WORDARTORIAL

In recent years, words have arrived bigger than ever in the visual arts – projected, painted, scrawled, carved and computerised – to the point where some art is made of nothing else but language. In this issue of Artlink, sixteen writers contribute their perspectives on the multiple directions from which this verbal push has come, and the achievements of 'word as art', with special attention to Australia and the Asia-Pacific region.

As someone who maintains a literary practice and takes poetry to heart, I wanted to emphasise artists who are dealing with language as an entity with its own transformative powers, rather than as a surface (even if active, and negotiated) upon which to draw. Some artists using words don't love them as a core material, but use the unsettling effect of words to invigorate an uncertain picture with ambiguity, or to give a political slant to abstraction. Others – especially some graphic designers who don't seem to read but simply cut and paste – treat texts as so much decorative texture, rather than as a space for the mind's eye to absorb a written voice.

The art of typography treats fonts and individual letters as sensual entities to be enjoyed, looked at as well as read. Mixed in with pictures, or even becoming pictures themselves (what the American poet and critic Richard Kostelanetz calls in the context of visual poetry 'imaged words and worded images') the appearance and graphic surroundings of words can radically shift our appreciation of their sound and meaning. This floating between word and image as a verbal-visual hybridity is becoming ever more common in the world of the internet, where on highly designed web pages there is a dizzying range of pop-up windows, pull-down menus, slide-by texts, flashing buttons and multiple options of where to click next. New phones such as the recently announced iPhone from Macintosh will offer not only the voice we expect (mobile phones, like internet access, were uncommon in Australia before 1997) and a camera for photography and video, but a screen keyboard for writing emails and accessing the web, all packed into a device small enough to go into a jeans pocket. 'Texting' on the phone and email messages are the new way of sending letters, but unlike posted letters, which have a physical presence and can be preserved, the new media tend to the instantaneous where disappearance is the norm. All of these forms of personal and public media are constantly being exploited and expanded by artists, and another issue of Artlink is needed to show current trends and achievements.[1]

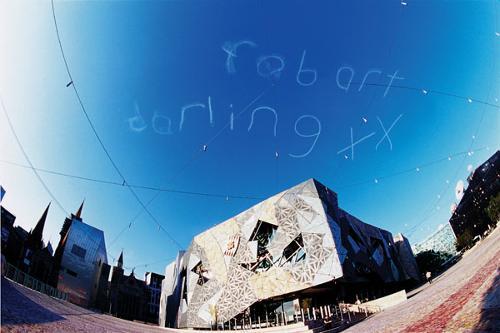

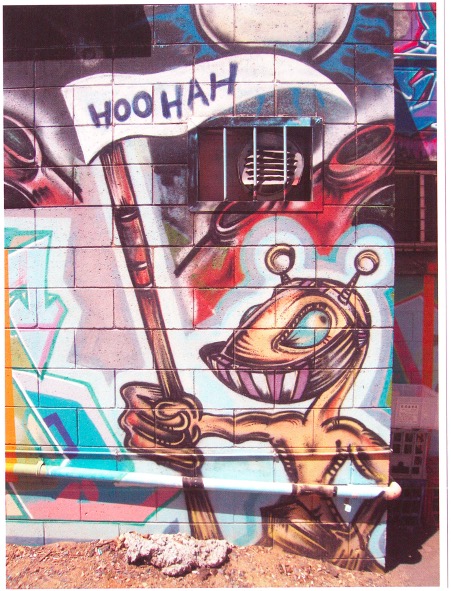

Meanwhile, graffiti is a 'curse' requiring constant vigilance and clean-up budgets from local councils where I live, while Melbourne has become a spraycan capital of 'stencil art' (as celebrated in a recent television documentary) where ways have been found to incorporate these disruptive edges of street style into the cityscape.

