Revealed: We are a sovereign people

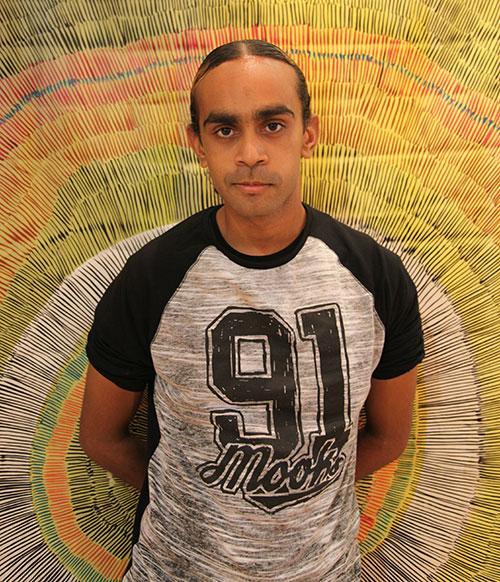

Keynote address presented on 17 April 2015 in Perth as part of the annual Revealed program supporting emerging Aboriginal artists from Western Australia.

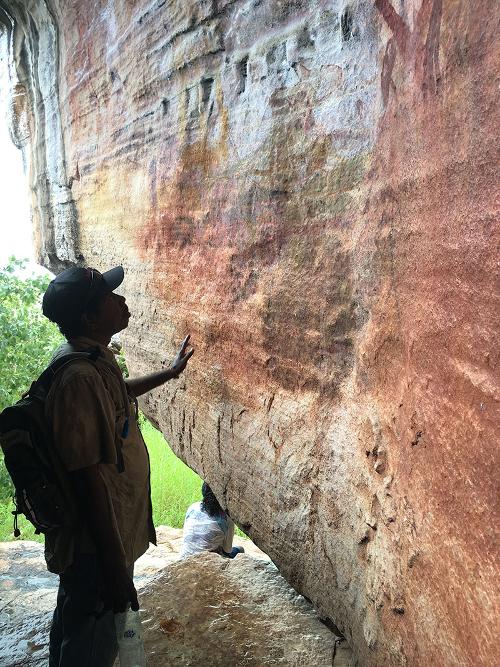

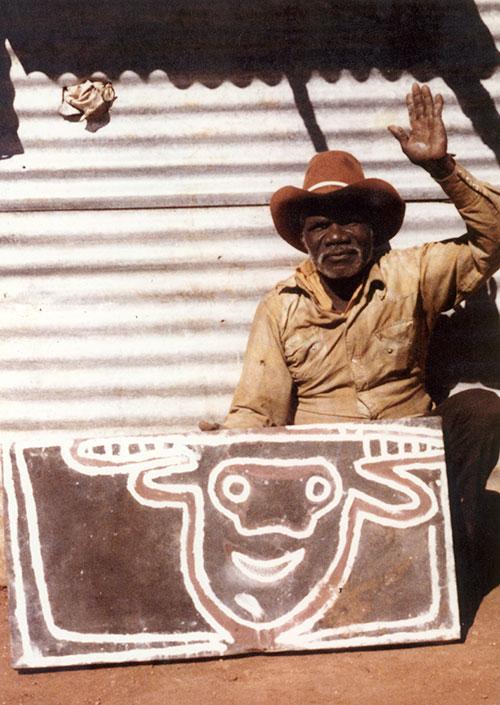

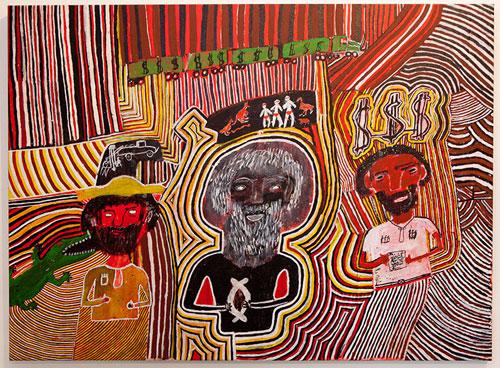

As Indigenous people of this nation we are a sovereign people, standing strong in our culture and remaining true to our heritage. We stand strong in our art; we stand strong in our culture and we stand strong on our country. Our ancestors, communities and families have welcomed many non-Indigenous peoples into this country, and today we see the continuity of our shared culture, history and traditions. I see Aboriginal art and culture at the very forefront of Australian identity and celebrated in such a way that previous generations would not have imagined. Despite these remarkable achievements, we as Aboriginal people in this country have been continually bombarded by waves of dispossession, racism, marginalisation and genocide. I am both angered and frustrated that we continue to sustain the impact of colonisation on a daily basis some 226 years after invasion. We are not recognised as a sovereign people, we continue to be governed by a nation that does not recognise us as equals.