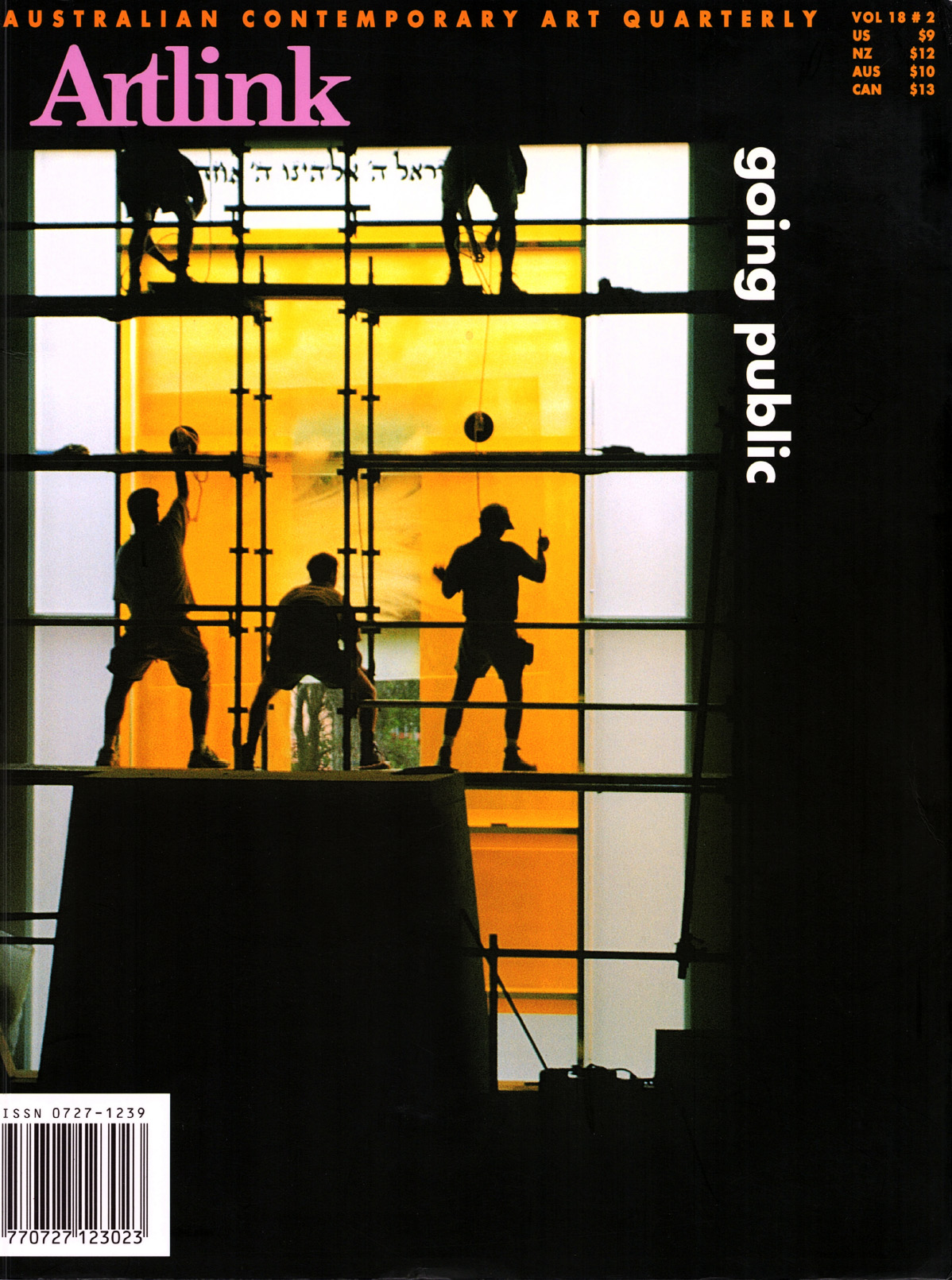

Public Art in Australia

Issue 18:2 | June 1998

The last issue looking at public art was in 1989. Since then the act of putting an artwork into the public arena has become a theatre of conflict, misunderstanding and mismatch of expectations of the parties involved. Issues of community consultation, funding, location, relevance, corporate policy, government involvement are addressed.

In this issue

How the 'Art in Public Places' Debate Shackles Creative Genius

Buckle your seatbelts for a wild, multi-disciplinary ride to explore why all urban space is art... why every individual entering public space is an artist.... how the design of public space either feeds or inhibits this artist.... how professional artists involved in the production of 'public art' should therefore respond.