As British artist Banky wrote in the Guardian newspaper, predicting a soulless clean-up of London as it prepares for the 2012 Olympic Games: 'Melbourne's graffiti scene is a key factor in its status as the continent's hothouse of creativity and wilful individualism. Witty, playful, often angry, the free rein taken by Melbourne's street artists became about much more than just daubing on a wall. It has drawn in generations of artists, thinkers and tourists to explore and experiment in the city. It gave fresh life to the worlds of fashion and music and is arguably Australia's most significant contribution to the arts since they stole all the Aborigines' pencils.'[2]

Writing is a physical act and its antecedents began long ago with drawing and painting on cave walls, and with inscribing marks into rocks. Some of the oldest cave art is in Australia, with Aboriginal people inhabiting the south of Australia by 46,000 years ago, while the earliest known remains of modern humans in Europe are only about 35,000 years old.[3] Recent discoveries about the migrations of homo sapiens into the Asia-Pacific area, made through mitochrondrial DNA mapping and the excavation of ancient sites, show that 'we' (as Homo Sapiens) have used both our technologies and our social ingenuity to make the human world, and our tongues to explain it. If the drawing and marks preserved on cave walls aren't written words, they are certainly prototypes for words. Just as hunter-gatherers must 'read' the land, they 'wrote' the symbolic presences of their habitat into their shelters and communal places.

The development of written language as an alphabet (by the ancient Phoenicians, for example, more than 5000 years ago) represented a repeatable structure for the spoken word. Writing lost its pictorial qualities since the alphabet was not visually representational but phonetic, based upon the sounds whose combination makes speech possible. Writing systems evolved independently in different places and periods, including Egypt, China and South America, with various combinations of the pictographic (where the smallest units look like something in the world) and the phonological or phonetic (where the smallest units stand for consonants and vowels). The visual dimensions of writing were suppressed in favour of a standardised form where words flow from the page through the eye as mere code, opening up in the reader's inner ear as speech. Plato was suspicious of the alphabet as a relatively new and dangerous invention (in the fifth century BC) which lessened memory and encouraged deception; and also belittled visual representations as faint or unreal semblances. In the medieval developments of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, God being invisible was judged to communicate not through images but through divine spoken language, making the written word pre-eminent. Painting and drawing increasingly represented the world of appearances, not philosophy. This was only reinforced by the technologies of printing using moveable type.

During the Enlightenment, a distinction was drawn between the literary arts, which were 'centrally involved with narrative because they unfolded in time, where the visual arts proper domain was deemed to be space, and so could not be said to owe anything to verbal language'.[4] The appreciation of painting and sculpture was deemed to involve the sensual entity of taste rather than the conceptual basis of written language. This logic is at the heart of Clement Greenberg's promotion of painting as a purely optical experience, whose essential quality is its flatness. Text has no place in a painting in this view, except as another kind of surface. It has taken the studied re-appreciation of earlier movements such as Dada to see how one of the important roles of advanced art over the past hundred and a bit years has been to bridge the divides of word and image and create fresh amalgams of the mind's work with speech and hands, expressing the whole body. The artists and writers associated with Dada produced not only art objects but performances, installations, films and posters, as well as publications with radically new approaches to the printed page as a vehicle for the dynamic interplay of typography, graphics and photography.

When Duchamp attached a bicycle wheel to a stool for his own study and amusement, that spoked wheel was new technology – but his interest was in kinetics: the shock this 'readymade' caused was almost incidental to his purposes. I remember a story of him walking through the huge displays of a Paris Airshow with the sculptor Constantin Brancusi and pointing to the curved blade of a large wooden propellor, saying (in French, of course): 'Beat that!' It can be argued that Duchamp was essentially a writer, as well as a painter and sculptor, as were many of the Dadaists and Surrealists. Much of their international connections and reputation was built from their publications, which treated the page as a canvas, or a sheet of sensitised photographic paper ready for multiple exposure (think of Man Ray's experiments).

One kick-off for these new approaches to the printed page had been made by Stephane Mallarmé in 1897 with his typographically radical book whose title can translate as 'A Dice Throw will Never Do Away with Chance' (see Noreen Grahame's essay in this issue. This influenced the Australian poet Christopher Brennan to write and hand-design his 'Prose-Verse-Poster-Algebraic-Symbolico-Riddle Musicopoematographoscope' in the same year, which similarly stretched the sizes and kinds of type on large pages for its effects.[5]

When Picasso and Braque included scraps of printed paper in their 'Cubist' paintings, was it merely as signs pointing to other kinds of flat surface, or were they echoing the ever-increasing intrusions of commercial culture into daily life, and responding to the literary fascinations of their poet friends? How seriously did they plan the effects of these words in their overall compositions? Kurt Schwitters was not only the maker of collages which 'spoke' through fragments of text glued in among the detritus of his cut and torn paper scraps, but a sound poet who could boom out his abstract poems of exquisitely gutteral gobbledegook so loudly that he was reputed to break wine glasses.

