.jpg)

The Arnhem, Northern and Kimberley Artists Aboriginal Corporation (ANKA) has welcomed the opportunity to guest-edit the 2016 edition of Artlink Indigenous. ANKA is the peak body for Aboriginal artists and art centres in Arnhem Land, the Kimberley, Tiwi Islands and Katherine-Darwin regions. Through its long-term activities in the areas of support, training, advocacy, referral and regional and cross-regional meeting and shared discourse ANKA has built a strong network of art centres, artists and artsworker members, from diverse language groups and cultures across the north, including some of Australia’s most remote Indigenous communities and homelands. ANKA will celebrate its thirtieth anniversary in 2017. Since 2000 the organisation has an unbroken record of holding four regional meetings, an AGM and annual conference each year. This structure has built the backbone for a strong Indigenous lead and interconnected northern artworld.

ANKA is led by a board of twelve Aboriginal artists and artsworkers elected from its four regions. Linguistic diversity is at its heart, with artists in the ANKA regions speaking in excess of 50 different Indigenous languages. ANKA directors are typically multi-lingual and use English as a necessary lingua franca. Some directors speak as many as seven Indigenous languages.

The retention of languages and their associated cultural knowledge is a high priority for cultural leaders. Language issues vary across the diverse ANKA regions. For example in East Arnhem Land where 88% of all people speak an Indigenous language at home, people face the challenge to build English-language skills, while concurrently preserving endangered dialects and languages. In some other regions, daily use of kriols are common among younger people, with elders speaking local Indigenous languages. Many of the essays, conversations, artist and project profiles in this issue are fully crafted in English, although for the majority of Indigenous authors this is not a first language.

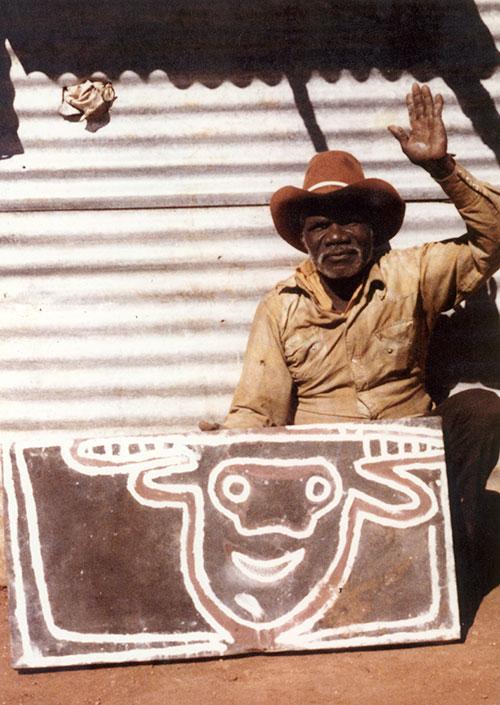

The values of ANKA and the viewpoints articulated in this publication are grounded in a broad philosophy of self-determination, which gained legislative authority in Australia in the 1970s when the Australian government introduced platforms for land rights and self-determination, replacing previous assimilation policies. Through the 1970s Aboriginal initiatives led to a widespread movement of people returning to establish homeland or outstation settlements on or near their ancestral countries, which clans had earlier been forced to leave, relocated to “centralised” missions, settlements and reserves.

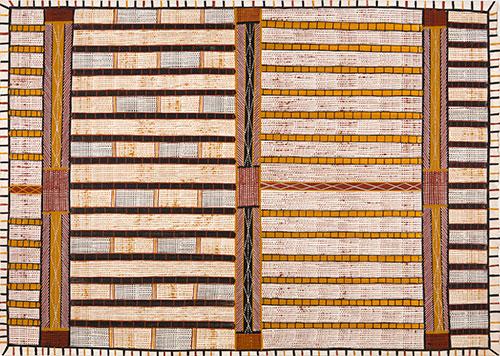

As foregrounded in several articles in this issue, homelands and outstations remain vital to the contemporary Aboriginal art movement, which accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s with the return to country. Today, many Aboriginal-owned community art centres are situated in larger Indigenous communities sustained by artists working in homelands and outstations. It is almost universal that artwork created and sold through Aboriginal-owned art centres either refers to or is literally and materially created from the fabric of ancestral country (through the harvesting of ochres, barks, pandanus, bush vines and dye from plant roots and leaves).

The linguistically and culturally diverse artists profiled in these articles have many core values in common. In particular, a dedication to ensuring intergenerational sharing of traditional knowledge and care for country. Intergenerational knowledge exchange is a key focus of the article on the Yirrikala-based Mulka Project, a dynamic multimedia archiving and production enterprise, which gives exemplary practical realisation to aspirations held by most other art centres in the north to work collectively to keep cultural heritage alive for upcoming generations and for the benefit of the contemporary world.

“Working together to keep art, country and culture strong” is the long-held ANKA mission. This reflects an integrated worldview where “art, country and culture” are inextricably interconnected and where, far from being autonomous or embodying an “art for arts sake” philosophy, art practice is typically intricately bound up with practical land-care and ecology, sharing of invaluable traditional knowledge, and agitation to transform the world. Contemporary northern Indigenous art is often a weapon, a title deed, a talking stick, a means of economic empowerment and a crafted philosophical space.