For those less familiar with the history of the Asia-Pacific Triennial exhibitions, it may be difficult to decipher what belongs to this, the 5th APT, and what has come before, as the latest of the Queensland Art Gallery's (QAG) now renowned triennials presents new work from thirty-seven individual artists and two multi-artist projects, from Asia, Australia and the Pacific, alongside works previously encountered in APT's since 1993 and now part of QAG's celebrated collection. Further, the old and new works are presented across both the refurbished old gallery and the impressive new Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA). As such, there is no obvious trajectory suggested but rather a fluidity of movement across the older and the new works; the older and the new gallery; established to emerging artists; and between Asia, Australia and the Pacific.

This lack of demarcation between APT5 works and others emphasises very clearly the remarkable results of QAG's ambitious and highly successful collecting practices since the first APT in 1993. The current QAG and GoMA exhibitions demonstrate the Gallery's distinctive and unmatched collection of contemporary art from Asia and the Pacific. Indeed, the Gallery rightly prides itself on its collecting focus, marking its triennial as different from other recurring international exhibitions of art. In this endeavour, many have been involved alongside the outgoing Director, Doug Hall, including former Deputy Director, Dr Caroline Turner, who was instrumental in initiating and developing the APT concept.

It's not the first time the APT has shown the works of more established artists. The fourth APT in 2002 departed from the three shows preceding it by showcasing three generations of Asian and Pacific artists, ranging from less familiar to internationally renowned. In shows from 1993 to 1999, a principal motivation was to make known the art of emerging artists from Asia and the Pacific and to bring them together under loose curatorial themes. In doing so, APT often assisted in fostering the careers of new artists, propelling them into the international limelight. In short, from the first APT to the fourth in 1999, an obvious curatorial agenda of some kind could be deduced.

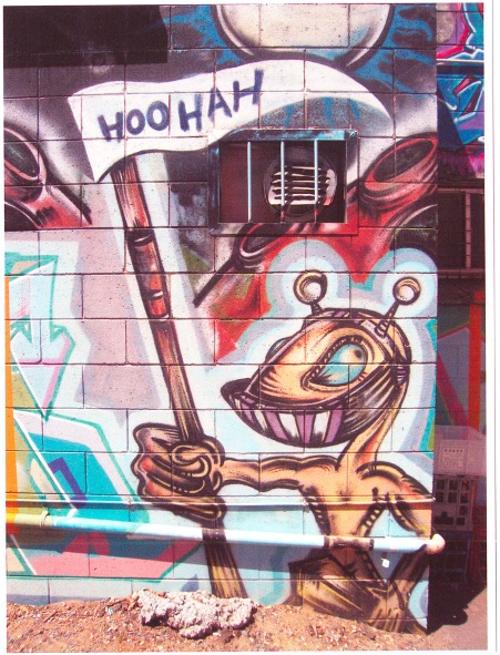

However, the 2006 APT leaves us guessing. The amazing array of works collected by the Gallery dazzles us in its magnificence and leaves us to decide which stories to take from the overall exhibition. There seems no single curatorial perspective to guide us but multiple viewpoints, which find their common basis in the artistic, social and geographic contexts of Asia, Australia, and the Pacific. Indeed, those who spend enough time between the old and the new galleries might enjoy the playful links the viewer can independently create. For instance, there is an aesthetic correspondence between the papercuts of Sangeeta Sangrasegar and those by Liu Jieqiong, and a similarity in the humour and political criticism in the cartoon-like works of Indonesian artist Eko Nugroho and Paiman of Malaysia. Such open possibilities for audience interpretation can be interpreted as a much 'safer', more audience-dependent curatorial approach than that of previous APT's.

Highlights of the exhibition include the highly visible shimmering mass hanging in the watermall of the older gallery, a boomerang-shaped chandelier by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, which not only captures the extravagance of affluent classes but also the grandeur and spectacle of most international exhibitions. Atop the watermall, another colossal and arresting sculpture is UK artist Bharti Kher's bindi-decorated elephant. While majestic and graceful, the suffering elephant also moves us to remember the frailty of life. Matching these proportions is the monumental Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong (2003) duo, in the GoMA space, by Chinese artist Wang Wenhai. These giant fibreglass figures are a monument to Mao's revered status in China, and echo the larger obsession with Mao in Chinese culture.

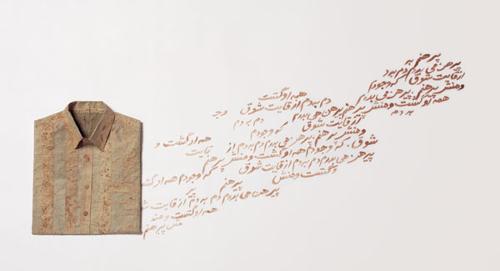

Against these larger works is the intimacy and refinement of works by Khadim Ali, Nusra Latif Qureshi and Yuken Teruya. Ali and Qureshi's separate installations present us with a series of paintings, each with intricately layered imagery, echoing miniature painting traditions. In Ali's Rustam with wings series, the paradoxes of good and evil, East and West, tradition and modernity converge by way of divergent cultural icons and artistic traditions, cupids and devils, flowers and blood. By contrast, Qureshi is emphatic in her celebration of the female heroine: bejewelled, beautiful and the sensual embodiment of love. Teruya's works also point to miniaturisation and intricacy in the artist's transformation of used paper bags into exquisite paper sculptures of trees, reminding us of the source of this discarded refuse and the relationship of consumerism to environmentalism. Above all, it is a beautifully crafted work demonstrating remarkable skill.

