Tell Me Tell Me: Australian and Korean Art 1976-2011 probes the fundamental nature of art and provokes the viewer to consider and question it from several angles. Through this process, layers of cross-cultural complexity are unpicked and explored through a lens spanning three decades.

Entering the exhibition is like opening the door to a cabinet of curiosities. Artworks, objects, specimens and archives are cobbled together in the gallery space in a bibimbap (Korean mixed rice dish) of ideas, theories and exercises in conceptual, anti-form and post object art. The exhibition is a major project of Sydney's Museum of Contemporary Art, currently closed for redevelopment, and has been conceived in response to the Australian-Korean Year of Friendship which celebrates 50 years of shared diplomatic relations.

The discussion commences in 1976, a time when both countries were beginning to lend their own voice to the global dialogue on the evolution of art. Australia was anchoring one of the world’s first contemporary Biennale programs in Sydney (the first commenced in 1973) while Korea was demonstrating a unique versatility through the Mono-ha works of Lee U-Fan while simultaneously initiating a paradigm shift through the groundbreaking video and performance art of Nam June Paik.

The curatorial vision of the 1976 Biennale of Sydney, Recent International Forms in Art, pushed beyond painting to explore the place of object as art and the relationship between object and event. It brought together the works of a diverse group of artists, including four Koreans whose work was shown alongside their Australian contemporaries for the very first time. Tell Me Tell Me reignites the discourse that began in Sydney 32 years ago and considers how artists in subsequent generations have explored the ambiguities between art and non-art.

In 1976 Sydney audiences were given a combination of stimulation and scandal. Tell Me Tell Me pieces together archival footage of one of John Kaldor’s early projects which saw Nam June Paik’s muse Charlotte Moorman play an ice cello in the nude (Ice Music for Sydney 1976). She was later to be coated in chocolate (Candy: The Ultimate Easter Bunny 1976) and in due course suspended in air above the sails of the Opera House (Sky Kiss 1976).

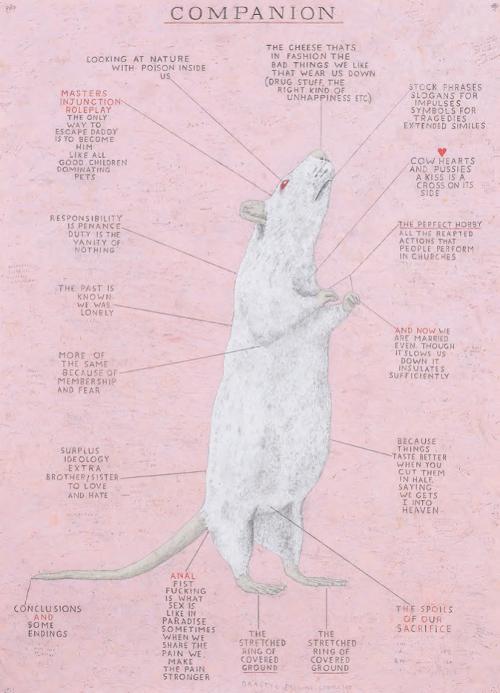

Death-defying acts of suspension were taken one step further by Stelarc who, tethered by hook and string, was hung in the Art Gallery of NSW (Event for Stretched Skin 1976) above a large boulder and a laser beam. Tell Me Tell Me unearths still and video images of this gruesome performance, exhibited beside the blood and rust-stained tackle used in the original performance.

The placement of natural elements, particularly stone, a symbol of nature, strength and resilience central to Korean cultural imagery is a constant throughout the exhibition. As a derivative of earth, stone is also interwoven within the traditional five elements of Korean culture: fire, water, earth, wood and metal. These 'oh hang’ elements represent the fundamental energies that create and unite all creatures. Insik Quac’s Work No 11 and Work No 13 (1976) comprises two stones marked with dots in a circular motif. Bonita Ely and Marr Grounds’ Austausch/Exchange (1984) combines stone blocks and feathers contained within a wooden box. Both works comment on the vague boundaries between art and non-art.

The incorporation of Australian Indigenous art sits at odds with the conceptual and post-object themes of Tell Me Tell Me. Don Gundinga’s Stone axe totem (c1970), Lalara Gaiyabidja’s Untitled the travelling rock (c 1970) and Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s Untitled Alhalkere (1992), do not illustrate the development and progression of conceptual art in Australia and Korea and their links and relevance to the exhibition are tenuous. However, the lens through which we view Indigenous art, where meaning can shift depending on context, can also be applied to the way in which the viewer interprets experimental performance and art. Many of the works included here share a common 'earth based’ source of origin and reference interruption to natural landscape and environment.

The placement of Rosalie Gascoigne’s landscape Set Up (1984) on the first floor of the exhibition serves as a masterful framing device as it illustrates one of the central tenets of the importance of the placement of objects in space. Gascoigne’s measured assignment of utilitarian white enamel vessels upon a crosshatched topography of wooden panels is striking in both form and in its interplay with the gallery space. Her assemblage of aged enamelware evokes the revered milk white porcelain of Korea’s Choson Dynasty. These austere white vessels reflected the noble virtues of honesty, purity, simplicity and restraint that were so important in Korea’s Neo-Confucian social order. Conceptual objects themselves, these ancient vessels are studies in simplicity and reduced form.

Further ancient references can be found in the pagoda-like stacks that appear in several forms throughout the exhibition. From Hyun-Ki Park’s Untitled (1986) assemblage featuring piled TV monitors sandwiched between two stones to Kang-So Lee’s Untitled (1994) bronze pile of Confucian texts, the works stand like the shrines to a guardian deity. The exhibition concludes with a giant meccano-like totem by Bob Jenyns Brancusi (2006), which perhaps stands as a symbolic reference to the 21st Century deity of relentless commercial development.

While the conversation was at times awkward and disjointed Tell Me Tell Me: Australian and Korean Art 1976-2011 definitely succeeded in reviving a valuable dialogue on the origins and evolution of post-object art, conceptual performance and video art. As significant trading partners, Korea and Australia share many common interests, not least of which is a vibrant, dynamic collection of artists. With a 50 year heritage of building successful business partnerships our two nations are well-positioned to leverage more successful, more frequent artistic partnerships in the future.