When the American 'projectivist' poet Charles Olson wrote in the 1950s: '

And words, words, words / all over

everything – no eyes or ears left

to do their own doings – all invaded,

appropriated, outraged

even the mind/that worker on what is [6]

he was responding (my guess) to the escalating volume of language thrust through advertising into the urban world of get-ahead capitalism as America kicked up into global mode after the long slog of WW2. In the clamour for the attention of consumers, there was a jostling competition of slogans, logos, trade symbols, radio jingles, sing-a-long pop lyrics, television chatter and wooing texts which increasingly infiltrated personal space and time. This entry of the spoken into the visual world through public print display and broadcast media wasn't new – the impact of advertising on city billboards which began in the late nineteenth century had soon been reflected in art – but it was bigger, brasher and more prominent than ever before. Pop Art's answer, reacting in part against the wordless, expressive gestures of Abstract Expressionism, was to celebrate and/or critique (a longer argument) the impact of these new commercial energies, which included words – lots of them.

Alex Selenitsch has compressed years of reading into his article 'WORDS words WORDS' to draw some definitional boundaries around the very different approaches to the use of language taken by movements broadly labelled as Concrete Art, Conceptual Art, Minimalism and Pop Art among others.

Australian artists have always been quick to respond to international tendencies, and to make original works which are not derivative but speak independently. Allan Riddell's concrete poems exhibited as screenprints at Gallery A in Sydney[7] in 1969 were brilliant extensions built from his close engagement with Ian Hamilton Finlay's early poster poems of the mid 1960s. In the early 1980s when the Gallery was closing down, Alan Riddell having died in Scotland, the remains of the prints were for sale relatively cheaply, although each still cost at least a week's rent of a Bondi apartment. Luckily Ruth and Marvin Sackner were in Sydney from Miami that week (the only time they have visited Australia) and bought a complete set for their vast collection, the Sackner Archive of Visual Concrete Poetry, which is the pre-eminent repository of all word-image experiments. As far as I know, the remaining prints were lost. See their informative website: www.rediscov.com/sackner.htm:

I like to think that Rosalie Gascoigne had looked similarly closely at the fractured letterforms published as visual poetry by the Italian poet Adriano Spatola in the 1970s and 1980s, since there are strong resemblances in their gestural graphics. Visiting Adriano Spatola near Pisa in 1984, he showed me an original copy of For the Voice (1923) by El Lissitsky and Vladimir Mayakovsky, which brought Constructivist graphics and poetry together in an indexed book. When he offered it for a hundred American dollars, why couldn't I find the money? How good to be able to finger the pages of a book as it was meant to be experienced instead of looking at it through a glass cabinet, shyly opened on a single part of its depths. This issue always bothers the curators of artist book exhibitions: how do you let the visitors participate in the physicality of the book, when it is rare and fragile? Thus the glass cases and, sometimes, supervised access with white gloves. The best hope here is a private gallery, where as a potential buyer you may be invited to play with a book's dynamic structure.[8]

The Fluxus movement of the 1960s and 1970s is discussed by Anne Kirker and Noreen Grahame, who both show how this international grouping of like-minded participants retains its cheerfully disruptive influence with what Fluxist member Ken Friedman calls its 'serious concern with insignificance'. The deliberately ephemeral and multiple nature of much Fluxus work (both in performance and publication) might have been meant as the opposite of deliberately collectable, 'expensive' art like painting, but soon enough the original Fluxus works became unaffordable even to collectors like the Sackners. This led them to their wider ideas, of collecting word-image interactions beyond the obvious categories of 'movements'.

The 'missing forms'[9] in critical assessments of word-art relationships have often been the extensive explorations of concrete and visual poetry, because much of it has appeared on pages not designed to have impact on gallery walls.

An important survey was 'Visual Poetics: concrete poetry and its contexts', curated by Nicholas Zurbrugg[10] in 1989 for the now closed Museum of Contemporary Art in Brisbane. The catalogue essay explains that:

'The 'concrete poetry' movement (along with its precursors and its 'post-concrete phases), is particularly interesting as one of the first truly international avant-garde movements. Whereas Futurism, Surrealism and Expressionism were all centred in particular cities, concrete poetry flourished on a world-wide scale. (&) Rather than existing 'between' poetry and painting, new forms of verbal/visual creativity appear to occupy and identify creative spaces 'beyond' poetry and painting, as word, image, graphics and colour combine with typography, paint, photograph, photocopy and computer.'

