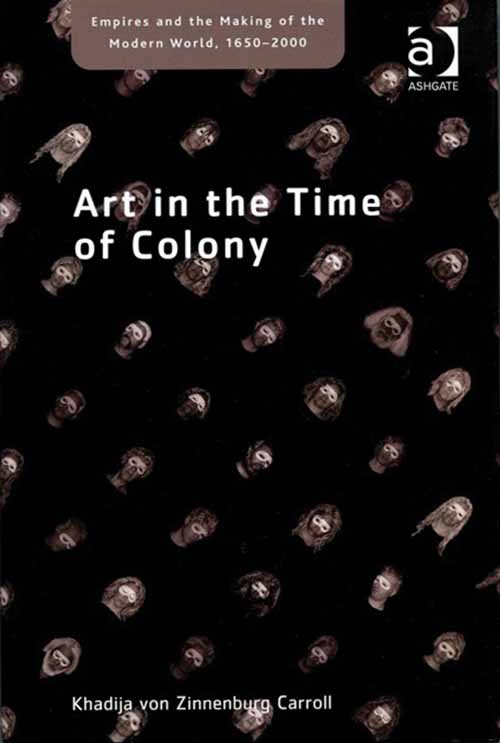

The fascinating premise behind Khadjia von Zinnenburg Carroll’s Art in the Time of Colony is an examination of how contemporary art has been used to stand in for gaps in the historical record of Indigenous Australians.

Through a series of case studies that juxtapose nineteenth-century and contemporary creative resistance and responses to colonialism, Carroll effects a reversal of the concept of art history: art is shown to contribute productively to the revision of history and the production of knowledge. For example, the juxtaposition of the art of Julie Gough and the Tasmanian Picture Proclamation Boards of 1829/30, or Vernon Ah Kee’s artwork with drawings by Yakaduna/Tommy McRae demonstrate the inventive and critical re-production of history from an Indigenous perspective by Indigenous artists.

Carroll is an academic, curator and artist and all three roles are drawn upon in her book. Originally conceived as an exhibition, the work is a self-proclaimed ‘‘museum in a book’’, a form of exhibition requiring ‘‘the independence of the reader rather than the locatedness of a temporary exhibition’’. Carroll brings together art history, critical theory, the history of science, anthropology and contemporary art practice in her work.

Her own artistic practice is included through her analysis of the Koori Possum Skins Cloak project, a collaborative project she participated in from 2007-13, culminating in the film Skins Cloak. Paradoxically, the inclusion of a number of her own photographs, many of which are taken through a microscope, mimic a taxonomic scientific analysis, the authority of which her work sets out to challenge.

Mimicry and anachronism are central to Carroll’s methodology and approach. Anachronism is defined in a pseudo-Derridean manner as ‘‘the recurrence of being out of time’’ and is used to open up the historical archive to demonstrate the inclusion of the excluded in contemporary art.