Warmun Arts. You got a story?

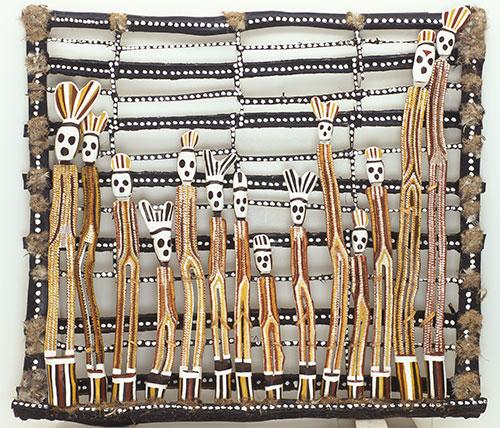

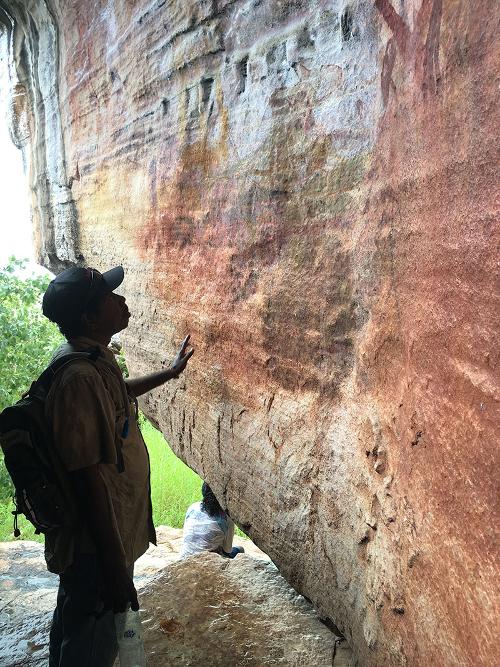

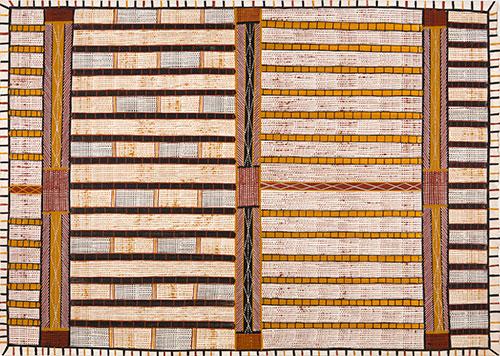

Painting at Warmun has long been linked with the desire of the old people to pass on Gija language to children. At the same time as the Goorirr-goorirr song and dance cycle was given to Rover Thomas by a spirit, Gija elders were requesting that the Ngalangangpum School teach their language. Paintings carried in the dance helped launch the local art movement and the singers and dancers were also the language teachers. They made objects as teaching aids that are now part of the Warmun Community Collection.