There is a large discrepancy between the cost of book-page works and those made for wall display (an indicator of the gap between literary and visual interests as cultural place-getters, emphasising display). A medium-sized screenprint by an artist such as Ian Hamilton Finlay can be fifty times as expensive as a more interesting small book by the same artist also made in an edition of two to three hundred, and similarly unsigned. Finlay's death in 2006 at the age of eighty was a great loss to complexity and he is sirely mossed, to post a respectful spoonerism in his honour.[11]

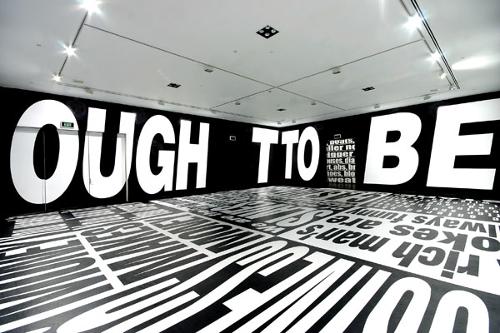

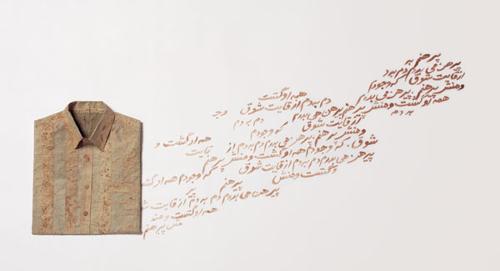

Prominent international artists who make words their core visual material have been exhibited in Australia and the region over the past decades. These include Ed Ruscha, Lawrence Weiner, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Bruce Nauman, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. Other well known artists who use language interestingly in some aspects of their work, such as Andy Warhol, Hans Haacke, Richard Prince, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Tracey Emin, Shirin Neshat, Kay Rosen, Tom Phillips and Bill Seaman have also been represented to varying extents. This listing is seriously incomplete, and is meant simply as an indication of the range of practices which might be included in a 'word as art' show.

