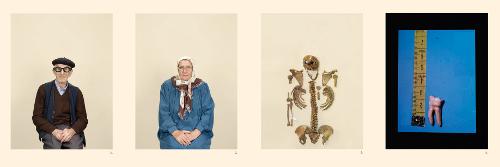

Bernard Smith 1916-2011

Australian and Un - Public memory and the neo-Smith canon

Bernard Smith, 1916-2011, was a fixture in art history circles in Australia for seven decades. Engaged and committed, he was still writing complex, insightful narratives about art into his eighth and ninth decades, and inter alia vigorously defending any incursion on or critique of his imperium. His passing marks not only the end of an era for art history in Australia, but he was perhaps the last survivor of those towering, paternal, left of centre figures who so greatly influenced and surveilled, rightly or wrongly, the interpretation of Australian culture and the development of humanities scholarship in post-war Australia. Many and extravagant were the tributes to Smith after his death, frequently quoting not his living peers but an essay from the 1990s by the late historian and anthropologist, Greg Dening reviewing Peter Beilharz's equally hagiographic monograph tribute to Smith. Yet it must also be remembered that outside of the spotlight of the credibility bestowed by Smith’s narrative of Australian art that he commenced with lectures and exhibitions in the 1940s, many artists lingered unappreciated and overlooked, particularly because historians, curators and collectors in the third quarter of the twentieth century more often than not relied upon Smith’s judgements, rather than looking at artworks for themselves. His focus on the collections of the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the art of Sydney and Melbourne, where most of his working life was spent, as the backbone around which to organise his historical narrative, begot an art history that has tended to be Sydney-Melbourne centric and peopled by a succession of mainstream male artists, even if the tale of Adelaide Ironside, the first Australian artist to study in Europe, struck a chord for its curiosity value. Despite his magisterial status, there are surely too many bodies buried, too many overlooked artists. One thinks of excellent artists outside of Sydney and Melbourne, the many women artists hardly mentioned in his surveys, the expatriates in Europe and Britain, the Edwardian academic artists, the artists who moved between Australia and New Zealand, the Australians who worked in the United States and most particularly nineteenth century academic artists, all of whom are outsiders in the set narrative, all of whom are what Rex Butler nominates as Un-Australian artists, partly because of their invisibility in the neo-Smith canon. Smith’s antipathy to nineteenth century academic art was de rigeur amongst international scholars in his formative years, but possibly the respect given to values established by Smith has meant that this prejudice has taken longer to dissipate in Australia than elsewhere. There was only one substantial rethinking of his narrative, only one concession made to the previously overlooked, with his 1980 Boyer Lecture series for the ABC, when he suggested that any cultural discussion in Australia must foreground Indigenous issues and histories. The challenge that he laid down for other humanities academics is one of several prophetic leaps of analysis that he made during a six decade career as a public intellectual.

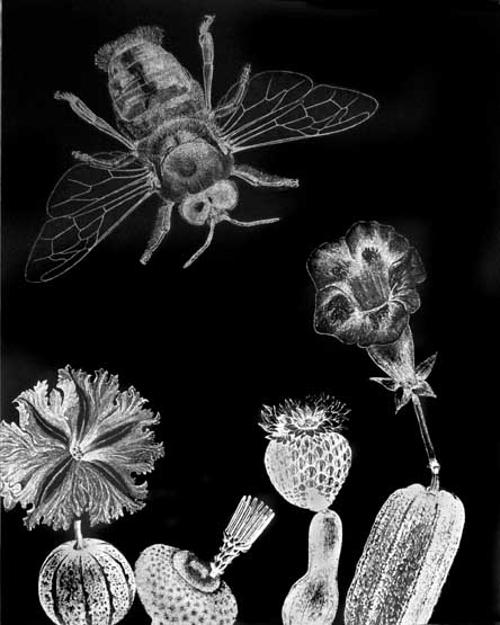

Smith’s greatest achievements lie outside his longitudinal surveys of Australian painting and in a more international context. He anticipated a number of key trends in recent visual art scholarship not only in using the word postmodernist in published texts in 1945 and reading the dominant cultures from the margins to establish a post-colonial vision as early as the 1950s, but also in examining the enlightenment as the wellspring of modern cultural ambition and sensemaking. Whilst in recent years the art and science cross-over, such as discussions of Darwin and art history, is commonplace, Smith had already identified in the 1950s that empirical drawings and sketches collected in the Pacific by early explorers and scientists in the eighteenth century provided the means for a transformative rethinking of the nature of man and society during that era. He developed a longstanding and indelible international reputation as a scholar of the art of early Europeans in the Pacific and his essays appeared in European and American publications. Here his catchment of valid works was more flexible and expansive as knowledge of the field grew via scholarly collaboration across several countries and over three or more decades. Despite the fraught relationship between Smith and Victorian painting, his active contribution to urban heritage preservation in the early 1970s and the documenting with his first wife Kate Challis, of early architecture in the Sydney suburb of Glebe merits more recognition than it currently receives and again was cutting edge for its time.