The Public Interest: Is There Any?

"Living a few hundred metres away from a community arts project has clarified my doubts about the standard and the value of such projects and what they achieve for their supposed audience." Peers explores the current issues facing the production of community and public art looking at 'The Bridge, Construction in Process' an event and exhibition which took place in Melbourne over March- April 1998.

What do THEY make of it?

Jenny Holzer shared some thoughts with Tamara Winikoff during Artist's Week in Adelaide in March 1998 about her relationship with the public, who over the years and in various countries, has been the audience for her artworks in the public arena.

Shelf life, Use by Date and Other Related Issues

Isn't it about time we showed artists and our public artworks a little more respect? We coaxed artists out of their studios to put their creative souls on public display, and now many of those life enhancing objects are looking unloved, forlorn and neglected.

Politics/Poetics: Reflections Documenta

'documenta X' curated by Catherine David from France, opened in Kassel Germany on 21 June 1997 and ran for 100 days. This colossal international event could not be simply understood as an art exhibition and it defied many of the expected ingredients of large scale block busters.

City Provoked: These Questions and More....

RMIT project 'City Provoked' asked questions about the nature of public art emphasising 'new genre public art' - flexibility and responsiveness, specificity and topicality, innovation, challenge, engagement, unregulated encounter. collaboration, temporality and process rather than closure.

The Enduring Moment

It is arguable that temporary public art is a more valid response to the transitory, dynamic and complex nature of the city and public life, more available to be critical and exploratory, than its permanent counterpart.

Five Hundred Sculptors in Melbourne!

Whether Melbourne can support 500 or more sculptors is yet to be proven, but the talent is there and architects, developers and city councils seem to be much more receptive to the concept of public art.

Putting Art in the Landscape

Looks at Herring Island Environmental Sculpture Park, Victoria and the issues which surround putting art into parks and public spaces. Unlike the specialised designs of the contemporary art gallery, the 'environment' is a bundle of concepts distributed across the city and suburbs.

Not Fence Sitting: The Art on Line Project

The 'Art on Line' project initially conceived by Craig Walsh, involved the work of three Brisbane based artists - Wendy Mills, Keith Armstrong and Craig Walsh - who are perhaps better known as working along the experimental edge of fine art, rather than as 'community artists'.

Getting up to Speed in Queensland: The Learning Curve Levels Off

The Queenslanders Art Alliance was established in 1986, maintaining an artist register as well as project management programs collaborating with the Queensland government in the 'Designing Environments' strategy which is intended to consolidate the quality of the collaborative process in public art projects. Looks at the Kangaroo Cliffs Boardwalk project.

The SCIP Project: The Making of Memories in Amnesia Land

Looks at the Sandgate Town Centre Improvement Project (Suburban Centre Improvement Projects) in South East Queensland.

Against the

There's something about public art projects that seems to either bring out the best or the worst in artists. Looks at the 'loo with a view' on the beach front at Mooloolaba on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland. The project has not been without its tensions......

Public Art in Sydney - Olympian Heights or More of the Same?

The Olympic Co-ordination Authority and the Sydney City Council, the two commissioning bodies, have the power to transform the capital with their curated programs of site specific public art, some of which will have a limited life span. Ironically, in these environments where relationship to site is one of the criteria for inclusion, it is left to the artist to reconstruct the histories, to illuminate the voices demolished to make way for Olympic progress.

Bridging Art and Ecology

Over the past decade there has been a significant increase in the number of public art projects directed at the improvement of the quality of public environments. Looks at two projects 'Restoring the Waters' in Fairfield (NSW) involving the artists Michaelie Crawford and Jennifer Turpin and the East Perth Greenway Project by artist Nola Farman. Both projects involve urban waterways and are to do with connecting people to place.

Marking the 2000 Moment: Sydney Pulls Out the Stops

Sculpture is often considered a difficult medium. Public art is frequently controversial. Yet, public sculptural art offers the widest possible audience and the greatest opportunity (by far) to experience, within the increasingly intense landscape of our cities, the humanising and deeply satisfying impact of art and culture.

Commissioning Public Art: A Consultant Speaks

"I am looking at the final design and thought 'what went wrong?' Weeks earlier the Arts Committee had selected an exciting concept design. Why did the artist change the concept design so dramatically?"

