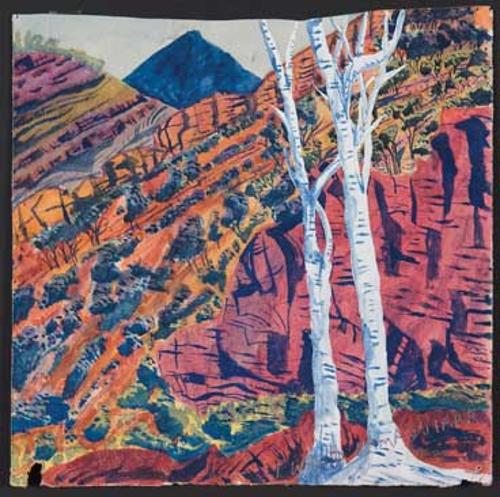

Julie Gough's canvas skillion invades the lofty setting of the Devonport Regional Gallery: a converted Baptist Church with a vaulted, blackwood ceiling. Titled Trespass II, the 'walls’ to Gough’s structure are modelled on a grazier’s roughly hewn fence and stencilled with the names of properties whose owners were complicit in Tasmania’s notorious Black Line of 1830. Many of these properties continue to prosper nearly 200 years on. There is no door to Trespass but inside is a stretcher bed with a kangaroo skin blanket and pillow, ruffled as if just occupied. A coat hangs on a peg and tea tree spears protrude horizontally from the bed-ends.

Trespass II is an apt centrepiece to Gough’s exhibition Rivers Run. Its direct physical relationship to the church creates a pertinent context for a body of work about the trauma inflicted upon Tasmanian Aboriginal people by colonists and the ongoing impact of this genocide. Looking like a traditional trapper’s hut, it suggests both home and temporariness, presence and absence, the hunter and the hunted. It might be a shelter for Gough’s Aboriginal ancestors, or for the artist herself. Nevertheless it is ruthlessly bound by the names of properties that make up white Tasmania.

The surrounding works in the exhibition are nearly all about running and movement as actions of escape and re-discovery. In Driving Black Home 2 2009, and Rivers Run 2009, we see evidence of the artist brushing beside the same properties which feature in Trespass. They are filmed from a car window as she travels along highways and back roads, and from a canoe which sneaks through farmland via river systems. The camerawork is frenetic - a reminder of the unauthorised nature of the artist’s mission. The footage is overlaid with historical text citing details about land grants to early settlers and letters written by white people informing the Governor of killings by the Black Natives who ‘infest the neighbourhood’. The text runs quickly - just enough for us to catch its tone, but not allowing the luxury of absorbing information. The absence of black stories is deafening.

We ran/I am 2007, possesses similar intensity. Fourteen images document the artist retracing the Black Line on foot – running and stumbling. Seven pairs of the earth-stained calico trousers she wore at key sites hang below the photographs. They have been made to resemble the trousers issued by George Augustus Robinson to his Aboriginal party. Gough quotes his diary in the chilling remainder of the work’s title: 3 November 1830 ... ‘I issued slops to all the fresh natives, gave them baubles and played the flute, and rendered them as satisfied as I could. The people all seemed satisfied with their clothes. Trousers is excellent things and confines their legs so they cannot run’. Here, the instinctual and desperate act of running contrasts with the cool, ordered process of taxonomy typifying Gough’s knack of spinning together felt response and historical fact to create astoundingly astute and moving works of art.

History has informed Gough’s work for nearly 20 years. She has mined Tasmania’s archives and assiduously collected objects and materials to build up an idiosyncratic and compelling visual lexicon. In Rivers Run – as with nearly all her work - the materials alone are evocative: kangaroo pelts, tea tree, felt dyed ‘red-coat’ scarlet (the authentic dye sourced from England), straw bales, and a found hay fork. Although Rivers Run might have been conceived as a mini-survey (the 10 works span 11 years), the exhibition remains bound by a tight conceptual framework and it is plausible that all works might have come from one body. This is partly because the central work, Trespass II, is such a strong anchor, or axis, for the surrounding pieces. But it is primarily because the tight connections throughout the exhibition are testament to Gough’s unwavering focus and continued reinterpretation of the past from her informed, ever-adapting contemporary perspective.