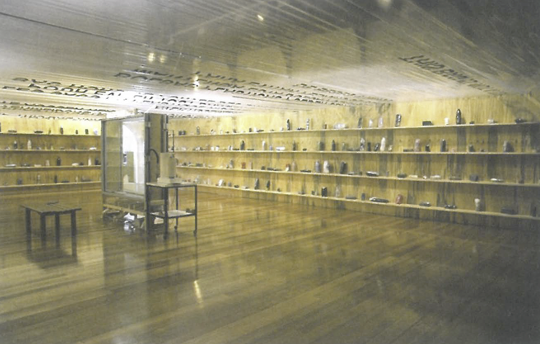

On entering the space there is nothing of the usual sweet elegance of the Devonport Regional Gallery, but instead functional plywood-lined warehouse meets minimalist Japanese department store display. Objects are arranged on shelves which line the walls. Each of the objects is gift-wrapped and vacuum-packed and beneath these layers are simply used containers. The objects are evenly spaced with labels indicating a belonging to real people living in Devonport. I know this because I recognise some of the names. Whose containers are they? Have the people provided them? Are they from the artists' recycling bin? Is it lost property waiting to be reclaimed from this constructed dispatch room? Does it matter? It clutters up the same world we all live in.

Other objects are also in the room. A glass cabinet seems to breathe, sucking small circles of paper cut from telephone directories into the air and onto a vent before clogging up, shutting down and starting all over again. In a video work the sound of laboured breathing accompanies an arm enclosed in a plastic bag and a series of individuals are invited to breathe into the bag through an attached drinking straw. There are no edits in the footage. The same straw is breathed into by one person after another. I am relieved to read the title, Family First, and indeed have already become conscious that only people who loved and trusted each other would participate in such a disgusting event. As that thought is articulated however I realise that we all do much the same thing all the time; we breathe in the air of complete strangers. Irrespective of who we are and what we have done, we inevitably share everything. There is no 'away' that our money or position can buy. Then I recall the work which I had overlooked on entering the space, a video loop of canaries in cages. There is no escape. We all rely on the same vital elements. Perhaps we had better decide to put the best quality ingredients into the mix rather than wait in deliberate or blissful oblivion until it is too late.

Recycled air and waste tie the works in this exhibition together. Heaps of 'rubbish art' has been made over time to the extent that it was given the label 'Rubbish Theory' by Michael Thompson in 1979. Gustav Metzger's conceptual piece Integral Part, a bag of rubbish at the Tate Gallery in London in 2004, a remake of a work the artist had exhibited in 1960, was accidentally thrown away by a cleaner. Then there is Joseph Beuys' historico-political work in which he and a couple of his students swept up the rubbish after the May Day military parade in Karl-Marx-Platz in East Berlin in 1972. In 2001 British artist Ceal Floyer won the prestigious Paul Hamlyn Foundation award for her black plastic rubbish bag of art gallery air entitled Rubbish Bag which is a critique of the mystery of art. These examples are just a few of many.

Vella's work is rubbish art with complex purpose. It is simultaneously personal, political, relational, humorous and generous. To me it is this generosity which places the work within a relational frame. It invites the viewer to participate in its construction. In fact the building of the relationship between the players is central to the work. Mr Lumb of Olive Court Devonport brought this home to me. Dressed smartly in his grey suit and tie, this mid-60s public servant and gentleman began checking the addresses for names he knew. He was bemused at what they would make of the artwork they were to receive and wasn't sure at all what he would do if he found his name. At the same time he recognised the significance of the global issues needing to be confronted. After a while I saw him charging across the room with determination. Yes, there was an object addressed to him. In the joy on his face I was aware that the piece of detritus had indeed been transformed into something other than what it had been just minutes before. It was an item of value despite his better judgment. It had become art and in this transition the personal met the politics of responsibility.