I recently and unexpectedly came across Martha Rosler's iconic work Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) at Queensland Art Gallery. Sitting quietly through the video I found myself taken back to the past. The spoon, the knife, the jerks and thrusts of Rosler’s actions stirred and jolted my memories back to my aspirations as a young girl in the 70s and to thoughts of my Feminist art heroines. But before the allure of nostalgia took hold I was gripped by the force and relevance of this work to artists today - confronting anew our identities, our desires and our power.

Thus I was eager to see more Feminist art, in particular by local practitioners, in this important exhibition at MUMA. Unlike most Modernist art movements where Australian art lagged behind its international counterparts, where Feminist art is concerned there was and is no such cultural cringe. Current international debates encircled these artists, including direct dialogue with Lucy Lippard, Mary Kelly and Laura Mulvey. Hence we need not be concerned about a nationalist agenda in this show, rather we are invited to consider the choice of artists within their geographic and temporal limits through the insightful curatorial rubric of stratagems of durationality.

So in considering this pivotal exhibition, I am again struck by leaps through time. Serendipitously, but by no means coincidental, Rosler’s video was made at the beginning of the interval dictated by Kyla McFarlane’s curatorial parameters – the radical ten years when Feminist art shifted astride multiple, passionate discourses of female representation, psychoanalytic theory, semiosis and new media and performance processes.

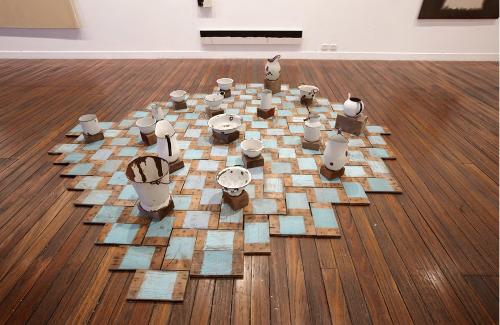

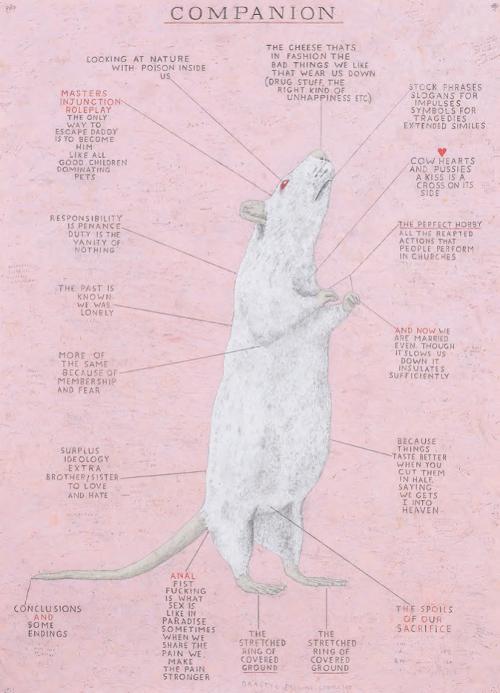

The works on show at MUMA capture the range of contested issues for Feminism in the 70s and 80s; the body, the domestic, social justice, environmentalism and power politics. Upon entering the gallery, the first work I encountered sounded the rallying cry "silence is not a strategy!" in Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley’s Story of a woman who... found herself trapped in a sociological nightmare (1983). There are a number of works by this collaborative team on show, whose confluence of politics, art theory and popular culture produces a consistent array of ironic and subversive works.

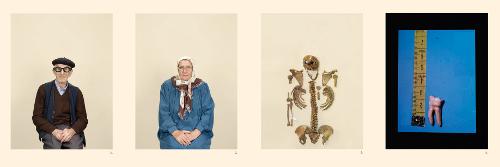

The dominance of photography, experimental animation and film processes across the three galleries highlights the radical exploration of art mediums during this period. Micky Allan’s People of Elizabeth series (1982-83) poetically dwells on the threshold between the handmade and the technological through her process of hand-colouring photographs, whereas Helen Grace fully embraces the photographic medium and later moves to animation and film. Grace’s Xmas dinner series (1979) a study of the domestic and collective nature of 'women’s work’ is eloquently reconfigured as a DVD in The immortals (1979/2005) inflected with the political changes that took place in the interval.

Sue Ford similarly revisits her subjects a generation later in the captivating work Faces 1976-1996 (1996) (version on show re-edited 2011, by Sue Ford and Ben Ford). In contrast, Jenny Watson’s oil painting A painted page 5: The Sun Jezza will stay, Blues (1980) strategically depicts a snapshot from just one day’s local print media.

Bonita Ely’s sustained use of personal narrative, archive, scientific data, performance and traditional art-making forms is demonstrated in the suite of works exploring the Murray River. This ongoing project sets a benchmark for environmental art and its subject is poignantly still a site of contention today. Complementing these works, Lyndal Jones’ At home series (1977- 80) and associated works foreground her sustained deconstruction of political and social canons through a commitment to performance strategies.

A thorough and scholarly catalogue accompanies the exhibition, including archival documents and illuminating, previously unpublished material. This can only extend the duration of this focussed exhibition. As the titles suggests, temporality is used as a conceptual and material medium, notwithstanding, this exhibition deserves time to view and experience in full. The scope of works is dense and challenging, yet time well spent, I’d say.