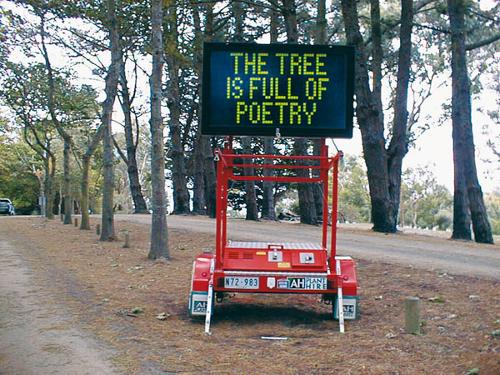

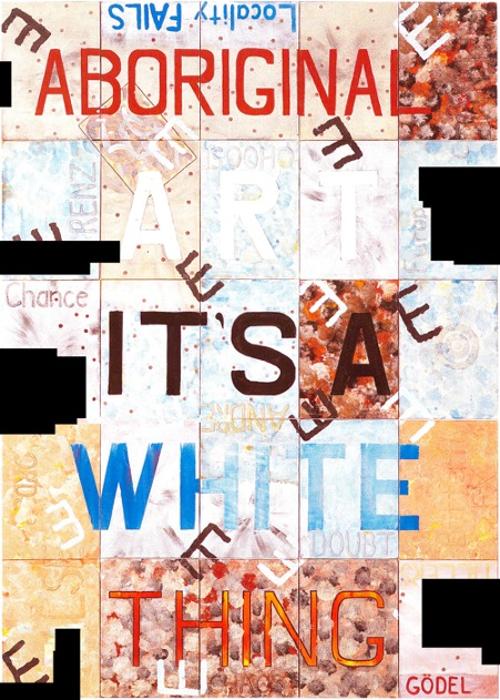

In my dream exhibition the artworks all speak for themselves, playing between visual dynamics and their physical embodiments of the written tongue. The words dance in and out of earshot, each letter becoming a sensual figure, aware of its movement in typographic space. In some works, there is nothing but letters (think of Scott Redford's large chromed steel sculpture made of the letters R O C K stacked up vertically, or Mikala Dwyer's large free-standing perspex letters 'IOU' with their cool designer presence, or one of Rosalie Gascoigne's fractured letter 'landscapes' made of sliced up reflective yellow road signs, or Robert MacPherson's pleasure in vernacular roadside food stall announcements); in others, the presence of a single word or a phrase completely alters our response to a painting (think of Ian Burns' conceptual questionings, written across unsuspecting scenes, or Jenny Watson's shy diary notes with her figures and horses). Words form a significant part of some artists' wider practice (think of Aleks Danko's homilies on painted or printed posters, or Fiona Hall's delicate metal alphabet with each letter shaped as robust nudes, or Imants Tillers' layered language complicating the pictures) but are not their primary concern. Some artists make painterly compositions of dictionary definitions (think of Bea Maddock) or literary quotations (think of Angela Brennan's cheerfully coloured text paintings[12]), while others celebrate the idiosyncracies of pop culture. Cartoonist Michael Leunig uses drawings of the public sign (especially the billboard, or roadway notices) with new texts to declare his poignant ironies, while Jeffrey Smart paints them plain (especially shipping container logos and road direction arrows) as a kind of abstracted voice of authority in his industrial landscapes.

Noting these artists is just a sample of the many prominent and emerging artists who should or could be included in this special issue of Artlink, if it was a full critical survey of 'word as art' in the Australian and Asia-Pacific region rather than (as it is) a fresh and selective view generated by the writers who were able to contribute. My deep appreciation goes to all of them.

>For an extensive history of concrete visual (and sound) poetry, see www.ubu.com

> For an invaluable source of information and opinion on international artists' books, mail art, email art, rubber stamp art, and so much more, see Judith Hoffberg's Umbrella Online at www. umbrellaedrtions.com

> The key academic body is the International Association of Word and Image Studies and their affiliated magazine Word and Image. The next IAWIS conference is in Paris in September 2008. See www. iawis.org

Relevant exhibitions include:

Words on Walls.- a survey of contemporary visual poetry, curated by Barry Reid, Heide Art Gallery (now Heide MoMA), Melbourne 1989 (catalogue published)

The Palimpsest.- between image and text between text and image, co-curated by Ruark Lewis and Jacqueline Rose, Goethe lnstitut, Sydney, 1996 (catalogue published)

Word.- artists explore the power of the single word, curated by Linda Michael with Peter Tyndall, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney 1999 (catalogue published).

Unscripted.- language in contemporary art, curated by Wayne Tunnicliffe, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2005. The curator's essay 'Write Now.- when images are not enough' appeared in the Gallery's magazine Look, May 2005, pp24-26

Footnotes

- ^ See e.g. Mary E. Hocks and Michelle R. Kenrick (eds) Eloquent Images: word and image in the age of new media The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2005.

- ^ See 'The Writing on the Wall', Guardian 24 March 2006, on-line at: http.-1/arts.guardian.co.uk/ features/ story/ o,, 17 3 84 5 3, o o. htmI

- ^ Earth's first beachcombers ended up in Australia, by Deborah Smith, Science Editor, Sydney Morning Herald, May 2005.

- ^ Writing on the Wall.- word and image in modern art, Simon Morley, Thames and Hudson, London 2003, pages 13, 16-17- Simryn Gill and Jeffrey Shaw are the only Australian artists mentioned in this extensive study. For a detailed overview of the history of writing, see. The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Language, David Crystal, Cambridge University Press 1987, pp198-203.

- ^ Musicopoematographoscopes, facsimile edition, with an introduction by Alex Clark, Hale and lremonger, Sydney, 1981.

- ^ Charles Olson, from The Maximus Poems (quoted from memory).

- ^ Published later in Eclipse.- concrete poems 1963-1971 by Allan Riddell, Calder and Boyars, London, 1972.

- ^ See e.g. Grahame Galleries and Editions, Brisbane.

- ^ Missing Form.- concrete, visual and experimental poems, Collective Effort Press, Melbourne 1981.

- ^ Nicholas Zurbrugg (1947 to 2001) was 'an energetic advocate of postmodern expression', to quote from his obituary in The Guardian, untiringly investigated and promoted key issues and practitioners in the field of verbal-visual interchange. He is greatly missed by friends and colleagues in Australia.

- ^ Ian Hamilton Finlay's available works can be found for sale through his own Wild Hawthorn Press, at ianhamiltonfinlay.com See also the brilliant poetic art publications of his son Alec Finlay's Evening Star Press at www.alecfinlay.com/bookshop.html

- ^ See Heat magazine 10, New Series, 2005, for a suite of Angela Brennan's text paintings.