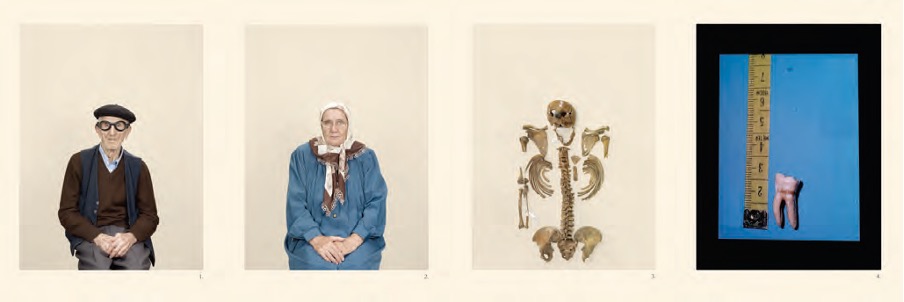

1. Nukic, Nezir, 1928 (exact birth date unknown). Forester and road builder. Zivinice, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

2. Mehic, Zumra, 09 Dec. 1950. Homemaker. Kladanj, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

3. Mehic, Bajazit, 16 Sept. 1972 – 11 July 1995. Mortal remains, International Commission on Missing Persons, Podrinje Identification Project. Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

4. Mehic, Ahmedin, 16 Feb. 1974 – 12 July 1995. Tooth sample used for DNA matching, International Commission on Missing Persons. Srebrenica-Potocari Memorial and Cemetery, Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. © Taryn Simon. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

It’s difficult to know where to begin when it comes to the work of American artist Taryn Simon. The complex, systematic and detailed nature of her practice, as evidenced in her current exhibition at Tate Modern A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters has been described variously as conceptual, scientific and thought-provoking if not profoundly philosophical in its explorations of the interconnectivity of life, fate, family, history and politics.

Simon is generally regarded as a photographer but the interdependence she creates between image and text in realising her meaning is so central to her work that to call it simply photography is to create more problems than solutions.

A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters is the culmination of four years of work, of which only two months were spent actually taking photographs. From 2008 to 2011 Simon travelled the world with a team of translators, fixers and fact-checkers researching and recording different bloodlines and their concomitant tales of struggle and survival, almost in spite of the odds. Themes of territory, power, circumstance, inheritance (both physical and psychological) and religion infuse these 18 chapters, which include thalidomide victims, albinos in Tanzania, feuding families in Brazil, a polygamist Kenyan medicine man and Uday Hussein’s body double. In discussing the exhibition Simon has said it is: “easily the most difficult and demanding project I have done thus far” and went on to explain: “I don’t have an agenda (but) I guess a lot of what I do is underpinned by anxiety.”

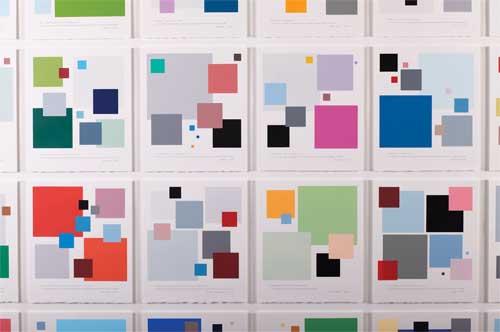

This anxiety is certainly palpable in the presentation of her research. Each chapter is represented across three distinct panels - the photographic portraits; a text panel outlining each member by name, date of birth and current location together with their 'family story’; and a panel of footnotes – arbitrarily placed secondary source materials that allude to the messiness and complication of these existences not seen in the structured portraits and text. This combination of image and text, as well as visual structure and disorder is oddly both relentlessly clinical and darkly poetic in its bigger picture exploration of what is ultimately the perilousness of fate.

It makes for an intoxicatingly uneasy but absorbing viewing experience.

Viewed at large, the portraits present almost as a periodic table and are based on the limited genealogy of a single bloodline. They start with Simon’s designated ‘point person’ and include any direct living ascendants before following the descendants from oldest to youngest in each generation, repeating until all living descendants have been presented or accounted for. In every chapter the portraits are presented in this same way, each also photographed against the same white background, in the same pose, wearing the same blank expression. Those dead, missing or otherwise unable to participate are accounted for with an empty square. As portraits they give very little away.

The title for the exhibition comes from the first chapter concerning Dhainey Yadev, an Indian man who was declared dead by relatives so they could claim his land as inheritance. As Simon’s photograph shows, Yadev is very much alive but while the dispute is unresolved and attempts are made to ‘revoke’ Yadev’s death, he and his family remain displaced and the ancestral home remains unoccupied.