Public Art can Kill

Looks at issues of the law and public art with references to Richard Serra's 'Sculpture No.3' and Christo's 'The Umbrellas: a joing project for Japan and USA'.

For Arts Sake a Fair Go

The status quo of moral rights of artists in Australia today in respect of site specific works.

The Vision not so Splendid

Prominent gallerist Paul Greenaway and influential educator Pamela J Zeplin speculated recently about the depths to which confidence in the management of Adelaide's Public Domain has sunk. Who is to blame for the rash of mediocrity -- consultants, governments, artists themselves. Interview.

Fire Rituals for Multicultural Times

Describes the public art event for the 1998 opening ceremony of the Adelaide Festival of Arts -- Flamma, Flamma held at the Torrens River, Elder Park Adelaide SA on 27th February 1998.

A Moment of Reflection

Public Art, the Art for Public Places (APP) program, models for commissions and the matter of percent for art in South Australia. "Processes of development can be as important as the final products when trying to stimulate the field of public art."

An Artist Speaks Out

Challenging work, work that made some form of investigative observation about where we stand at this point in time was virtually not appearing anymore....In Adelaide and other cities, decorative design work, which is often very literal and subservient to conservative briefs, commercial interests, political agendas and restrictive models has appeared everywhere under the name of sculpture.

Local Government and Public Art

Increasingly, local governments at the cutting edge are recognising the need to carefully define their role in public art and more broadly cultural development.

Public Art at the Canberra Museum and Gallery

In a city with so many cultural institutions focused upon the national agenda, the new Canberra Museum and Gallery is a significant symbol of the ACTs (Australian Capital Territory) increasing confidence in a local identity, interdependent with its national role.

Entrepreneurs and Public Art: Private Sponsorship for Public Art Begins to Bloom in WA

Although the history of the west militated against private sponsorship, it began to blossom in the 1990s. This was assisted by the State Government sponsored Percent for Art Scheme. Looks at various examples of public art in Western Australia.

Good or Bad Idea: The Community as Public Art Practitioner

If art in community places isn't for the community using those places, then who is it for? Should all art in public places have immediate community appeal, or reflect those communities in some way, or even have community contributions? And if the answer to any of these is yes, need this impinge on the quality of the art?

Percent for Art in the West

The Percent for Art Scheme in Western Australia uses an allocation of a percentage of the construction cost, usually one percent, of State Capital Works projects to commission artworks. The artist's role is to create works that are integrated with the building or the landscape.

Specific Times and Particular Places: Recent Public Art in Tasmania

Recently there has been a surge of vigorous and challenging public art produced in Tasmania. As well as creating their own opportunities, Tasmanian artists have participated in a wide range of projects facilitated by local and State Governments, festival organisers, corporate entities and private benefactors...engaging with diverse audiences, specific times and particular places.

Need an Artist? Call ArtSource

ArtsWA created 'ArtSource' as an artist's and art consultants register as a means of facilitating best practice in project development and management.

Public Art Practical Guidelines

Book review Public Art Practical Guidelines

Authors Pip Sawyer, Malcolm McGregor, Robyn Taylor

Published by the Ministry for Culture and the Arts

September 1997

$40.00 + $5.00 p&h from the

Artists Foundation of WA

Video

Video review "Talking to Strangers: Public art in Western Australia" Duration approx 40 mins

Produced by the Media Production Unit,

Edith Cowan University,

Western Australia, 1997

Price: $127.00, $99.00 tax exempt

All this and Heaven too

Exhibition review All this and Heaven too Curated by Juliana Engberg The Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

Art Gallery of South Australia

28 February - 13 April 1998

1998 Adelaide Festival Visual Arts Program

Review of the 1998 Adelaide Festival Visual Arts Program

February - March 1998

Artists' Week... Walk that Walk

Review of Artists week for the Adelaide Festival of Arts

1998

Coming Round the Mountain: Excursive Sight

Exhibtion Review Coming Round the Mountain: Excursive Sight

Plimsoll Gallery,

Centre for the Arts University of Tasmania Hobart

17 January - 1 February 1998

Pillow Songs: Poonkhin Khut

Exhibition Review Pillow Songs: Poonkhin Khut

Sidespace Gallery

Salamanca Arts Centre Hobart Tasmania

January 1 - 30 1998

Visual Arts Program: Festival of Perth

Exhibition review Visual Arts Program: Festival of Perth

February 1998

Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions

Exhibition Review Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions Organised by the Asia Society New York

Art Gallery of Western Australia

6 February - 29 March 1998