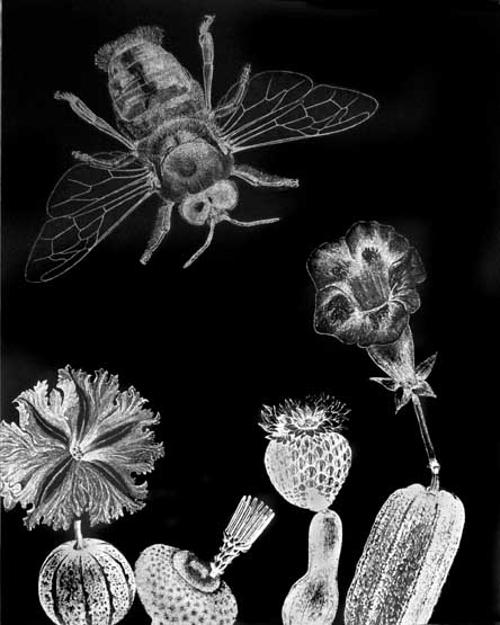

One of the perennial issues that arises whenever documentary photography is discussed is the suitability of the 'white-box' gallery as a space in which to present this kind of work. Does the stiff formality and emotional sterility of the gallery promote a socio-political dislocation between the patrons of these spaces and the lives of the people whose stories are being depicted?

The Museum of Brisbane recently presented an exhibition that serves as a good test case to support an argument that provocative documentary imagery can in fact work very well in a public gallery space. It presents a survey of a decade and a half of work by the Brisbane-based partnership of documentists Angela Blakely and David Lloyd with a selection of images from several of their major projects produced both abroad and in Australia.

The work is certainly powerful. It is visually compelling, perhaps even (starkly) beautiful but it is not a comfortable viewing experience. The individuals depicted are presented with a defiant determination that disallows any interpretation of victimisation, despite the very real problems of the situations in which they may find themselves. These images invite us to imagine ourselves in the difficult circumstances documented but they do not welcome any unctuous, hand-wringing pity.

Because of major renovations occurring at the usual site of Museum of Brisbane, the exhibition is displayed in a temporary space that is somewhat tomb-like. Low ceilings, dark walls and small partitioned cells of space emphasise the scale of the large images that you encounter as you navigate the labyrinthine configuration of the gallery. These physical aspects of the exhibition help to create an intimacy that works against the potential problems of sterile white-box galleries discussed above but many of these images can and have been successfully exhibited in larger, more open spaces. Viewing audiences engage very well with the genre of social documentary photography when they are offered work by gifted practitioners who can find points of universal references within specific circumstances (and this is indicated by the visitor numbers that have been generated by previous shows of documentary photography at the Museum of Brisbane). At its best, this kind of photography manages to tell stories about individuals who are unknown to us, in a way that evokes and provokes responses that derive from our own experience.

This is seen very clearly in the series Mt Isa (2006) a four-year project documenting the fractured sub-cultures of indigenous youth in rural Queensland. The project involved local agencies and communities in an attempt to find various methodologies of representation to give a voice to the marginalised youth whose lives it documented. One of the images from this series (entitled Spiderman) depicts a young boy who is dressed up in the costume of a superhero. Hardly a remarkable occurrence in 21st Century Australia but the image demands a closer examination that might start with ideas/questions like the following. In the brief period since British colonisation of this country we have gathered enough history to generate an accompanying body of myth and a small pantheon of heroes like Captain Cook, Don Bradman and Steve Irwin. That narrative has been imposed on top of an indigenous history that is at least 40,000 years deep. Given all this, why does the child depicted reject both traditions and look for his heroes in the popular, comic-book culture of another nation state? Is our country so utterly disconnected to any sense of itself that we feel more connected to the radioactive spiders of Peter Parker’s New York than to any of our own stories?

If there is any problem with this exhibition it is the lack of faith in viewing audiences that is demonstrated in the curatorial decisions made by the Museum. Clearly a survey of seventeen years of practice by this prolific partnership has to be highly selective but anyone with even a slight familiarity with Blakely & Lloyd can be excused for thinking that this selection is so very ‘safe’ in its avoidance of confronting imagery that it distorts and dilutes the power of their work. Certainly their long-term project working with communities in Rwanda suffers from the apparent timidity of the editorial policy.

That project (Never Again - Stories from Survivors of Genocide in Rwanda) is an extremely important body of work that needs to be seen by a wider viewing audience. Some of the visual stories that came out of this project are intensely confronting but this cannot be an excuse to shield us from an engagement with the human cost of this tragic episode in our recent history. Perhaps the photographic publishing industry that is (finally) developing in Australia offers some hope of getting the work seen. In the meantime, the Blakely & Lloyd survey exhibition presented by The Museum of Brisbane is a good introduction to the contribution these two visual practitioners continue to make to the discourse on the rights and responsibilities of human society.