The family of Hans Frank, Adolf Hitler’s personal legal advisor and the Governor-General of Poland during the Second World War, make up the bloodline in Chapter XI. Frank was executed in 1946 but his bloodline includes 26 portraits, eight of which are blank while another four are represented by a pile of clothing sent as representation. Another sits, pixellated, with his back to the camera. In the text panel Frank’s appearance at the Nuremburg trial is recounted, where he claimed to have tried 14 times to resign without success. The veracity of his defence is not explored but it sits uncomfortably between a portrait of his most recent descendant, Nora Frank, born in 2007 and the footnote panel featuring images of works by da Vinci, Rembrandt and Raphael. These paintings were stolen by the Germans from the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow and were last recorded to have been in Frank’s apartment at the end of the war. Two were returned to the museum while the third Raphael’s Landscape with the Good Samaritan remains unaccounted for.

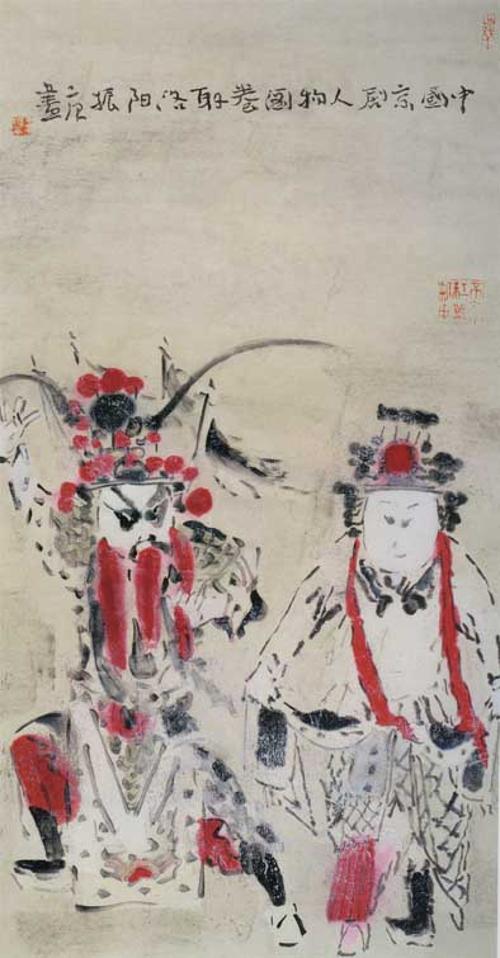

War is a recurring theme throughout Simon’s researched and carefully curated bloodlines and the Bosnian genocide of 1995 and the family of Nezur Nukic are the subject of Chapter VII. There are 10 portraits in this bloodline and four descendants are represented by what remains of them – an incomplete skeleton retrieved from a mass grave; teeth; and part of a single bone. Photographed like the medical specimens they are, the text explains that they were just four of the 8000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys murdered in Srebrenica and that the teeth and bones were only identified using blood DNA samples from remaining members of the bloodline. Simon’s footnotes include a photograph of some of the personal effects found in the mass graves – combs, glasses and forlorn cigarettes. These personal effects are arguably more effective than the shard of bone in conveying the gross violence suffered by these teenagers and the loss suffered by their family.

The chapters are not arranged numerically in the rooms but even if they were, the subjects of Chapter VI would make for an intriguing interruption to what otherwise amounts to a fairly bleak walk through modern history. Chapter VI explores the bloodlines of No.1624, No.2146 and No.1628. Rabbits. As Simon’s text panel explains, in 1859 twenty-four rabbits were introduced into the wild in Victoria, Australia for hunting purposes, only for half a billion rabbits to exist by 1959. Despite the introduction of several lethal diseases including the calicivirus and myxomatosis, the rabbits continue to develop strains of resistance and with no natural predator the animals now cause agricultural and environmental damage to the tune of $600 million annually. Their persistent survival is an expensive and frustrating lesson in how to adapt, recover and survive as they continue to suffer their own versions of attempted genocide. And as the Haigh’s chocolate bilby in the footnotes reveals – nothing is sacred when it comes to re-writing history and historical traditions. So long chocolate Easter bunny.

These are but four of the 18 chapters that make up A Living Man and in considering the whole show both as art and historical evidence two things become clear. The first is what Homi Bhaba has identified as Simon’s “profound ambivalence towards the testimony of photography’s truth”. The second is the artist’s deft ability to resist her work turning into a catalogue of voyeuristic horrors and to instead present a nuanced but articulate meditation on history, narrative and fate. There is little sense of redemption in Simon’s work but there’s a strange sort of reassurance to be had in her clinical methodology and aesthetic – a false sense of order and purpose to the madness of life. Simon has said: “It tries to consider this idea that we keep going, people keep being produced but does that all amount to some sort of evolution or are we on repeat? I don’t know that there is an answer.” I don’t either.