The Mad Square has been a long time coming. It is the first time Australia has seen an exhibition that enables serious visual analysis of the art that contributed so much to the world in the years after World War II. The people who left Germany and Europe because of the Nazis did good wherever they went, and in Australia their influence has been profound. Some of our immigrant artists (Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, Wolfgang Sievers, Margaret Michaelis) are represented at last in the context of the world that shaped them.

The curator of The Mad Square, Jacqueline Strecker has aimed at an examination of the broad sweep of visual history. She tracks that heady time when Germany celebrated the optimism of soldiers as they marched off to the Great War; and in the following decades saw despair, violence, starvation, and the rise of the Third Reich.

She has shaped the exhibition in part around her 1995 PhD thesis: "The mad square": the Prussian Academy of Arts and Modern Art in Weimar Germany 1918-1933 which provides both the title and a restricted time frame. 1933 was the year Hitler seized power and the first waves of refugees fled. 1937 is the year of the most infamous of the Degenerate Art exhibitions, when the Nazis displayed the art they loathed - which of course included much that we now admire. It was worth extending the exhibition to this date as it is an important cultural punctuation point, and it is exciting to see some of the actual works that were ridiculed. Likewise it makes sense to begin before World War I, a time when German culture was on the ascendant as artists like Kirchner bounced off the liberation of colour and form that they had absorbed from Van Gogh and the Fauves. This was followed by the terrible disillusionment of the reality of war, and a search for the visual language to express this.

Exhibitions are an exercise in pragmatics, so it was never going to be possible to borrow Max Beckmann's masterpiece painting The Night (1919), but Beckmann was a great graphic artist and his black and white lithograph version shows the allegory of the terrible destruction of family, of intimacy, and the rise of madness: a destruction witnessed by a child who will be condemned to fight the next war. But this is the first disappointment. Instead of giving viewers an idea of the underlying anguish of Beckmann’s response to war, the caption describes it as “...a gang of criminals forcefully interrupting a family gathering” and while it notes “...that violence and political extremism invaded every aspect of life in post-war Germany” rather than giving context to the work, the information serves to diminish the power of Beckmann’s achievement.

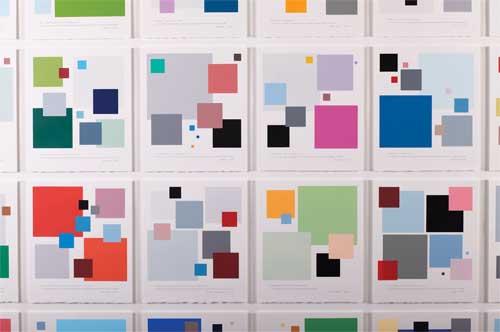

This muting of the harshness of history is also seen in the account of the closing of the Weimar Bauhaus in 1925 “because of its perceived cultural Bolshevism”. It would have been useful to mention that those opposing the Bauhaus were the Nazi party, which after 1924 had the balance of power in Weimar. The intensity of the political to and fro that saw Germany swing between the Spartacists of the left and the Nazis of the right, is shown best in political posters and the savage photomontage of John Heartfield. Other artists, designers and filmmakers reacted to the times by inventing new visual languages to describe the violence and the grief of mutilated soldiers and scrawny prostitutes, trying to live in a world without compassion.

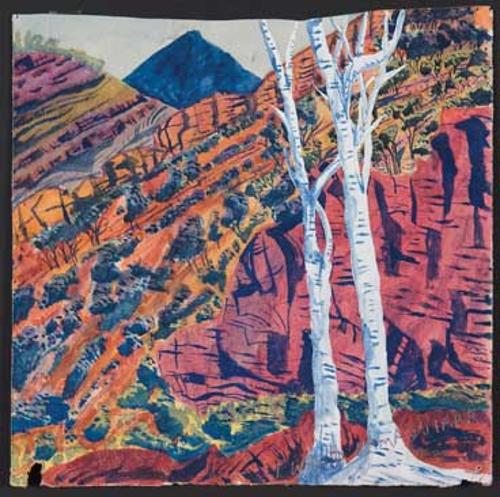

At the very heart of the exhibition is a room of Neue Sachlichkeit (new objectivity) portraits, representing the world in which these artists and subjects found themselves. It is however a reality where people adopt personas for self-protection, where the only sane stance is irony. One of the most beautiful works here is Otto Dix’s joyous Portrait of the Dancer Tamara Danischewski (1933). She is blonde, beautiful and stares directly at the viewer. As a part of his signature and next to the date, Dix appears to have carved a swastika, as though he is capitulating to the new Chancellor, Adolf Hitler. But nothing is as it seems. Instead of an idealised Teutonic beauty he has painted an intensely carefree Slav. A further piece of information: the Nazis dismissed Otto Dix from his teaching position at Dresden and he spent the following years under suspicion as he painted the most beautiful and disturbing dystopian landscapes.

The ambiguous nature of reality may be why German cinema from this period is so convincing in the way it twists preconceptions. This is especially true of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis where the skeletal messenger of death waves his scythe to triumph over the destructive capitalist and his intelligent machines. This is art made in the shadow of death, by those who saw all too clearly the nature of the world in which they lived.