It was an absolute joy to see Anish Kapoor's sculptural installations, works which must be seen in the flesh for their full effect. Kapoor's marvellous plays with sculptural form, colour, space and perspective are a sight to be experienced as embodied spectators of art. Of a slightly older generation, Masami Teraoka's now well-known and much reproduced paintings, inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock painting traditions, are also a treasure to encounter directly, particularly in their foldout screen displays.

Another memorable installation is the unsettling photographic series by Justine Cooper, Saved by Science. Cooper's photographs expose us to the concealed collections of the American Museum of Natural History, bringing an eerie life to these dead objects of science, otherwise hidden in the museum's back corridors and storage spaces.

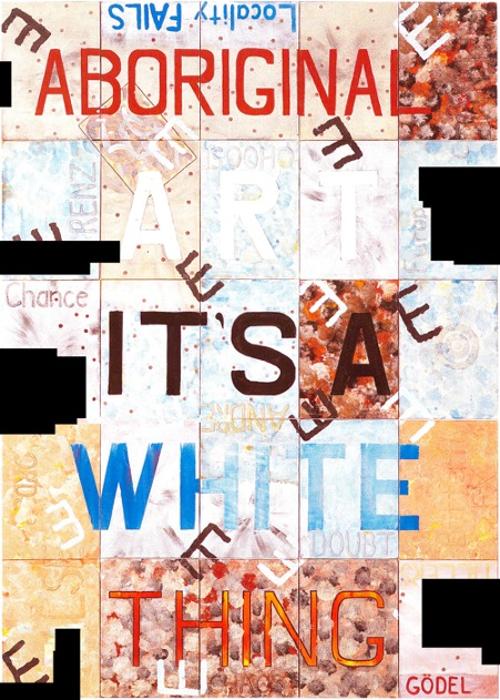

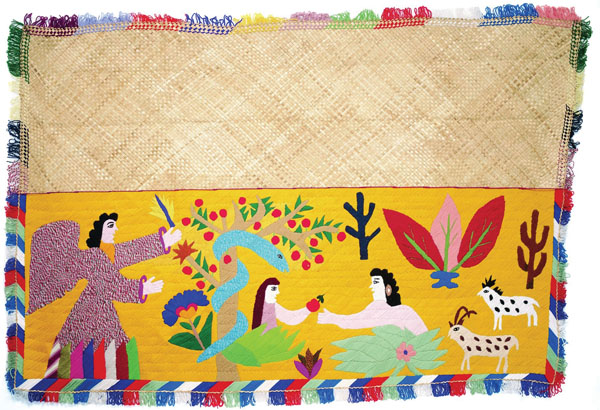

Pacific artists seemed more present in this APT. Alongside works by renowned contemporary Pacific New Zealand artists such as Michael Parekowhai, John Pule and Gordon Walters, the Pacific Textiles Project (one of two multi-artist projects, the other being the Chinese artists' Long March Project) brought together a collection of woven textiles including mats, bed covers and quilts, from various areas across the Pacific. This Project represents the APT's ongoing negotiations of what defines 'contemporary' versus 'traditional' art in Asia and the Pacific. This point is worth pondering, moreover, in relation to the naming of the new exhibition building as a Gallery of 'Modern' art, in which to house art from Asia and the Pacific beyond 1970 (interesting, given that it is usually the label of 'contemporary' that is applied to the art of this period). The addition of the historic Asian art collection in the refurbished gallery attaches another important point of orientation for reading the more contemporary collections.

The increased presence of Vietnamese art was encouraging, given its relative absence in the last few APTs. Of particular note are the installations of Dinh Q Lê – perhaps the art that moved me the most in this APT. Lê's installation Damaged Gene lured you into the gallery with its seeming cuteness and kitsch display of children's clothing; a closer inspection reveals that arms and legs are missing, echoing the dismembered and mutated bodies of child victims of war. The physical absence of the children who would otherwise wear these clothes also reminds us of these children's shortened lives. Extending this theme, Lê's Lotusland transforms the 'disfigured' forms of Siamese Twins into figures of reverence by mimicking the likeness of Hindu and Buddhist gods.

APT5 also stresses performance and cinema, marking the exhibition as a truly multi-media event. GoMA includes the new Australian Cinématèque, a home for presenting the moving image, fitted with a dedicated cinema space and media gallery. For APT5, filmic works by Jackie Chan fill the media gallery space, and six other filmmakers including Kumar Shahani and Apichatpong Weerasethakul are featured in the ongoing film program. Performances by Talvin Singh and hip-hop artists from the Pacific and Australia lured a younger, music-savvy generation to the opening events and the Children's Art Centre Initiative continues QAG's exemplary and unsurpassed dedication to children's art education.

As a long-time follower of the APT, what I enjoyed most was seeing the cumulative efforts of the Gallery and remembering all of those who have been involved in making the collection what it is today. Indeed, it is perhaps because of the APT's collecting focus and its dedication to Asia and the Pacific that the developing history of the APT has a greater reverberation with its most recent incarnation. Unlike other major international exhibitions of art, the APT has been less focused on a changing thematic from one triennial to the next, and less defined by the vision of any one curator than most other recurring international exhibitions. APT5 represents a milestone in the Gallery's history and shows the Gallery's achievement in building the best collection of contemporary art of these regions. QAG's collection has developed in the context of larger debates in art history and international exhibition practice over what defines modern and contemporary art from Asia and the Pacific and, in doing so, has faced many challenges and criticisms. For these reasons seeing the spectrum of works collected by the gallery since 1993 was a moving experience, one which caused me to reflect on how much the Gallery has grown, to recall all the artists, curators, and scholars who have made such a significant collection possible, and how much more prominent Asian and Pacific art has become in the mainstream of international art.