When Frank McBride first heard of the Miss Australia: A Nations' Quest touring exhibition from the National Museum of Australia, premiering at the Museum of Brisbane from early October, the concept for a sibling show began to gestate in his mind. What he curated was A Man's World, a mixed bag of concepts about how men define themselves today and the changing face of masculinity.

What is immediately apparent when entering the Museum is the cohesion of McBride's selection. Fourteen artists are represented, each focusing on differing concepts and the breaking down of stereotypes. Mention is made briefly in the didactic wall panel of the feminist movement, but besides this the exhibition shies away from stipulating any clear pro-masculine concepts. In fact what comes across is a rarely seen delicacy in relation to masculinity.

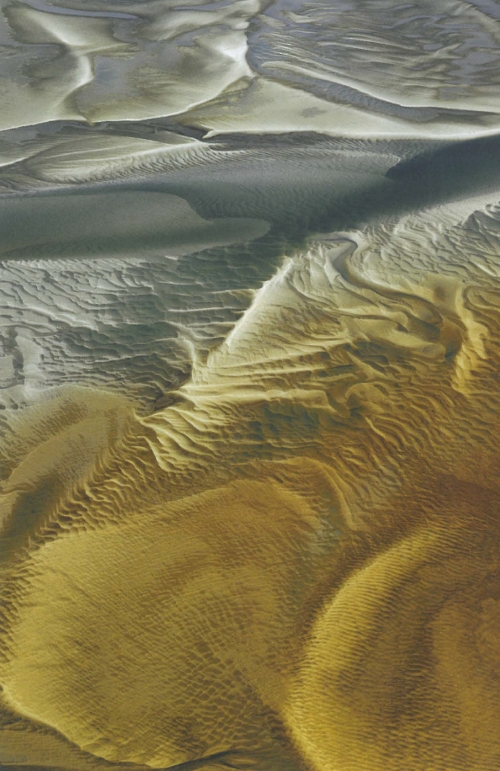

This sense of fragility can be seen in works such as those by Andrew Curtis, a Melbourne-based photographer, who lights and shoots various construction components at night. In Triholm Avenue (2001), a typical slab takes on almost religious proportions, its inner light seeping across the ground it rests on. In Toorak Road 2 (2002), he lights a monolith-like shape from behind, the masculine figure now independent, yet hidden within shadow. To Curtis, the site of construction is a definitive representation of masculine thought and creation. The sharp, clean lines dictate no nonsense, straight to the point imaginations. A construction site, in Curtis' mind at least, is a place of both rigid practice and a surprising element of expression.

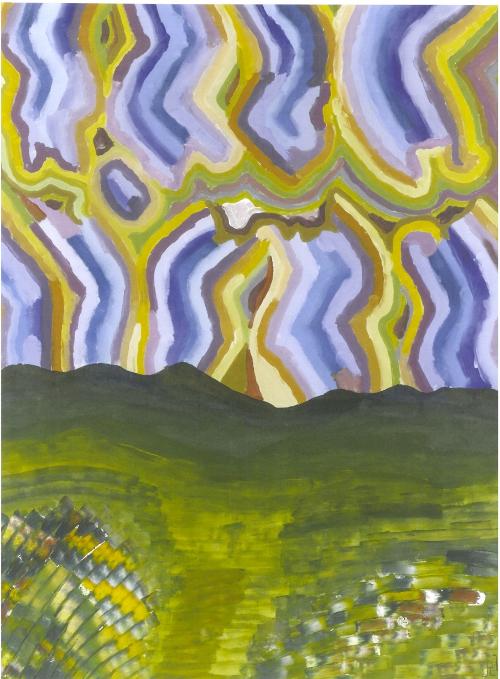

Dani Marti, another artist from Melbourne, further continues an expression of masculine tenderness within his delicately woven pieces. The artist utilises polyester, manila rope and rubber to stitch distinctly different artworks. The relationship between father and son holds importance for certain artists within A Man's World (2002). Euan McLeod, in Rain man, depicts the ethereal presence of the father, a figure-shaped storm appears to dump its misery upon the lone son.

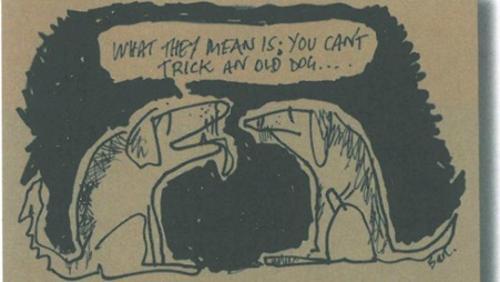

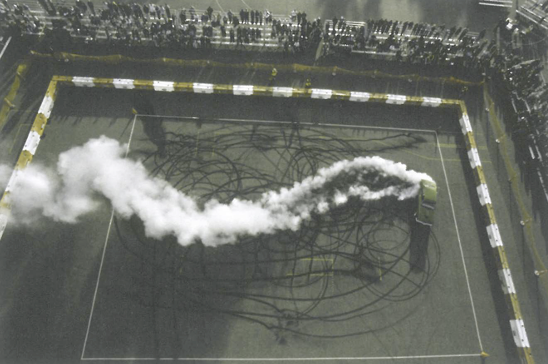

Though McBride stated a desire to approach the masculine from differing directions, it appears that the concept of the 'larrikin' is unavoidable. In Ben Morieson's series of works, shot on location at Burnout 2004, a site of extreme larrikinism for sure, the artist shot progressive images of cars from a cherry-picker as they screech around a cordoned-off area. The vehicles streak rubber across clean tarmac to create some type of vicious Jackson Pollock if he was inclined to take a spin on Mount Panorama. Strangely enough the Torana isn't exactly a precise tool for art, but the experiment is an amusing one at least, if a little puerile.

A different, yet informative, choice within the exhibition was to get the artists themselves to write a small paragraph attached to the labels, stating what the works mean to them. In the case of A Man's World, the artist statement seems to work relatively in favour of the exhibition. However it comes unstuck with the work of Adam Cullen who paints the portraits of the killers of Anita Cobby in slathering strokes of acrylic. The artist then succeeds in shooting himself in the foot when he makes strangely prominent use of his limited word count in highlighting why he does not condone the killings, he does not sympathise with the men nor wish to martyrise them. In context perhaps a small mention of this is appropriate, but the artist appears afraid of his subject. There is little point in crafting something controversial when you need to qualify it with words.

A Man's World is an exhibition that keeps an open mind on the subject of contemporary masculinity. The artists benefit from a fairly light-handed and sensitive curatorial approach, in the end giving room for the viewer to appreciate the enigma that is the modern man.