exhibition Life is Very Long. Rendall's approach of retaining this line-up reaps fascinating results - their progress in time as well as space can be measured.

Nick Devlin's assemblage of found and stacked television sets projected a fragmented transmission of the viewer, courtesy of the CCTV cameras lurking secretively in the crevices. Holding a mirror up to our failings, Devlin forced viewers to consider themselves as broken up body parts, moving self-consciously within frames normally associated with escapism. Jon Jones similarly presented beautifully realised celebrity portraits copied from the pages of glossy magazines, interspersed with self-portraits. The domestic size canvases, while endearingly in awe of their subjects, imbue them with humility - enfeebled and prone.

Speculative self-critique was invited by Justine Khamara through the study of her biological provenance - namely, her mother and father. Their heads were obsessively cut from hundreds of photographs and montaged in a circular, wall-enveloping installation. Their bulging eyes stare out in helpless repetition - seemingly unsure as to the motives of their daughter, rendering the work palpably sinister. On the opposite wall Eleanor Crook presented the most singularly startling piece in the show - a wax likeness of a deceased and decayed woman. In this horrific invocation of human mortality, long, wiry black hair, sunken eyeballs and pallid skin combined to engender a visceral repulsion, all the while inviting closer inspection.

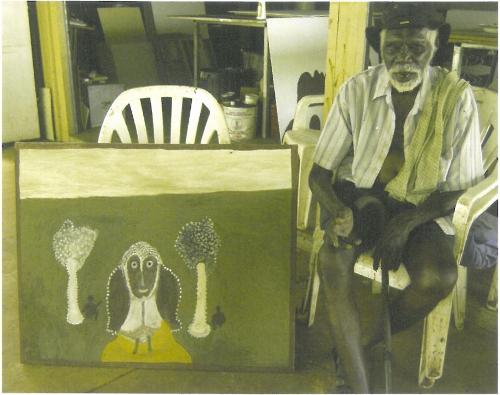

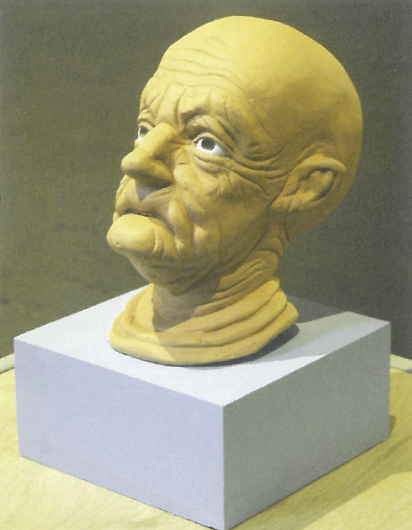

Steven Rendall's own painted constructions, if not as graphically confrontational, were at least as psychologically unsettling. His 'portraits' straddled the line between abstract and figuration, exploiting an ill-definition that dwells between with relish. Garish colours and thick, impasto paint took hold of their canvas boards with imputative disregard for the conventions of painting. While individually disparate and preoccupied with their own concerns, each of the works bled into one another spatially, to create a dense visual environment permeated by a meandering pathos. Michael Bullock's decrepit sculptural projection of himself as a thirty-seven year old woman possessed the space admirably. His fidgety handling of the clay and his shoddy workmanship practices befitted this evocation of his self-decay.

The slightly rambling nature of the exhibition, reinforced by the oblique catalogue introduction penned by Rendall, belied the conviction and consideration with which the show was wrought. The free-form approach adopted by both the curator and the artists rendered disarming and approachable such themes that might, in other hands, have become morbid and impenetrable. The gentle naivety of Life is Getting Longer was merely the blanket in which resided sophisticated and deeply considered accounts of the difficult questions it posed.